Figure 3-13: A 1636 Portrait of Galileo Galilei. Source

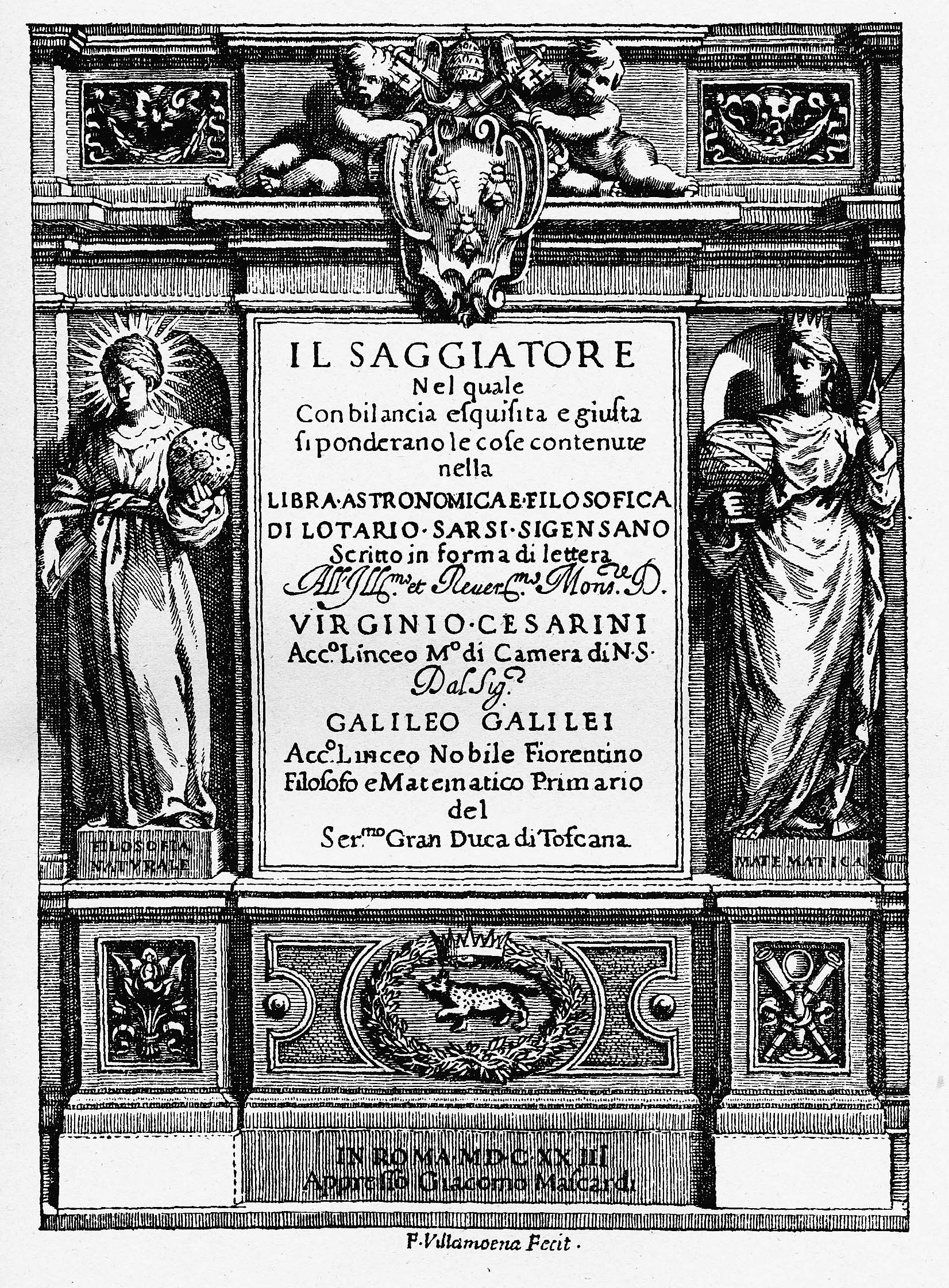

Galileo was a pioneer in experimental and mathematical physics, and for that work he is considered the father of modern science. His book The Assayer (see Figure 3-14), which was met with great acclaim, is now considered one of the pioneering works on the scientific method. In it, Galileo famously argued that experiment and mathematical formulation of scientific ideas should be upheld over reference to authority (i.e. to Aristotle). The Assayer was published in 1623, the same year that Galileo’s friend, Maffeo Barberini, became Pope Urban VIII.

