or,

The Fallacy at the Heart of Modern Physics

Let’s begin with the basic physics behind time travel. Not the science fiction version — with its paradoxes and plot twists. And not the mathematical physics version either — where general relativity admits closed timelike curves, or special relativity allows faster-than-light observers to loop back into their own pasts.

This isn’t about exotic hypotheticals or metaphysical speculation — not the details of how time travel might happen, or what strange consequences would follow if it did.

I want to focus on something more foundational: The core structure — topological, dimensional, and dynamical — that a world must have for time travel to even make sense, physically.

What do we have to assume before we can even ask whether time travel is possible?

That’s where things get interesting. Because the very idea of time travel rests on something most people — including physicists — never notice: A subtle but devastating category mistake.

One that’s gone unacknowledged not just in pop science, but in physics and philosophy.

It happens when we treat occurrences in time — things that happen — as if they were existents in space — things that are.

It happens when we first spatialize time — treating it as one of four dimensions of space-time — and then, almost automatically, tacitly, temporalize the entire manifold.

We begin thinking of space-time itself as an existent object, quietly assigning it the same ontological status we intuitively give to space.

But that interpretive shift comes with baggage: We have, without even realising it, added another dimension — a second time — like Newton’s absolute time, ticking behind the scenes.

We start thinking of space-time like Newtonian space: An arena in which everything exists, evolving as events happen.

And that tacit assumption — that the four-dimensional manifold exists just like Newton’s three-dimensional space did — quietly smuggles a fifth dimension into the model: a dimension not present in the formal physics, but required to make our mental picture feel complete.

This slippage doesn’t change the mathematics. It doesn’t break the physics. But it distorts our interpretation. And once you notice it, the whole conceptual scaffolding starts to wobble.

You begin to see that the very idea of space-time — one of the most profound and seductive consequences of Einstein’s relativity — has been fundamentally misunderstood.

That we’ve been misreading what the formal theory actually tells us about the structure of reality.

This problem is everywhere. It cuts across physics, philosophy, popular science, and science fiction alike.

And it all starts with collapsing the categorical difference between what it means for something to occur, and what it means for something to exist.

There is a fallacy at the heart of modern physics.

In this essay, I’ll use the familiar time travel trope to unpack it — to show that there’s a gap between what the formal theory says, and how we’ve come to understand it. And to argue that what we think relativity tells us about the basic structure of reality — the ontology we think it implies — cannot, even in principle, be what we’ve imagined it to be.

