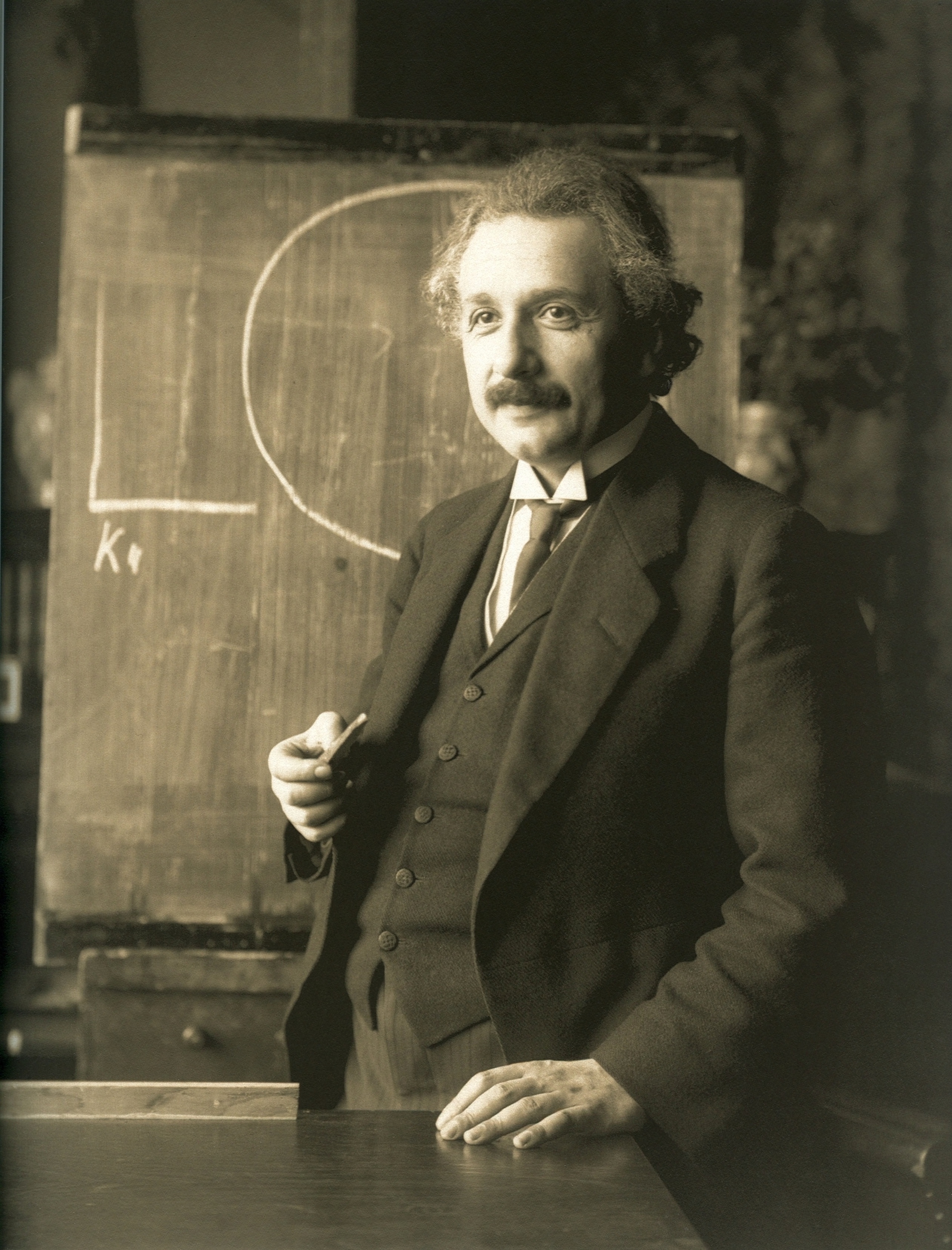

In 1905, at the age of 26, Albert Einstein became famous when he published his special theory of relativity. The consequences of this revolutionary idea theory range from time passing more slowly and lengths contracting when measured by observers in relative motion, to a recognition that “motion” can’t be objectively defined, to the famous relationship between mass and energy, namely

E = mc2.

The special theory of relativity is based on two simple principles:

- Observers can never detect their own uniform motion except relative to other objects, and the laws of physics can therefore always be used to describe the world as if any such observer is at rest (the principle of relativity); and

- The speed of light in a vacuum is a constant, c, which has the same value regardless of one’s state of relative motion (the light-postulate).