Figure 3-14: Galileo’s Il Saggiatore (The Assayer). Source.

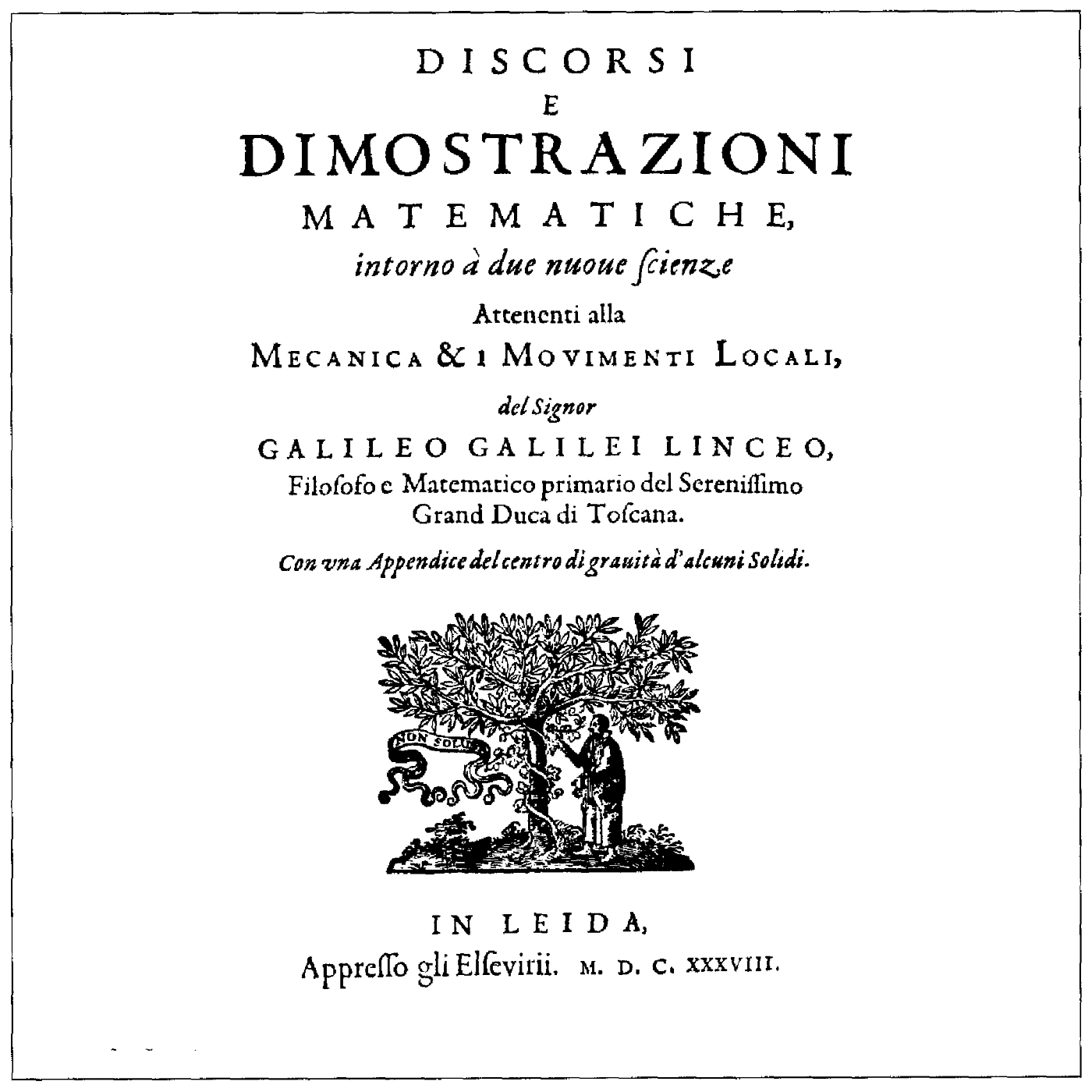

Fifteen years after he wrote The Assayer (i.e. in 1638), Galileo published his most influential attack on Aristotelian physics in his Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences (often simply called Two New Sciences, a book which laid out his work on motion over the course of thirty years; see Figure 3-15). In this book, he described numerous mathematical and experimental results that all went a long way towards demonstrating that the world was not as Aristotle described it. For instance, he described his experiments involving rolling balls of different masses down inclined planes, from which he was able to postulate that in a vacuum, or wherever air resistance and friction are insignificant, gravity will cause a ball to fall towards the Earth with constant acceleration that is independent of its mass. This conflicted with the teachings of Aristotle, who had said that everything falls at a constant rate, and that heavier masses fall more quickly than lighter ones.

Figure 3-15: Galileo’s Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences. Source.

In an unpublished book On Motion, which Galileo wrote fifty years earlier, he had already demonstrated that the Aristotelian idea must be false according to a proof by contradiction. Galileo imagined dropping two balls of unequal weight that were attached by a string. According to the Aristotelian idea, the heavier ball should fall more quickly until eventually the rope becomes taught and is subsequently slowed because it has to drag the lighter ball down with it. However, again according to Aristotelian physics, the combined system with two balls is heavier than either ball on its own, and should therefore fall more rapidly than either of its parts. Since the two conclusions contradict one another, Galileo concluded that the principles of Aristotelian physics they were derived from must be false.

In Two New Sciences, Galileo also discussed the law of inertia, furthering his discussion from his earlier Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632). He noted that a weight, dropped from the mast of a moving ship, will fall to the base of the mast since the mass and the ship have the same inertia in the horizontal direction, and the mass will move vertically with constant acceleration due to gravity. Similarly, he found that an arrow shot vertically from the ship’s deck will follow a parabolic arc, which he could describe mathematically as a consequence of the constant vertical acceleration due to gravity and the arrow’s constant horizontal speed (since the arrow must have the same inertia as the ship). However, he noted that from the perspective of anyone on the ship the arrow would appear to travel in the vertical direction only.