What We See Is Not What Is

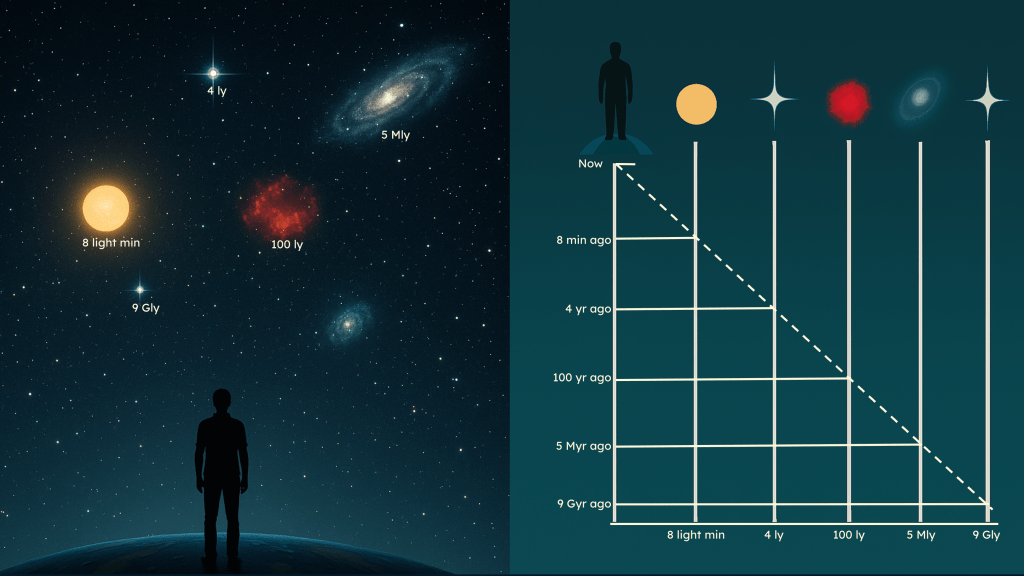

We’ll start by clarifying something fundamental: What we see is not what is.

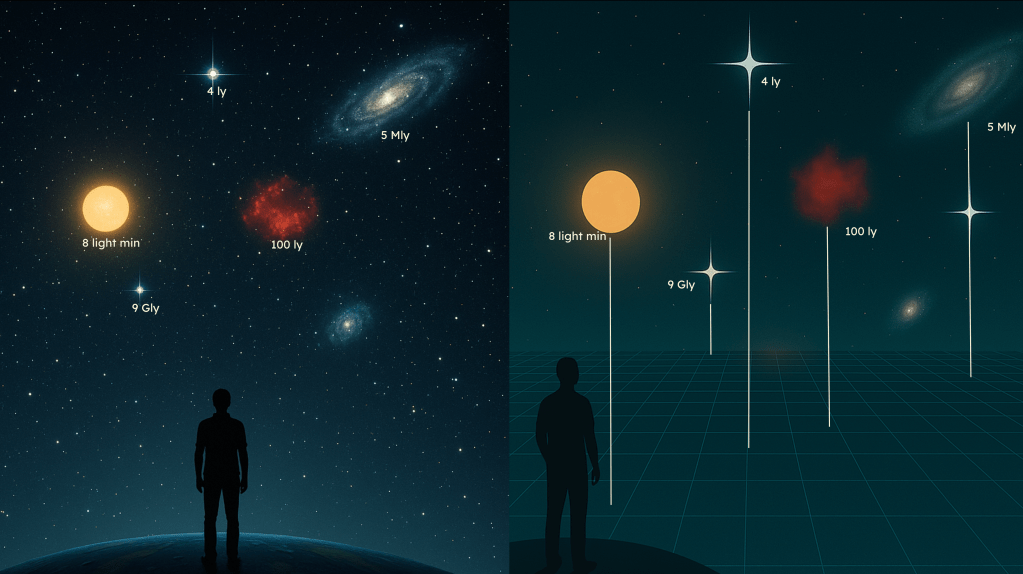

We don’t see the world as it is right now. We see light — photons — that have traveled from distant things. Those photons reach our eyes only after a delay, after journeying through space over time. And those photons aren’t the things themselves — they form images of those distant objects.

So we don’t witness the things themselves. And we don’t see them in their present state. We see only images from the past — projections of what they were like when the light left them.

And the world has evolved since then. Everything has changed.

What we’re really interacting with, moment by moment, are fragmentary representations of the past.

Still, we don’t live as if that’s true. We think of the world as existing now — all around us, in the present. A three-dimensional world, coexisting with us as time progresses.

In cosmology, we describe a whole universe that exists now, filled with galaxies of stars and dust that formed and evolved over 13.8 billion years since the Big Bang.

In our own galactic neighbourhood, we imagine that the Solar System exists now — even though there’s always a lag between the time of what we see and the time of what is. When we look at Venus, we know we’re seeing light that bounced off its clouds a little over two minutes ago. When we observe Pluto, we’re seeing photons that set out more than five hours earlier.

And yet, we still infer — intuitively and tacitly — that these are things that exist now, within a Solar System — a Galaxy — a Universe — that exists now.

Even here on Earth, where light travel times are just fractions of a second, it’s still possible to pause, look around, and recognize:

What we see is not what is. What we see is a projection from the past — of what now is.

