Kepler was born on 27 December, 1571, a century after Copernicus and nearly eight years after Galileo. While Kepler was actually younger, his story takes place before Galileo’s, and so we discuss his contributions first.

Kepler was born in a town called Weil der Stadt, on the edge of the Black Forest in Germany. He attended the nearby University of Tübingen, where he studied astronomy under Michael Maestlin (Figure 3-6)—one of the first astronomers to teach both the Ptolemaic and Copernican systems in the classroom. It was then that Kepler developed his belief that the planets not only orbit the Sun, but that the Sun is the source of that motion, which he defended on both theoretical and theological grounds. Throughout his life, Kepler maintained that the Sun exerted a physical force on the planets which caused their orbits. This idea was both speculative and evolving in nature, e.g. as he thought at one time that it might be a magnetic force from the Sun that bound the planets to their orbits.

This point concerning Kepler’s ideas about the Sun’s influence on planetary orbits provides a good example of his character. In contrast to Copernicus, Kepler had a great imagination: he was a creative thinker, always coming up with new ideas that he thought would explain celestial motions. He believed there was a physical explanation for those motions, that nature should be full of beautiful symmetries, and that God must have created the world with those in mind. Kepler was also a brilliant mathematician, capable of working out the mathematical consequences of his wild speculations. Because of this combination of mathematical brilliance and unbridled creativity, Kepler was both willing and able to try things that no one had ever tried before. Finally—and most importantly—Kepler was a stickler for precision: if the model did not fit the observations, he accepted that it must be wrong and moved on and investigated a new one.

Kepler’s biography is very entertaining. Along with an interesting personality, which he preserved for us in major works that were written more like a diary of his evolving ideas about reality than as conventional research publications, his life was filled with drama due to constant financial trouble and the strain that placed on family life. The need to find work, combined with the tensions of life during the Protestant Reformation in Europe—even the need to defend his mother at her witch trial—meant that Kepler had to live in many places throughout his life. The most productive years of Kepler’s life were those he spent in Prague as Imperial Mathematician to the Holy Roman Empire (1601-1612), a position which was secured for him by his predecessor and most important benefactor, Tycho Brahe (1546-1601; see Figure 3-7).

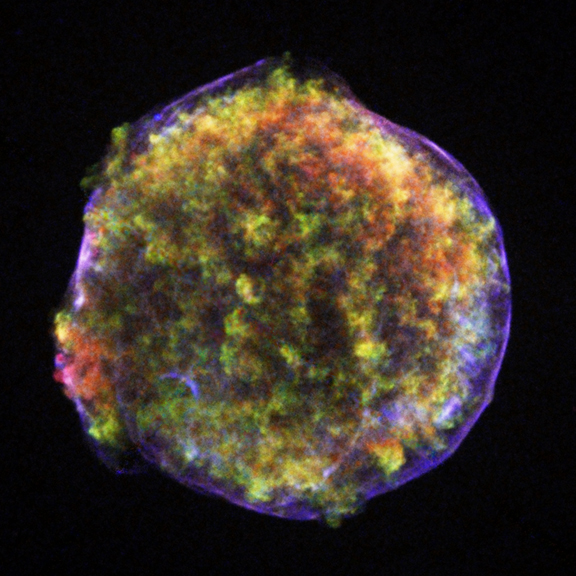

Tycho is best remembered as a brilliant astronomer who compiled an astronomical record of unprecedented accuracy using a number of instruments of his own design, since, as we’ll see, that record was crucial to Kepler’s discoveries. In Tycho’s book, De stella nova (On the new star), he presented evidence against the Aristotelian belief that the cosmos beyond the Moon is constant and unchanging, as he had shown that the “new star” of 1572, now known as Tycho’s supernova (see Figure 3-8)), did not exhibit any parallax shift. Tycho also famously rejected the crystalline spheres of Aristotle, which both Ptolemy and Copernicus had incorporated into their models. The reason was again due to parallax measurement: Tycho noted that the comets exhibited a smaller parallax shift than the Moon, and were therefore not atmospheric phenomena (as had previously been assumed, since they come and go), but celestial objects that exist beyond the Moon; therefore, he argued that the planetary crystalline spheres could not exist, as the comets’ paths would intersect them.