In this discussion, he made no mention of the implication that, hypothetically, the Earth could therefore be moving around the Sun—and with good reason. In the fifteen years since Galileo’s friend had become Pope and his arguments against basing science on the authority of Aristotle had been met with such acclaim, he had been tried by the Roman Inquisition, forced to “abjure, curse and detest” his opinions regarding heliocentrism, and the publication of any books he had written or ever might write had been banned. Indeed, Two New Sciences had to be published in Holland in order to escape this edict. Let us go back and discuss the series of incidents leading up to Galileo’s trial—his contributions to the heliocentric theory—which in fact began long before The Assayer.

The Galileo Affair

Galileo’s controversy with the Roman Catholic Church is as famous as the man himself, although the complex series of events that eventually led to his prosecution is often oversimplified. Galileo probably always held heliocentric sympathies, but for a long time he refused to publicly support Copernicanism. Indeed, when Kepler sent Galileo a copy of Mysterium Cosmographicum in 1597 (also sending copies to Tycho and others), the latter responded that he had accepted Copernicanism already several years before, but did not dare publish his reasonings and refutations for fear of ridicule. Kepler responded by urging him on (as, indeed, Kepler apparently had no fear of being a standard-bearer for the cause), but Galileo never responded.

It was only after the invention of the telescope that Galileo began making his views public. In 1609, he trained his telescope on the night sky and finally found what he considered to be sufficient evidence against the common beliefs that he no longer felt it prudent to hide his views. In March 1610, Galileo published a short treatise, Siderius Nuncius (Starry Messenger), with his initial findings that there are:

- mountains and craters on the Moon (he estimated that they are at least four miles high),

- more than ten times the number of stars that are visible to the naked eye, and

- four “stars” or “planets” (i.e. wandering stars; namely, Jupiter’s four largest moons) that appeared to be circling Jupiter.