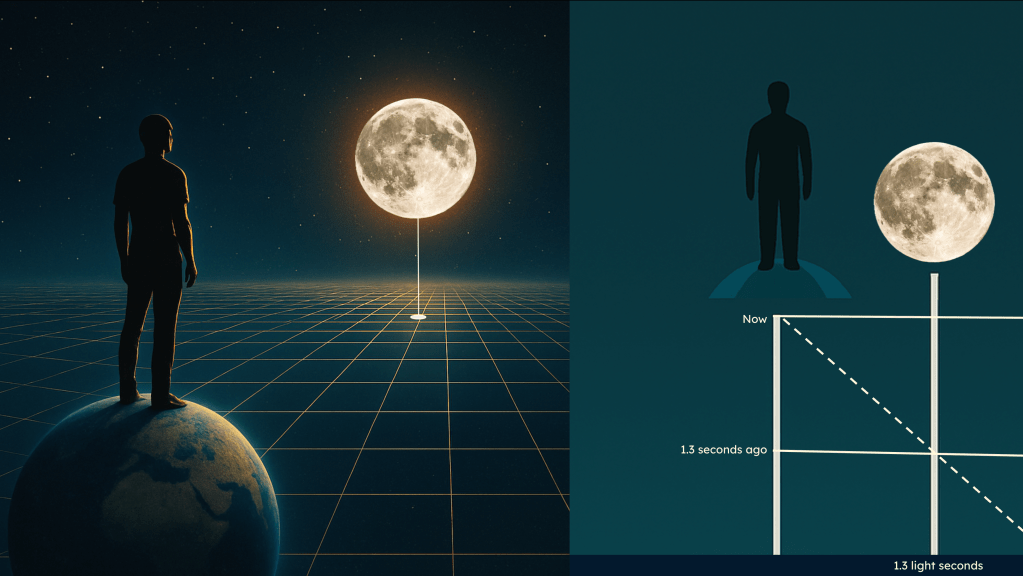

Just recall the last time you looked up at the Moon. It’s about 1.3 light seconds away. That means, as you stared at it, your eyes were receiving photons that left its surface 1.3 seconds earlier. Sunlight had reflected off the Moon, bounced into space, and finally reached your eyes.

So even as you watched it hover in the sky, you weren’t seeing the Moon as it is now — you were seeing an image it projected into space — a kind of video, streaming from the past.

And still — even knowing this distinction — our intuition tells us the Moon exists now.

It’s from this everyday intuition — this picture of the world as existing now, in three dimensions — that we’ll begin, as we try to clarify the physical structure required for time travel to even be a coherent possibility.

Relativity, of course, complicates this picture. But we’ll leave that complication aside for now — not to avoid it, but to address something even more fundamental first. Because while the relativity of “now” is a genuine philosophical and physical challenge, it cannot be properly appreciated until we’ve resolved a deeper confusion: the difference between what exists and what occurs — and the ontological collapse that happens when we describe occurrences, or sets of occurrences, as if they exist.

Only after we’ve clarified this distinction — and worked through its implications for any supposed existence of space-time — will we be ready to confront the interpretive problem that the relativity of simultaneity actually presents.

So for now, we’ll proceed by grounding the problem in familiar, intuitive concepts — and use those to reveal the structural foundations that must be in place for time travel to even make sense in the first place.