In addition to making these important discoveries, however, Tycho was also misled by his own accurate observations. For example, he found that stars appeared as disks in the sky with varying widths, and the angular diameters he measured could be as much as a few arcminutes; however, nearly every star in the sky is actually unresolvable even with modern telescopes. The apparent widths that Tycho observed were really an atmospheric effect. But because he thought he could resolve the angular diameters of the stars, and because they exhibited no measurable parallax shift, Tycho was led to a false conclusion. He argued that if the Earth were orbiting the Sun (as Copernicus had famously proposed), the lack of parallax shift implies that the stars must be so far away that, given their apparent angular diameters, they’d have to be larger than the orbital radius of the Earth.

Tycho was an excellent scientist, and this incident serves to illustrate an important part of the scientific method: with every observation we make, we infer something about reality that we believe to be the “true” cause of the phenomenon—the thing we’ve observed—and any false inference we make can easily lead to another. Because Tycho didn’t realise that the apparent diameters of stars are really caused by something astronomers call atmospheric seeing, he falsely concluded that either the stars must be extremely large or the Earth really isn’t moving. On this basis, Tycho famously proposed his geo-heliocentric solar system model, in which the Sun and Moon orbit a stationary Earth while the planets all orbit the Sun (see Figure 3-9).

The Sun, Moon and stars orbit the Earth, while the five planets orbit the Sun. Source

Following a series of disagreements with the new Danish king Christian IV, Tycho moved to Prague in 1597 as Imperial Mathematician—an event which proved to be one of the most important in leading (indirectly) to the Scientific Revolution. For it so happened that in his youth, smallpox had left Kepler with poor vision and crippled hands, so that he could never have begun testing his theories against observational evidence without the help of an astronomer. And with Tycho’s move to Prague, the best observational record of the day (Tycho’s) had come within Kepler’s reach, at the time of his career when he needed it most.

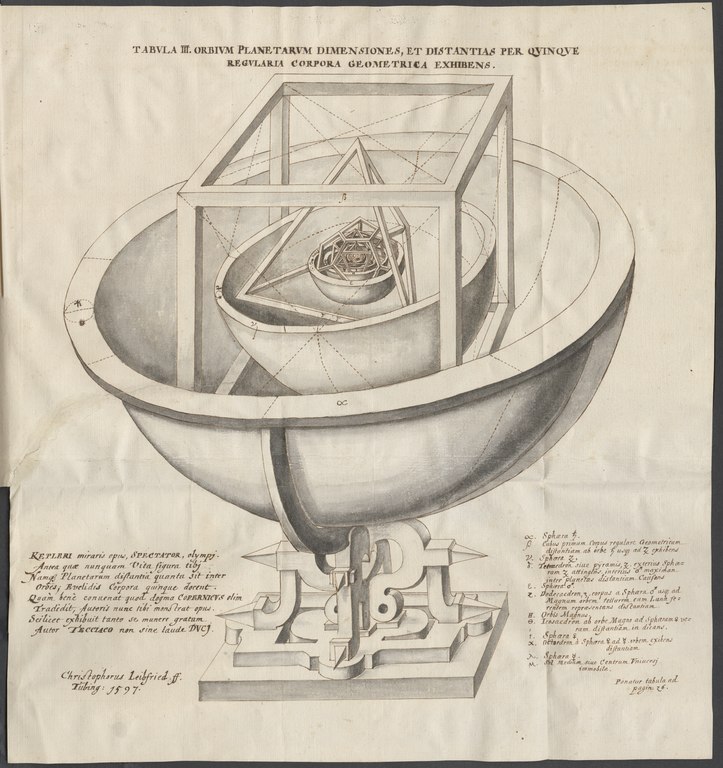

Two years before Tycho’s move, in 1595, Kepler came upon an idea that would guide his research for the rest of his life: from that time on Kepler believed that the Aristotelian spheres in which all six planets (that is, Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn) should orbit the Sun, were nested between a series of five Platonic solids—the octahedron, icosahedron, dodecahedron, tetrahedron and cube. The Platonic solids (named after Plato) that Kepler thought of as the key to unlocking the cosmic mystery, are the only three-dimensional shapes with the properties that

- they are composed of congruent regular polygonal faces—i.e. each face is a polygon with the same shape and size as every other face, and the interior angles of these must all be equal (e.g., as with squares and equilateral triangles)—and

- the same number of polygons meet at each vertex (e.g. three squares meet at each vertex of the cube, and four equilateral triangles meet at each vertex of the octahedron).

five Platonic solids are embedded between six planetary

spheres. Source.

