Isaac Newton was born 25 December 1642—in the same year that Galileo died. A brilliant physicist and mathematician, Newton made significant contributions to the theories of optics, mechanics and gravitation, in addition to being credited (along with Gottfried Leibniz) with the invention of calculus.

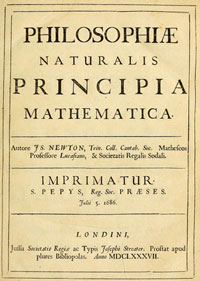

In a 1676 letter to Robert Hook, Newton penned one of the most famous quotes that has since been attributed to him: “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Indeed, the great fame of this quote may be partly due to its very appropriateness. For Newton was neither the first to imagine that there was some force emanating from the Sun through which the planets were held in orbit, nor was he the first to understand inertia. What Newton did was pull together the correct elements from scattered sources, rejected incorrect hypotheses (like Kepler’s view of the Solar System and Galileo’s theory of tides), and upon this basis he made further insights about the nature of the world. Newton’s great theories of mechanics and gravitation are described in his book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy; commonly called Principia), first published in 1687, and those theories became standard physics for more than two centuries.

Principia Mathematica. Source

The first part of Principia deals with Newton’s three laws of motion:

- The law of inertia: a body will continue at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless acted upon by an external force.

- The acceleration (a) of a massive body is directly proportional to, and in the same direction as, an applied force (F), and inversely proportional to its mass (m); symbolically,

a = F/m. - To every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Laws I and II describe how the motion of a body depends on the presence or absence of an external force, and were innovations on both Aristotelian and Galilean physics. Since Aristotelian physics was based on the principle of uniform circular motion, Newtonian physics was fundamentally different in this regard. But also, even though Galileo had realised Newton’s first law as a result of his experiments, he still grappled to justify a claim that the circular planetary orbits should be inertial as well, which is one reason why Newtonian physics was an innovation from Galilean physics. Law III, it turns out, was a key to unlocking Newton’s law of universal gravitation.

As noted already in this module, the most important difference between Kepler’s concept of a force from the Sun which held planets in orbit and Newton’s theory of gravitation is that Newtonian gravity acts everywhere. According to Newton, the force that holds the planets in their orbits is the same as the force that might cause an apple to fall onto the head of a person sitting under an apple tree. Furthermore, this force does not act in only one direction, say from Sun to planets and from planets to apples, but, according to Newton’s third law, the gravitational attraction must be mutual.

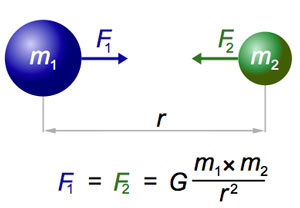

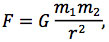

Newton’s law of universal gravitation states that between every two massive objects, m1 and m2, there is a force which is proportional to the product of the two masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them, r :

where G = 6.67 x 10-11 m3/s2/kg is a constant of proportionality, known as Newton’s gravitational constant. This one equation describes two equal and opposite forces: the gravitational force applied to m1 because of the presence of m2, and the gravitational force applied to m2 because of the presence of m1.

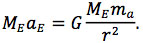

According to Newton’s second law, we know that this force must cause each mass to be accelerated. Let us examine the effects of the gravitational force between the Earth (ME = 5.97 x 1024 kg) and an apple (ma = 0.100 kg). Since the concept is less intuitive, let’s examine the force that the apple applies to the Earth. Using Newton II and Newton’s law of gravitation, we can find the acceleration of the Earth, aE, by equating the two forces:

Now we can look at just the equation given by the second equal sign:

Since ME shows up on both sides of the equation, we divide both sides by ME to obtain

Notice that this result is independent of the Earth’s mass: if we had instead worked out the acceleration of the apple, aa, we would have found a similar expression involving ME in place of ma. This describes precisely Galileo’s observation that the acceleration of a falling mass is independent of the value of its mass; thus, e.g., a golf ball and a bowling ball fall towards the Earth at the same rate.

