In order for a physical theory to be successful, one criterion is that it should explain, and therefore be confirmed by, as many independent observations as possible. And in this regard, one of the greatest successes of Newton’s theory was its ability to finally—in 1687—explain the ebb (tide out) and flow (tide in) of the tides.

In order to appreciate how great an achievement this was, it is useful to consider earlier proposals, so we begin with Galileo’s theory of tides which was completely› wrong. The theory can be understood by imagining water sloshing around in a container. Galileo’s theory was, effectively, that the combination of the Earth’s motion around the Sun and its daily rota›tion causes the seas to slosh around in a way that produces the tides. In this way, since one side of the Earth is always spinning in the same ›direction as the Earth orbits, while the other half moves against the Earth’s orbital motion, Galileo reasoned that the tides should follow a 12-hour cycle.

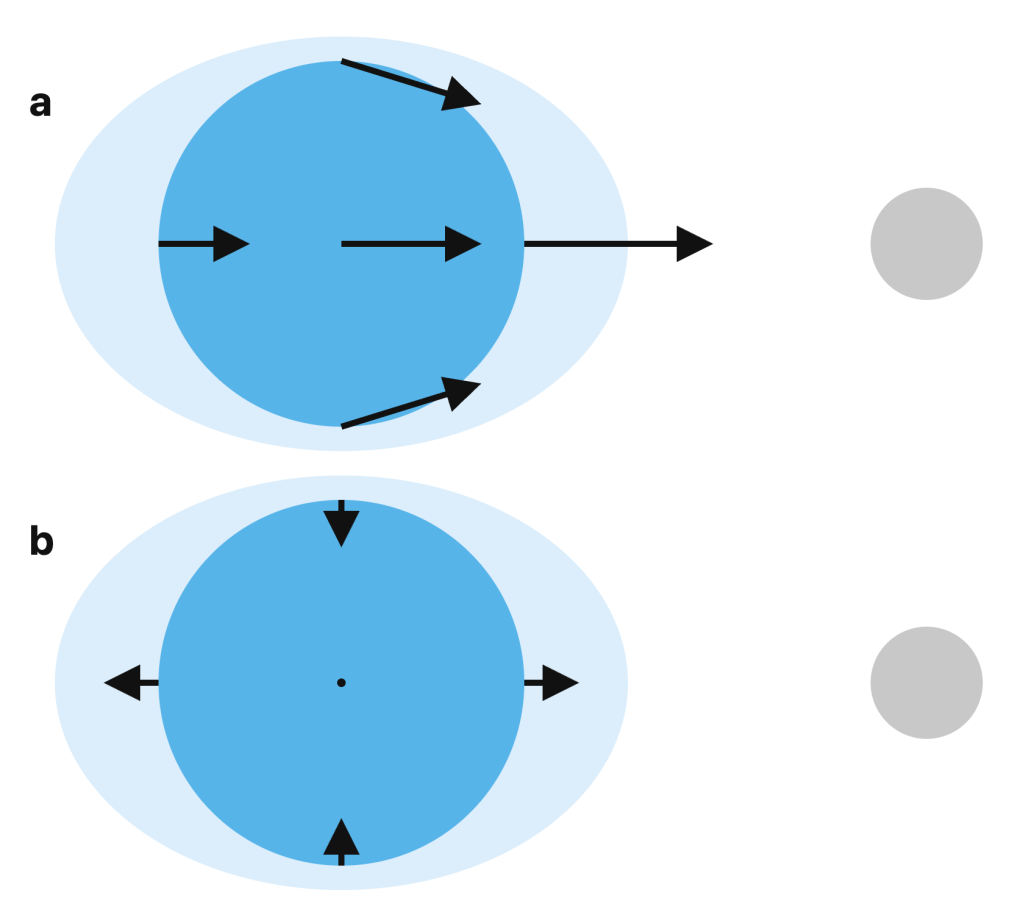

Newton’s explanation—involving a differential gravitational attraction between the Earth and Moon—is completely different. Consider Figure 3-22a. Due to the inverse-square form of the gravitational force, the side of the Earth nearest to the Moon is pulled more strongly than the middle of the Earth, and the middle of the Earth is pulled more strongly towards the Moon than the far side of the Earth. Figure 3-22b shows the difference between the forces on the outside of the Earth compared to the pull on the middle of the Earth. From this perspective, we see that the liquid water on the side nearest to the Moon bulges out towards the Moon while the liquid water on the opposite side of the Earth is somewhat left behind, and therefore also bulges. As this water bulges, the tide goes out (ebbs), and when the Earth has rotated another 90-degrees the tide comes in (flows).