The Platonic solids are a very special type of geometrical object, and Kepler believed that God would have wanted to incorporate their beautiful symmetries into the solar system when he designed it. In fact, he thought this explained why there had to be six planets. Kepler’s scheme, which he described in his Mysterium Cosmographicum (1596), was that each planetary sphere should be surrounded by a Platonic solid, with the sphere touching the centre of each polygon; and each Platonic solid should be surrounded by a planetary sphere, with all vertices of the Platonic solid touching the outer planetary sphere. For example, think of a sphere inside a cube, which is large enough to just touch the centre of each square, and surround that with a sphere that is just small enough that every corner of the cube touches the inside of the sphere. This sequence would enable all five Platonic solids to be nested within the six planetary spheres. More than a decade after Kepler discovered that planets follow elliptical orbits, he was still trying to find the right dimensions for this model.

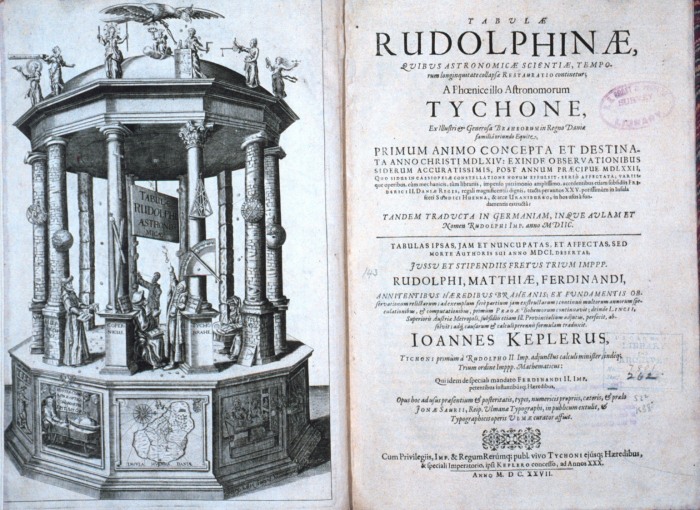

Having come up with his grand idea of the universe, Kepler was both anxious to share it with others and in need of a means to verify it. He sent many copies of the Mysterium Cosmographicum around Europe when it was printed in 1597, and one of the people he sent it to was Tycho Brahe. Although Tycho would never adopt Kepler’s theory, they corresponded over the next few years and, when religious tensions began to threaten Kepler and his family around 1600, Tycho invited him to Prague to be his assistant. As Imperial Mathematician, Tycho’s main task was to produce an updated set of astronomical tables, to be called The Rudolphine Tables after the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II, which he intended to base upon his own geo-heliocentric system. Tycho died unexpectedly less than two years later and Kepler succeeded him as Imperial Mathematician, inheriting all of Tycho’s observational data as well as the task of producing The Rudolphine Tables.

Once Kepler was in possession of Tycho’s data and had settled into the regular tasks required of his position (such as Imperial Astrologer), he began searching for a pattern of regular motion that would accurately fit to Tycho’s careful observations of Mars’ motion. To begin with, he made three innovations on the Copernican system:

- Since he regarded the Sun as the source of planetary motion, he decided to make it the focal point of all planetary motion—i.e. rather than having the Earth orbit a point on an epicycle going around a deferent that was centred on the Sun, he put the Sun at the focus.

- Whereas Copernicus had described the motions of all the planets from the perspective of a single orbital plane, and then used epicycles to make them move up and down out of the plane, Kepler first postulated that all planets orbit within a single plane and that their orbital planes are at angles with respect to each other (which they actually are); then, he verified that Mars’ orbital plane is tilted 1°50’ relative to Earth’s.