Having established his special theory of relativity, which was valid only in the case of uniform relative motion, Einstein sought a general theory that could be used to describe physics independent of whether one would be accelerated or in an inertial state. The eventual result was his general theory of relativity, published in 1915.

The main guiding principle behind Einstein’s development of general relativity, known as the equivalence principle, came from a thought experiment much like the one of Oresme and Galileo (which implied the relativity of inertia). In essence, the equivalence principle simply takes the notion of relative inertia a step further. In this case, consider a person jumping out of a plane holding a ball. If the person lets go of the ball, both would continue accelerating towards the Earth at the same rate. If we put a giant box around the person and the ball, neither would fall to the floor of the box, since all three objects (box, person and ball) would fall with the same rate of acceleration. For this reason, the person would experience a sense of weightlessness, as if they were instead far out in outer space. If, rather than simply letting go, the person threw the ball, they could describe its relative motion as if everything were happening in deep space, far from any gravitational force. In this case—the case of free fall in a gravitational field—the correct physical theory for describing the relative motion of inertial objects like the person and the ball is the special theory of relativity. Years later, while reflecting on the development of the general theory of relativity, Einstein described this as “the happiest thought of my life”.

Without getting into the complex mathematical details of the general theory of relativity, we can most easily understand the reason why this thought was so profound for Einstein by considering a direct consequence. If free fall within a gravitational field is equivalent to being in a perfectly inertial state, then it must also be true that being at rest somewhere in a gravitational field is equivalent to being accelerated relative to some perfectly inertial state. The equivalence principle states that

observers cannot distinguish between applied inertial forces (the kind described by Newton’s second law) and uniform gravitational forces in their nearby surroundings.

This means that if you were to board a rocket ship out in deep space, then while it remained motionless you’d feel the same sense of weightlessness as you would if it were falling towards the Earth. And if it were to accelerate at 9.8 m/s2 when you hit the thrusters, you’d be pushed down into your chair with the same force as if the rocket ship were sitting on the surface of the Earth.

Learning Activity

Imagine yourself in an elevator that is accelerating upward at a uniform rate. The equivalence principle states that you would feel the same force pushing you towards the floor of the elevator as if you were on a giant planet with the equivalent acceleration due to gravity. Using the Newtonian physics formulae, calculate the acceleration due to Gravity on the surface of Jupiter (MJ = 1.9 x 1027 kg; RJ = 7 x 107 m). The ratio of any acceleration to the gravitational acceleration near Earth’s surface, g = 9.8 m/s2, is commonly called the g-force. What g-force exists on the surface of Jupiter? Compare this to typical examples of g-force, such as those listed in this table. Assuming Jupiter had a solid surface, in what situation on Earth might you find yourself experiencing a force similar to the one you’d feel standing on that surface?

General relativity is not a simple theory to wrap your mind around, but for our purposes all you need at this point is to be comfortable with the concept that if you were inside a box you couldn’t tell whether the box was being uniformly accelerated or sitting at rest in a gravitational field. If you can accept that, then you’re prepared for the next step, in which general relativity gets a whole lot weirder.

Consider yourself inside a box that has a small hole for light to get through. If a light source shines horizontally into the box and the box is not moving relative to the source, the path of light through the box must be a horizontal line (see Figure 3-26). However, if your box is moving vertically upward at a constant rate while the light beam travels through it, the light beam must eventually intersect the box at a lower point on the far side from where it entered. Since your box is moving upward at a constant rate, and the beam of light is moving horizontally at a constant rate, it will appear to you to travel downwards across the box along a straight line. Finally, if your upward-moving box is accelerated, the path of the light beam will be curved downward from your perspective, since you’ll be moving faster with each passing moment, so it will cover an ever greater vertical distance as time passes.

velocity, or accelerated in the direction perpendicular to a beam of light. Source

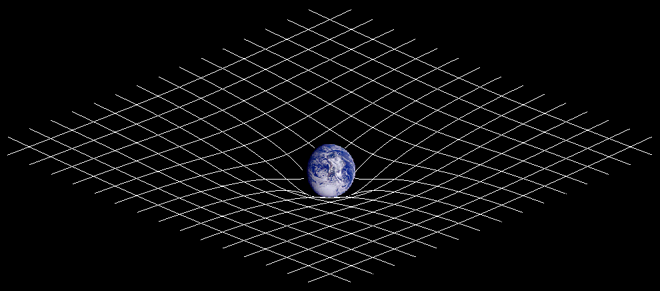

You may start to see where the equivalence principle comes in. If gravity and acceleration are effectively the same thing, then this simple “thought-experiment” tells us that light—with no mass—must bend towards gravitational sources. Now, the key to general relativity isn’t just this realisation—that light rays should be bent by gravitational fields—but really the way that Einstein explained how the bending of light rays occurs. Rather than thinking of space in the way that one normally thinks of space, and rather than thinking of the bending of light rays as result of a gravitational force that causes them to accelerate downwards, Einstein proposed something fundamentally different. In fact, general relativity—our current theory of gravity—doesn’t even describe gravity as a force.