Existence vs Occurrence

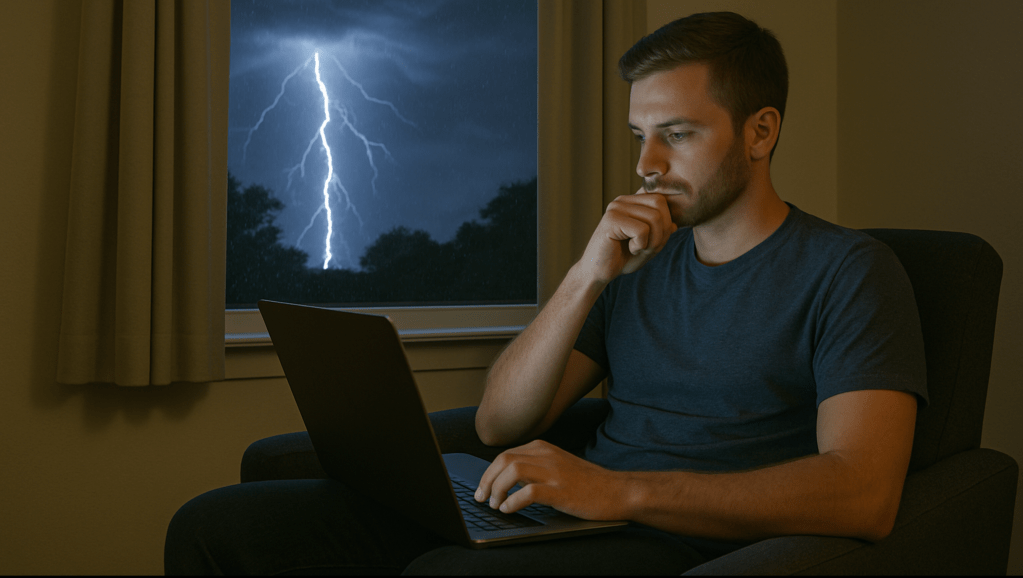

There is a significant physical difference between something that exists — like the chair you’re sitting on — and something that merely happens — like a lightning bolt, or the flash of a camera.

Both can be described as three-dimensional. But only one persists through time. The other is over as soon as it begins.

To put this more precisely: a three-dimensional thing that exists must have some nonzero duration. It endures — even if only briefly. It persists — not as a moment, but as an object. It is, for some span of time.

By contrast, a three-dimensional thing that merely occurs is atemporal in structure. It happens in an instant — a flash, a blip, a pure event.

In essence: occurrences happen as things exist.

An example helps bring this more clearly into focus. Imagine the Sun. It’s about eight light-minutes away. So when you look up, you’re not seeing the Sun as it is now — you’re seeing an ever-evolving image of it with an eight-minute lag. The Sun right now — as it exists — is something different.

Now imagine something else. Picture an elephant next to the Sun. And imagine that this elephant flashes into existence for one precise instant, and then vanishes — a zero-duration, three-dimensional event.

In that moment, the elephant has no endurance. It does not persist. It does not exist in the full sense — it occurs.

And that’s the key point: the elephant occurs; the Sun exists.

We’re not talking about metaphor or perception here — we’re talking about ontology: the structure of what is.

There is a deep, structural difference between objects that exist (or persist, or endure), and events that merely occur (or happen, or transpire). They belong to different ontological categories.

An object may exist for a century; an event happens at an instant. These are not interchangeable. This sentence becomes incoherent when “object” and “event”’ are swapped.

And confusion arises when we collapse that distinction — when we treat occurrences as if they exist, or speak of existents as if they merely occur.

That confusion, as we’ll see, underwrites many of the most seductive — and mistaken — ideas in modern physics.

Space-Time: The Real Elephant in the Room

Now that we’ve clarified the difference between occurrences and existents, we’re ready to take a clearer look at space-time itself — and to revisit what relativity has actually been trying to tell us.

The idea that time is somehow “like space” is deeply embedded in modern physics. In fact, relativity encourages us to think of time as spatialized— as one dimension in a four-dimensional manifold, where space and time are woven together into a unified entity: space-time.

But this shift in framing doesn’t derail the distinctions we’ve just established. The conceptual tools we’ve laid out — especially the ontological difference between things that exist, and things that merely occur — are entirely compatible with relativity. They allow us to interpret the structure of space-time more clearly—without smuggling in hidden assumptions.