- Once more on the basis of his conviction that the Sun is the source of planetary motion, Kepler rejected Copernicus’ very basis for proposing a heliocentric system—uniform circular motion;—he reintroduced the equant and rejected the use of epicycles, arguing that planets should move more quickly when they are closer to the Sun—the source of their motion (so the equant would be justified as something more realistic than the principle of uniform circular motion)—while there is no physical basis for epicycles (at least none that anyone ever thought of).

On the basis of these three points, Kepler began calculating Mars’ orbit. After seventy repetitions in the course of five years, he arrived at a description which agreed with the data to within two arcminutes, which was the uncertainty in Tycho’s measurements. In modern language, the process of adjusting the parameters of a model that Kepler had completed in order to make the model fit the data as closely as possible is known as calibration. Kepler had at last found a well-calibrated model that fully agreed with the data he used to calibrate it; therefore, given the date and time of any one of his data points, Kepler could calculate a theoretical value for the position of Mars at that time, and the calculated position would fall within the uncertainty bounds of the measurement. He then wrote out three pages of tables showing that his results agreed with all the data to within the acceptable measurement uncertainty.

But in order for a model to be of any use, it must do more than agree with the data it has been tweaked to fit in the calibration phase: it must be predictive—i.e. it must accurately predict the locations of other data points that were not used in the calibration process. In order to test the accuracy of his model’s predictions, Kepler had set aside two observations. And with his model ready he finally compared those values to his predictions, only to find that his calculations were out by eight arcminutes—four times the measurement uncertainty.

Kepler had to abandon a model that had taken him five years to develop, because his calculations disagreed with two observations. He did so, apparently without a second thought. There is an excellent quote from the great twentieth-century physicist, Richard Feynman, who said “It doesn’t matter how beautiful your theory is, it doesn’t matter how smart you are. If it doesn’t agree with experiment, it’s wrong.” It’s best to hear Feynman say this in his own words so that the meaning really sinks in:

Kepler is commonly regarded as one of the greatest scientists of all time, and it is precisely because of his ability to throw away a wrong theory and start fresh when the data required it. If he hadn’t, he never would have discovered his laws of planetary motion.

The book containing this entire analysis is called Astronomia Nova—the New Astronomy. It was not published until 1609 due to disputes with Tycho’s heirs over Kepler’s use of the data. Astronomia Nova also contains the original statement of Kepler’s first two laws, which he discovered after rejecting his first attempt at describing Mars’ orbit. He closed the analysis of this first attempt with the following statement:

And thus the edifice which we erected on the foundation of Tycho’s observations, we have now again destroyed… This was our punishment for having followed some plausible, but in reality false, axioms of the great men of the past (Koestler, 1959).

Kepler had already rejected uniform motion, and in the next phase of his analysis he would eventually reject circular motion as well—a plausible, but in reality false, axiom of the great men of the past. He began by analysing the orbital speeds of Earth and Mars, and discovered what is now known as Kepler’s Second Law (although he discovered it first): a line drawn from the Sun to each planet sweeps out equal areas in equal time intervals.

Kepler attempted one last time to describe Mars’ motion with a circular orbit and failed. He concluded that this is because its path is not a circle, but an oval. He didn’t like it—he didn’t think it was beautiful—but as it turns out, he was right—and that is all that matters. The type of oval that Kepler was looking for was an ellipse, but he did not immediately realise it. He spent a full year investigating the hypothesis that, after all, there must be some physical justification for epicycles, and that the correct deferent-and-epicycle orbit should ultimately result in an egg-shaped path around the Sun. He reflected later: “What happened to me confirms the old proverb: a bitch in a hurry produces blind pups” (Koestler, 1959)—i.e. as he came to realise once more that the hypothesis would not be confirmed, he decided that he had been too hasty in laying the egg. Finally, following one last series of missteps, he came to his First Law: the planets follow elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus.