Now, there is one other value in the expression for aE that has not yet been properly defined: r, the distance between the Earth and the apple. This is not the distance between the apple and the surface of the Earth. Rather, it is the distance between the centre of the Earth and the centre of the apple. Therefore, for an apple that is initially only a few metres from the surface, we can approximate r = RE = 6.371 x 106 m, where RE is the radius of the Earth. Inserting this value along with the above values for G and ma, we find aE = 10-18 m/s2—i.e. the apple’s gravitational attraction really doesn’t do much to accelerate the Earth, as we should expect.

Learning Activity

while the apple’s gravitational attraction doesn’t do much to accelerate the Earth towards it, we know that the apple is accelerated towards the Earth at an appreciable rate. Derive a similar expression for aa as we gave for aE above, and show that its value is 9.80 m/s2.

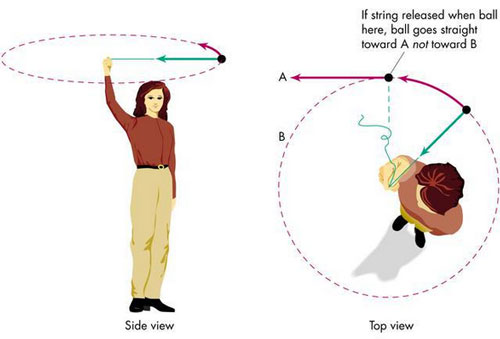

The example of the apple and the Earth shows that massive bodies—whether large or small—all exert a force that accelerates all other bodies towards them. But how does this explain planetary orbits? The key to understanding this is to think of the velocity of the planets, which are always in motion. Newton’s first law says that an object will remain at rest or will move uniformly in a straight line unless acted upon by an external force. An elliptical orbit is not a straight line; therefore, there must be a force that keeps the planets from moving in a straight line. This is the mutual gravitational force that acts between planet and Sun. You can understand this by thinking of a ball on the end of a string that you spin horizontally above your head: by maintaining tension in the string, pulling the ball in towards your hand, you keep the ball from flying off in a straight line—which is what would happen if you let go.

It turned out that Newton could account for each of Kepler’s laws through his universal law of gravitation. Indeed, Newton’s proof of Kepler’s first law is one of the most famous stories in the history of science. In 1684, Edmund Halley (the astronomer best known for computing the orbit of Halley’s comet) visited Newton to ask what path he thought a planet would follow in the presence of an inverse square force (i.e. in the presence of a force that diminishes with the inverse square of the distance, as ![]() ). Newton immediately replied that it would be an ellipse, as he’d done the calculation himself; but he was unable to find the calculation among his notes. However, this interaction with Halley prompted a flurry of work which resulted, after just eighteen months, in the composition of the Principia—where Newton did indeed demonstrate that the

). Newton immediately replied that it would be an ellipse, as he’d done the calculation himself; but he was unable to find the calculation among his notes. However, this interaction with Halley prompted a flurry of work which resulted, after just eighteen months, in the composition of the Principia—where Newton did indeed demonstrate that the ![]() relation would result in elliptical orbits.

relation would result in elliptical orbits.

Newton similarly explained the other two of Kepler’s laws in precise mathematical terms through his universal law of gravitation. Qualitatively it is easy for us to see how this works, so let us begin with Kepler’s second law. As a planet moves closer to the Sun, it should be accelerated so that it moves more quickly along its orbital path until it reaches the closest point to the Sun in its elliptical orbit. As it then moves away, it should slow down. Since Newton’s law of gravitation gives a precise mathematical expression, it can be used to prove that this occurs in such a precise way that a line drawn from the Sun to a planet sweeps out equal areas in equal time intervals.

Similarly, given that Newton’s law is an inverse square law, we know that the acceleration due to gravity will be greater near the Sun; therefore, a planet will need to move more quickly when closer to the Sun in order to maintain its orbit (and not fall in due to the stronger gravitational force). Thus, as a planet’s orbital distance decreases, the orbital period should decrease as well. As Newton showed, when the period p is measured in years and the semi-major axis of the orbit—i.e. the planet’s average orbital distance—is measured in Astronomical Units, according to Newton’s law of universal gravitation the precise relation between the two must be Kepler’s third law:

p2 = r3.