We’re not going to take on the relativity of simultaneity just yet. That’s a complex topic, and it deserves its own focused treatment (which I’ve done in this essay). For now, we’re still laying the foundation: exposing the category error that arises when we reify events as existents, and clarifying the basic topological structure underlying time travel narratives — and the way many physicists think about space-time itself.

So let’s take a step back from our intuitive picture of persistent, three-dimensional objects, and ask a basic question: what does the term “space-time” actually mean?

In standard physics, space-time is simply defined as the set of all events that ever occur in the universe.

And most of these events aren’t dramatic. They’re not someone’s birth, or death, or even one of the quieter moments along their life’s timeline — like sleeping, or daydreaming. Most events in space-time are totally innocuous. They’re things like a tick of the clock at some lonely point in space, a million light-years from Earth — one that’s synchronized with five minutes from now in your current frame of reference.

Such an event may never be observable, and there may be nothing of interest occurring there and then. But that location in space and time still occurs. And that’s what we call an “event.”

That’s what the overwhelming majority of events in space-time are like. Still, the definition includes the more memorable ones too — like the assassination of Julius Caesar, the impact that wiped out the dinosaurs, the moment of your birth.

Taken together, space-time is the set of all such events: every instant that occurs, at every point in space, throughout all of time.

This is not controversial. It’s textbook physics.

But it raises a deeper question: Does it actually make sense to ask whether space-time exists? or whether any particular event in space-time exists?

Think back to the elephant we imagined — the one that flashed into and out of existence beside the Sun. Now consider just one atom in that elephant’s three-dimensional body. Just one spatial location, at the instant when the elephant occurred. That atom is what we would call an event. And if it’s an event, then it happened. It occurred.

So can we say that it exists?

No. We’ve already established that occurrences are not the same as existents. They lack duration. They do not persist. And existence — in the full physical sense — always implies a span of time.

Things do not exist atemporally. The very notion is oxymoronic.

So, can we then say that space-time itself “exists”?

Sure — we can say that. But if we do, we’re not just describing the four-dimensional structure. We’re adding something. We’re adding another dimension — one that isn’t captured within the four dimensions of space-time. A fifth dimension that captures the sense that space-time itself exists— in the same way that we intuitively understand ourselves and all the three-dimensional objects around us to exist.

And when we smuggle in this fifth dimension, we cross a significant threshold — not into higher mathematics, but into a metaphysical model where space-time isn’t just the set of all that occurs, but a structure that is.

A structure that exists — with a sense of duration that isn’t contained within its internal time-dimension.

And that move — quietly and without acknowledgment — transforms four-dimensional physics into five-dimensional metaphysics.

Existence as a Physical Dimension

When I say that existence is a physical dimension, I don’t mean it’s like space — a direction you can point toward, or move through.

I mean something more precise. Something more foundational.

I mean that existence is a structural feature of reality. It varies independently of space. And it gives form to persistence.

It’s not a feature of things that happen. It is the condition that allows them to happen at all.

Let’s break that down.

Remember our elephant? The one that flashed into being next to the Sun — fully formed, three-dimensional — and vanished in the same instant?

That elephant was a flash. An event. It occurred.

But it didn’t exist — we’ve established that.

There was no persistence to it. No duration. You couldn’t walk around it. You couldn’t study it. You couldn’t even say that it was — only that it happened. Just once.

Now, you might be tempted to ask: “Didn’t the elephant exist — at the moment it happened?”

But that question has already been answered.

To ask it is to forget what we’ve just established — that existence requires persistence. That to exist is to endure. And that occurring at a moment is not the same as being at that moment.

So no — the elephant didn’t exist at that moment. It occurred.

And rephrasing it as an existent isn’t just a linguistic slip. It’s the category error in action — smuggling persistence into what was only a flash.

Now imagine another elephant — but this time, one that doesn’t vanish.

This one is in the room with you. Breathing. Standing still. Present.