Perhaps more than anyone else in the history of physics, Kepler’s work illustrates how blind we are to the underlying truth of physical reality—how every theory we ever construct is the description of a shadow based on assumptions we have to make about the things that cause the shadows to appear—and how, since we can never determine the causes of those shadows with absolute certainty, the best we can do is to ensure that our assumptions lead to the most accurate descriptions possible. At every stage of Kepler’s research, he was firmly convinced that he finally had the right basic idea, and that he only needed to determine the mathematical particulars that would provide an accurate fit to the data. For a whole year, he was completely convinced that the planets followed egg shaped orbits around the Sun, and that a sort of reaction of the planets to the Sun’s gravity should be physically responsible for the necessary epicycles that conspired to produce an egg-shaped orbit. It was a last-ditch effort to make circular motion work. When he was finally convinced that the attempt had failed—that his egg would never fit the observations—he gave it up as a lost cause, convinced that it could never have been otherwise.

Even after Kepler had discovered that planets follow elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus, and that a line drawn from the Sun to each planet sweeps out equal areas in equal time-intervals (see Figure 3-12)—i.e. after he had discovered his First and Second Laws—he was nowhere nearer to understanding how planetary motion really works. He knew these principles resulted in an excellent fit between theoretical model and observational data, but he was no closer to understanding why. He discovered his Third Law in the process of writing Harmonice Mundi (The Harmony of the World), which was completed in 1618 and was to be his great masterpiece, completing what he had started in Mysterium Cosmographicum. Kepler was convinced that God had created the world according to geometrical symmetries relating to the harmonic ratios, and that the nesting of Platonic solids within spheres that held the planets’ elliptical orbits should provide the basic physical backdrop for the theory. After a number of brute force, trial-and-error attempts to find a particular ratio between the radius of a planet’s orbit and its orbital period, Kepler finally discovered his Third Law: the square of a planet’s orbital period is equal to the cube of its average distance from the Sun.

If we denote the planet’s average distance from the Sun, the semi-major axis of its elliptical orbit, by the letter r, and denote its orbital period by the letter p, Kepler’s Third Law states that

p2 = r3,

where p must be measured in years and r must be measured in Astronomical Units (A.U.). Quite apart from the fact that Kepler incorrectly assumed this ratio was related to a musical harmony that God decided to encode in His decoration of the world, it is important to note that Kepler could only make the discovery because he believed that the Sun had an influence on planetary motion. It was upon that basis that he reasoned that a planet’s orbital speed, and therefore its orbital period, should be related to its distance from the Sun. In contrast to Ptolemy and Copernicus who had approached the problem of describing planetary motion from a purely mathematical standpoint, not concerning themselves with any need to physically justify the use of deferents, epicycles, etc., Kepler did feel that there must be a physical basis for the motion of the planets—and it was by considering how the Sun might influence planetary orbits that Kepler discovered his Third Law. It was because Kepler began with the right question—What is the physical cause of planetary orbits?—that he made one of the most important advances in the history of physics, which eventually contributed to the discovery of Newton’s theory of gravitation.

Learning Activity

Kepler’s predictions of planetary motion were made with unprecedented accuracy, and therefore amounted to strong evidence for both Kepler’s Laws and for the heliocentric hypothesis revived by Copernicus. However, would Copernicus really have been pleased with Kepler’s results? Which aspect of Kepler’s system do you think Copernicus would have liked the most, and which do you think he would have liked the least? No doubt Copernicus and Kepler had very different ideas of what would amount to a beautiful theory of planetary motion, and both were guided by their individual ideas. On the other hand, in the end it would turn out that neither Copernicus’s principle of uniform circular motion, nor Kepler’s idea of the essential place of Platonic solids, has anything to do with reality as we know it today. Even so, how likely do you think it is that either of them would have achieved what they did without the preconceived notions they were trying to validate?

Regardless of the personal aims of their discoverer, Kepler’s Laws—the three mathematical principles confirmed through the accuracy of The Rudolphine Tables—were essential to the discovery of Newton’s law of universal gravitation. However, the very name of the law indicates that it must apply to more than just planetary orbits—that it applies everywhere, including here on Earth. Kepler’s Laws could at best be seen as a model of celestial physics (as Kepler had intended), if not simply a model of mathematical astronomy (as many would have had it; see discussion of Galileo Affair later in the Learning Material). In order for the universality of Newton’s law to be realised, other important discoveries relating to the motion of heavy objects in a terrestrial setting were required. Foremost among those who contributed to the early science of motion was Galileo.