According to Einstein, the path that light takes through space is described as “straight”, in much the same way as the person falling out of the plane is described as being “at rest.” However, space itself is supposed to be curved. According to general relativity, space is to be thought of as a gravitational field, and the curvature of that field is the source of the acceleration of both massive and massless objects. According to general relativity, the presence of mass curves space, and in turn the curvature of space tells matter how to move (see Figure 3-27).

That, in a nutshell, is Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Instead of describing light as being accelerated by gravity, he described space as a curved gravitational field through which things like light and people falling from planes take the most direct route. When the gravitational field is weak, that route is a straight line; when the field is warped, that route curves as well. And instead of describing gravitation as a force that acts at a distance between two massive objects—something Newton’s critics never could stomach about his theory—Einstein described gravitation through the concept of a field which is locally influenced by the matter in it, and which in turn dictates the natural path that any object through its local curvature.

Einstein’s idea of describing gravitation through inertial objects that take the most direct routes through warped space might have been viewed simply as the delusions of a warped mind—except that his theory has turned out to provide the most accurate description of observables. Recall Feynman’s statement about how the experimental confirmation of guesses is the foundation of science. In this case, Einstein’s theory beats Newton’s hands-down.

We’ll end our discussion of Einstein’s general theory of relativity by describing three important experimental confirmations. Two of these occurred in the first few years after the publication of general relativity, while one is a more recent test which you’ve likely taken advantage of on a regular basis.

The first test is tied in with the story of the planet Vulcan, which you may or may not have heard of. In 1859, the French mathematician Urbain Le Verrier hypothesised that if this planet existed between the Sun and Mercury, its gravitational effect on Mercury’s orbit could explain a discrepancy between observation and the description of Mercury’s orbital path given by Newtonian physics. Vulcan never was discovered, and Le Verrier’s hypothesis may seem like wild speculation—except that his own similar calculations a decade earlier had led to the discovery of Neptune through to its effect on the orbit of Uranus. In that instance, Le Verrier had been able to predict Neptune’s position within 1° of its actual location.

which is explained by general relativity. Source.

So, what’s the deal with Mercury’s orbit? As Mercury orbits the Sun, its elliptical orbit gradually rotates around the Sun so that the location of its perihelion precesses by 574 arcseconds per century (see Figure 3-28). This is mainly due to the gravitational effects of other Solar System planets, although the prediction from Newtonian physics which takes all these effects into account is that Mercury should precess by only 531 arcseconds per century. Le Verrier’s hypothesis was that Vulcan’s gravity would account for the other 43 arcseconds, but as we now know the prediction was not correct. In 1916, Einstein explained the discrepancy as a general relativistic effect, showing that his theory predicts that Mercury’s orbit should precess relative to the Newtonian prediction by exactly the right amount.