You could walk around it. You could touch it. You could hear it. You could be afraid of it — because it’s an elephant.

This elephant doesn’t just occur. It exists. It’s there, with you, as time passes.

So what changed?

Not its shape. Not its mass. Not even its position — it’s standing still.

What changed is that this elephant endures. It’s present with you for more than an instant. You can say when it arrived. You can say when it left. You can measure how long it was there.

And that’s the key. That’s what I mean when I say that existence is a physical dimension.

Not a direction. Not a line. Not something that flows or unfolds. Not something you move along or through. But something that can be measured — something that spans time.

Existence is what the clock measures.

This isn’t abstract. This is a fundamental characteristic of the world you live in.

You don’t experience your own being as a single flash. You don’t just happen — every moment of your life, all of them occurring at once — and then vanish.

You endure. You live, temporally. Moment by moment.

Not because you’re “moving through” time — as if sliding along some invisible track that’s already laid out prior to your existence along it — to imagine that is to imagine the dimension of existence itself as existing prior to the unfolding of your existence.

Say that ten time, fast. That line of thinking (and speaking) is a complete mess.

No: you endure not because you’re “moving through” time, but because you possess the ontological condition of existence.

You’re an existent thing.

And that’s what existing things do. They persist. They endure. They are.

And that’s only possible because time is a dimension — and existence is the physical structure that time reveals.

But here’s the part we often miss: We don’t just use time to describe change. We use it to describe persistence — the endurance of real things across moments that are not the same.

That’s what clocks measure: not movement through space-time, but being that lasts — and as it does, each tick of that clock becomes a new event; a new happening.

So: when we describe that lasting — when we chart the unfolding of real events within a temporally structured world — we construct something.

A map. A geometry. A scaffold for everything that happens as the world exists.

That scaffold is what we call space-time.

But space-time doesn’t exist. It doesn’t persist — not as reality, anyway.

It doesn’t endure like the elephant in the room, or the person you love, or the world you inhabit.

It is the coordinate structure — the geometry — a way of representing, at once, all that occurs as those things exist.

And to treat space-time itself as if it exists — as if the four-dimensional block is — is to add something. It’s to sneak in an extra layer — one that gives persistence not to the real world, but to the map we use to chart the events that unfold as it persists.

That’s the final move. The hidden shift. The step where physics ends and metaphysics begins.

Because the moment you treat space-time as something that exists — with duration, with presence, with ontological weight — you’ve invoked a fifth dimension.

Not a new axis to flow through. Not a higher-dimensional space. But a structural layer that confers being upon this map of occurrences.

And that’s not an insight hidden in the mathematics. It’s a mistake hidden in the grammar. A category error so subtle, we built a century of physics on top of it without noticing the sleight of hand.

Until now.

Meta-Now

The idea that space-time exists quietly invites us — often without our noticing — to treat all events across time as somehow… present.

Philosophers ask: “Does Julius Caesar’s death exist now?”

But what exactly does now mean in that sentence?

It doesn’t mean “simultaneous with us.” Not physically. Not relativistically. There’s no frame in which Caesar’s death is simultaneous with anything happening here, today — on Earth.

It’s deep in our past light cone. It’s an event that already happened. And it can’t be now — in any physically meaningful sense.

And yet — if time travel is supposed to be real — if it’s possible to visit that moment — then the moment must still be there in some metaphysical sense — waiting, somehow, to be arrived at.

That’s the rub. That idea only makes sense if we believe the event still exists now — that then can be gone to. Not just that it occurred — but that it persists.

But here’s the problem. That sense of now — a now that applies equally to all events across time — across space-time — is not physical. It’s not relativistic. It’s not in the equations.

It’s second-order.

A kind of meta-now layered over the entire space-time manifold — as if all of it, from the beginning to the end of eternity, were sitting there presently — a set of events that could all be gone to, if only a time machine could be built.