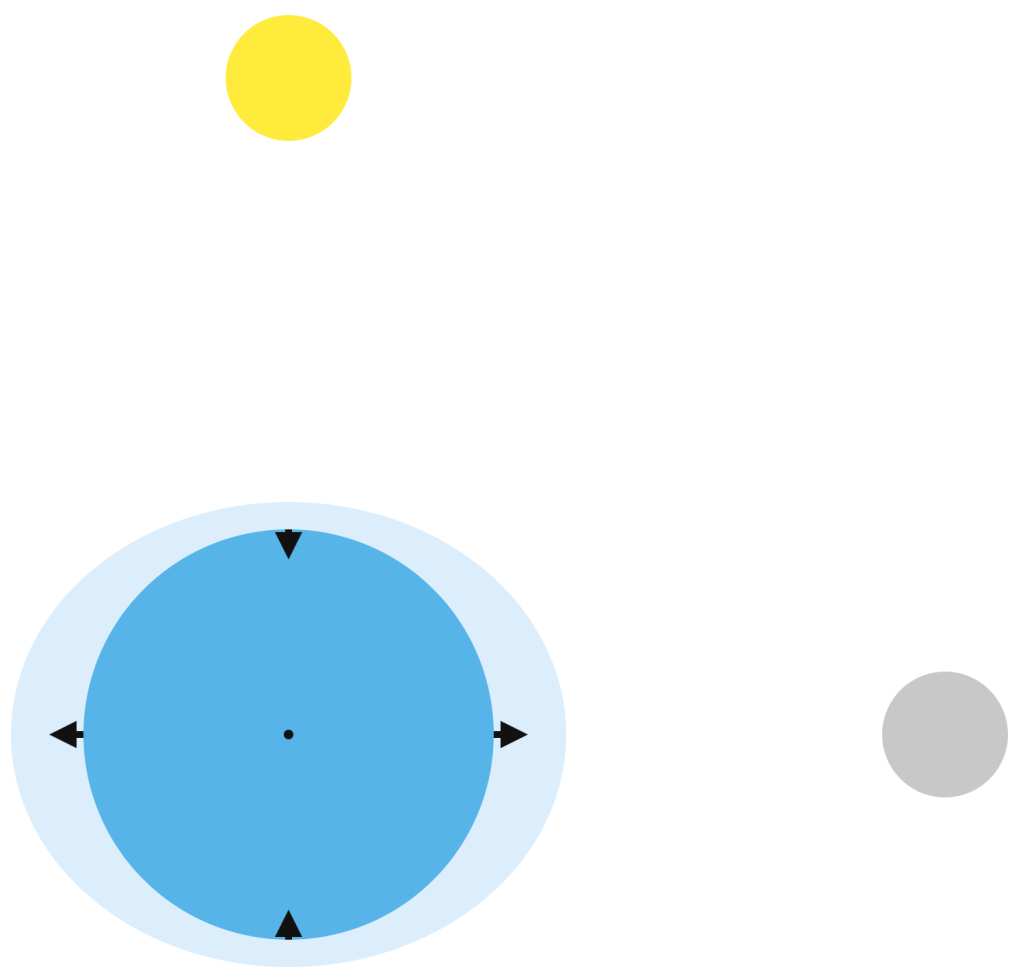

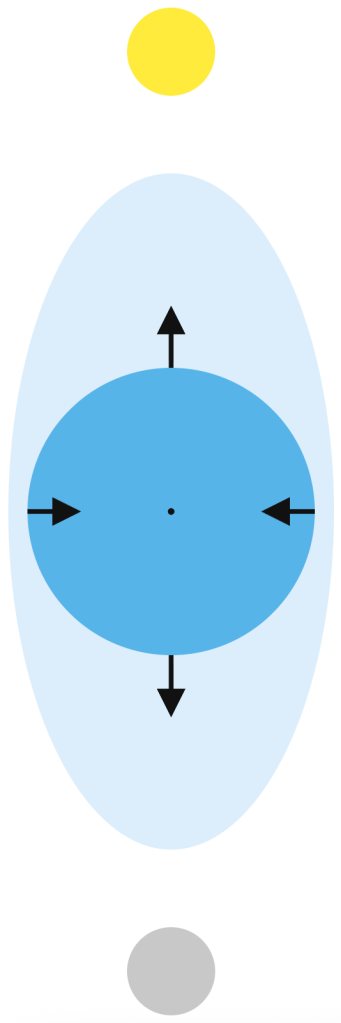

But Newton’s explanation does not stop there. Throughout the course of a month, the Moon’s tides range from strong spring tides which occur at new and full Moons (Figure 3-23), and relatively weak neap tides which occur when the Moon is at first and third quarter (Figure 3-24). This phenomenon is explained with the addition of the Sun’s tidal force on Earth. Despite being weaker than the tidal force from the Moon (roughly half), the Sun’s tidal force does add a non-trivial effect. When the Sun, Earth and Moon are aligned at the new and full Moons, the tidal force from the Sun adds to the Moon’s tidal force producing the most dramatic tides. When the Earth-Moon and Earth-Sun lines are perpendicular, the two tidal forces counter each other and the tides are the least dramatic.

(Note that this effect is displayed schematically in Figures 3-23 and 3-24, where the vector magnitudes and the halo elongation have been increased or decreased, respectively, by a factor of 1/2 relative to the scaling shown in Figure 3-22b.)

Newton’s Principia was perhaps the greatest single achievement in the history of physics. It explained Kepler’s laws, the tides, and it incorporated (the good parts of) all of Galilean physics. In fact, Newton’s law of universal gravitation suffered from only one nagging issue: action at a distance. Newton’s critics were quick to point out that the hypothesis of a gravitational force acting instantaneously from a distance lacked rational explanation. Newton responded that it was enough that the gravitational attraction between bodies was implied by the phenomena, as the mathematical theory demonstrated, even without indicating its cause. And in regard to this cause, Newton famously refused to speculate, stating instead, “hypotheses non fingo” (I frame no hypotheses). He didn’t know why the law worked: all he knew was that it did. The matter would have to wait more than 200 years before it would be resolved by Einstein.