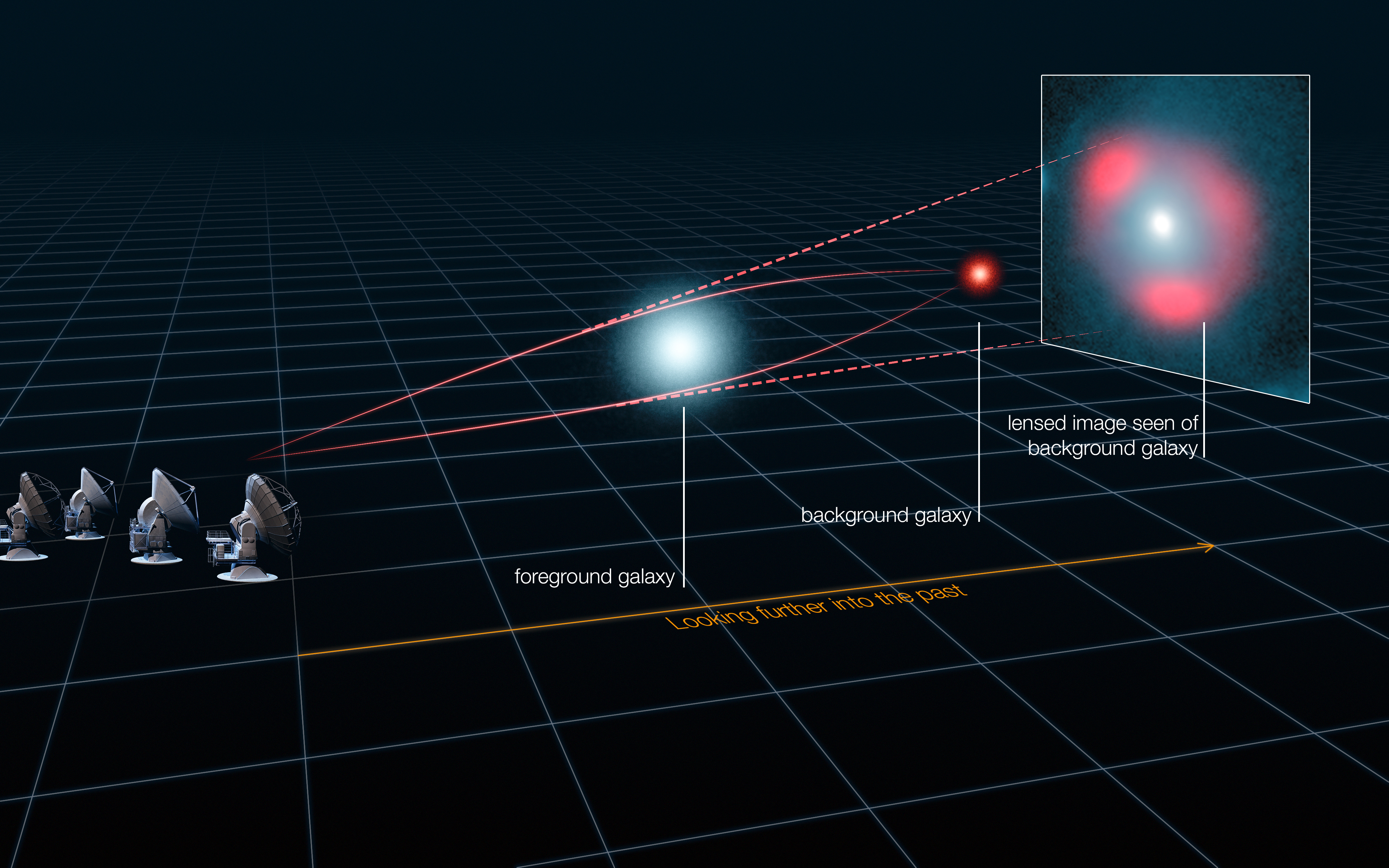

Another prediction of general relativity that Einstein published in the same 1916 paper was that during a Solar eclipse we should observe the positions of stars near the Sun to shift due to the bent paths that their light would take around the Sun. This same phenomenon, known as gravitational lensing, has since been observed countless times in situations where the light from a very distant galaxy bends around a massive foreground galaxy (see Figure 3-29). However, the first observation to confirm Einstein’s prediction took place during a 1919 Solar eclipse, during which the positions of background stars near the Sun appeared to shift outwards by precisely the amount predicted by general relativity. After this observation, both Einstein and his theories of relativity became world-famous.

General relativity is one of our most successful physical theories to-date, which has been confirmed by numerous important tests. While we are not able to discuss all of them here, before we do finish our discussion of general relativity there is one final test that is important to mention. General relativity is confirmed every day through its application in the Global Positioning System (GPS). General relativity predicts that not only space but time as well should be warped in the presence of massive objects. By astronomical standards, the Earth is not very massive, but its gravitational field does produce a small effect on the passage of time which diminishes with distance. GPS satellites are located at an orbital radius (measured from the centre of the Earth) roughly equal to three times the Earth’s radius. At that height, general relativity predicts that time should pass slightly more quickly. Roughly speaking, one second on Earth should be equivalent to 1.000000001 seconds on the GPS satellites. The difference may not seem like much, but this small error in time translates to an error of about 10 cm in positioning. And that 10 cm error, which would occur every second if general relativistic effects weren’t taken into account, is cumulative. This means that if general relativity weren’t accounted for, the error in the GPS signal would have been 10 km after only a single day of operation! So next time your phone gets you where you want to be, you can thank Albert Einstein.