It’s the now of a Newtonian time-dimension — the one we imagine when claiming that space-time exists.

Not just as a map of what occurred — but as a thing that always is.

That’s the move. That’s what the reification of space-time smuggles in. It doesn’t just chart events. It turns the map itself into a thing — a thing with its own sense of now that applies to eternity — all at once.

And that idea — the idea that space-time itself persists, with all eternity “presently enduring” — not only requires a fifth dimension — but gives that dimension metrical structure.

A hidden axis in which the whole four-dimensional block remains ever-present, ever-enduring, in the same way we tacitly imagine the three-dimensional world around us to endure.

An absolute meta-time dimension, like the time dimension of Newtonian physics, but in this case applied to all eternity — all of space-time.

But that fifth dimension is not in the physics. It’s in our heads. In the way we casually — tacitly — imagine things to be when we think that they are.

The very idea that space-time exists — which is everywhere in physics discourse — is the result of a tacit levelling up of the dimensionality of reality as expressed in Newtonian physics. In place of a three-dimensional space that exists as absolute time progresses everywhere, uniformly, we imagine a four-dimensional space-time that exists as absolute meta-time progresses everywhere, uniformly — flowing “equably without relation to anything external.”

The Basic Physical Structure of Time Travel

Imagine a version of space-time like the one in Back to the Future, or Avengers: Endgame, or Doctor Who, or Harry Potter — a world where time travel is possible, and specific events can be revisited, sometimes with drastic consequences.

This is the world of the grandfather paradox: What if you go back in time and kill your grandfather before your father is conceived?

Then your father never exists. You’re never born. So… how could you have gone back to kill your grandfather?

This is the core puzzle at the heart of Back to the Future, where Marty McFly’s very existence begins to unravel after he accidentally interferes with his parents’ first meeting.

What, exactly, is supposed to stop him from vanishing completely?

It’s a paradox we easily picture once we accept the hidden assumption behind most time travel stories: that the entirety of space-time exists, and can — at least in principle — be traversed.

That’s the trick. These stories don’t just describe what happens. They picture space-time as a persistent structure — a four-dimensional world through which beings can somehow move, reappearing at different space-time events from which their consciousness continues once more to flow in the way that we’re accustomed to.

You can imagine such worlds like a riverbed, with awareness flowing through it like water. Or imagine the whole river at once, and the flow becomes just a glint of light shimmering along a fixed current — each moment a tiny flicker within an otherwise fixed whole.

But here’s the catch: Flux, at any point in the river, requires persistence. There can be no flux at points that merely happen. Nothing flows through an occurrence. Nothing flows in an instant.

To talk about movement through time — to talk about memory, or recurrence, or the rewinding of events — you need the events to still be there. You need the river to exist.

You need the manifold to endure.

And that means you’re not just working with a four-dimensional geometry of occurrences. You’re smuggling in a fifth-dimensional structure — a higher-order being that allows space-time to exist.

We don’t always say it out loud. But we always assume it.

That’s what makes devices like Hermione’s Time Turner work. She travels back to a moment before her last class began. From that point on, her worldline no longer flows forward in the usual way — it cuts back to an earlier moment; one she already experienced.

If she changes nothing in her previously lived timeline to the point when she cut back, she can attend a simultaneously occurring class and simply return to her timeline at the end and carry on. But if she interferes — say, by going back further and killing her grandfather before her father was conceived — she’d set off a new chain of events that’s inconsistent with her timeline up to the point when she used the Time Turner.

So what happens next?

Does eternity — space-time — update in a meta-instant? If so, does she remain within it, untethered — her timeline beginning from the moment she emerged in the past? Can she use the Time Turner again to go back and stop herself and fix her timeline?

Or does her entire timeline vanish along with the vanishing of her birth and early childhood? But in that case does her grandfather live and her birth occur?

Is the timeline somehow protected, as Hawking suggested?

Does an alternate timeline open up within a multiverse?

Could such things happen? Maybe.

But here’s what we know: These things cannot happen if eternity does not exist and cannot be travelled within. And there’s no physical evidence that the kind of five-dimensional persistence needed to support that story actually does exist.

As far as we know, the space-time manifold is not something that persists. It’s a structured description of what occurs.

And time travel, as we commonly imagine it, only makes sense if we quietly smuggle in the idea that space-time doesn’t just occur — but persists.

Time Travel in a Fixed Space-Time

Now, not all time travel stories are about rewriting the past. Some are about realising you can’t.

In The Terminator, the characters try desperately to change fate — but every choice they make leads them straight to the outcome they’re trying to avoid.

This is the other side of the time travel coin: The timeline that’s fixed. You can loop around in it, but you can’t change anything.

The future is already written. The illusion of choice persists, but the outcome never shifts.

But even the illusion of agency requires that something — consciousness, perspective, memory — flows through that fixed world. And that only makes sense if eternity itself endures.

This is the worldview of Slaughterhouse-Five. Billy Pilgrim becomes “unstuck in time,” revisiting moments throughout his life — but never altering them.

To the Tralfamadorians, every moment simply is — eternal, unchanging, equally real.

But think about what that means.

It means the whole manifold of events — the whole of space-time — must already exist. Fixed. Real. Complete.

Whereas we — people, living in reality — seem to experience a three-dimensional world that exists now, Vonnegut’s Tralfamadorians experience a fixed, four-dimensional eternity that exists meta-now.

Without that assumption — without that deeper existence — we’re left with something else entirely.

A four-dimensional elephant that flashes. A world-tube that occurs — that comes in and out of being, instantaneously, all at once.

No flow. No illusion. No memory. No time machines. No visiting Caesar. No saving the moment that sparked your parents’ love for one another. No flickers of awareness tracing a path through eternity.

Just everything happening, all at once, in a world that merely occurs.

Not one that exists.

Implications for Physics

So — what does time travel actually require? Not just physically, but conceptually.

It requires that we erase the difference between what happens and what is.

Time travel stories quietly treat events not just as things that occur, but as things that exist. As if they’re still there. As if they persist.

This is the move we’ve been tracking all along. It’s the collapse — the conflation of ontological categories that should be separate — that turns occurrences into enduring things. That reifies the event structure of space-time — treating it not as a record of what unfolds in existing reality, but as a higher-dimensional reality that exists.

And once that step is taken — everything else falls into place. Consciousness flows. Events recur. Timelines branch, and loop, and knot back together. Because the world — space-time, eternity — is supposedly still there. A reality to be moved through.

But that’s not a four-dimensional world. It’s a five-dimensional one. A hidden framework. An implicit ontology. One in which the entire manifold of events that happen — exists.

And that framework — whether acknowledged or not — is everywhere.

It shapes how physicists talk about relativity. It shapes how philosophers write about time. It underpins the metaphors. The thought experiments. The “block universe.” The idea that time is an illusion.

But if we take seriously what we’ve uncovered — if we hold the line between what exists and what merely occurs — then all of it falls away.

The time travel stories collapse. The eternalist metaphors dissolve. The paradoxes are gone. And so does much of the hidden scaffolding that’s been holding up our basic ideas in modern physics.

This isn’t just a problem for science fiction. It’s a problem at the heart of physics.

This piece is a revised and expanded version of this earlier post. While the core argument remains the same, the structure was been rebuilt for clarity, pacing, and depth. The above takes more time to lay the groundwork—but what emerges is sharper: a clear diagnosis of the conceptual move that underlies most time travel stories, and a demonstration of how that same move quietly shapes how physicists and philosophers often talk about space-time. What begins as a science fiction trope ends up revealing a deeper confusion — one that still lives at the heart of modern physics.

Leave a reply to From The Conversation: “What, exactly, is space-time?” – sciencesprings Cancel reply