Galileo’s lunar observations demonstrated that the Moon is not a perfect heavenly body, his discovery of numerous stars and star clusters was the first indication that the Universe is indeed far vaster than naked eye observations indicate, and the observation of Jupiter’s moons showed that not everything in the sky orbits the Earth.

None of Galileo’s observations exactly disproved the prevailing geocentric theory, but all of them would add greater support to the idea of imperfect, changing heavens, in which not all bodies orbit the Earth. Even so, he finally began to openly advocate for his heliocentric view—not explicitly in Siderius Nuncius, but in the events that followed. And while Galileo’s position did gain a following of supporters, the reaction was not all positive.

Galileo began bringing his telescope to parties and gatherings where other academics were present. These endeavours met with only moderate success, at best. Galileo’s telescope lacked stability, it was difficult to focus, and it had an extremely small field of view. For each of these reasons, it took great care to maintain a trained and focused view on any astronomical object. Furthermore, the telescope had only recently been invented after a chance discovery of the magnification potential of using lenses in combination, while the optical theory was still not understood. Sceptics who did bother taking a brief turn to look through the instrument either did not see the same as Galileo had during his many hours of observation, or they simply did not trust that the image was real and not produced by the telescope. Others simply refused to look through the telescope. You will explore the validity of this scepticism in the first lab.

The most important positive response came from Kepler, the respected Imperial Mathematician. Galileo sent him a copy of Siderius Nuncius with a request for review, and, without a telescope of his own that he could use to actually verify Galileo’s claims, Kepler enthusiastically obliged with an open letter that was widely published. Galileo was bolstered both by his discoveries and by this letter, and had a number of telescopes made which he sent to various patrons. Kepler had requested one in his open letter, but none were sent his way. Months later, Kepler wrote to Galileo again requesting some means of validating Galileo’s claims. In this letter, he voiced a concern that Galileo may have deliberately misled him. He noted the receipt of a number of letters claiming that Galileo’s published observations could not actually be seen through his telescope. But Kepler wanted to give Galileo the benefit of the doubt; therefore, making note of Galileo’s many claims to others that he had witnesses who would attest to the validity of the observations, he made a request for specific names. He also repeated his request for a telescope.

Galileo sent only a vague response. He thanked Kepler for his earlier support which he attributed to the latter’s “frank and noble mind” (Koestler, 1959). He wrote that “a good many” Italians had seen Jupiter’s moons, but were all hesitant to offer public support. He then made excuses about the difficulty of constructing telescopes that would equal his own. Despite the inadequacy of this response—the second of two letters that Galileo ever sent him—Kepler remained patient upon Galileo’s request that he await the publication of further observations.

Soon after, Galileo published one of the most important discoveries he had made with his telescope: he found that Venus exhibits a full set of phases similar to the Moon. From this observation, he could at last conclude that Venus must orbit the Sun.

Learning Activity

Review Figure 3-16 below: If what we see when we look at Venus is reflected sunlight, then if Venus’ epicycle were located entirely between the Earth and the Sun, as in the top figure, the side of Venus we see from Earth would never be more than half-illuminated. On the other hand, if Venus orbited the Sun, we would see it go through a full range of phases, as Galileo observed. What range of phases would you expect to see if Venus’ epicycle were located on the opposite side of the Sun?

Note that Galileo’s discovery did not disprove the Ptolemaic model. The radius of Venus’ deferent was not fixed in Ptolemy’s model, only the ratio of deferent and epicycle radii. In terms of reconciling Venus’ retrograde motion from the perspective of Earthly observation, the planet could have been modeled either as circling a relatively small epicycle moving around a nearby deferent, or as circling a larger epicycle moving around a further deferent. In fact, its deferent could even have been at the same distance as the Sun, with its epicycle causing it to go around the Sun, and this would have agreed with Galileo’s discovery. However, while there wasn’t a problem with the corresponding mathematical model, there was a problem with the Aristotelian physics of the old view: the Sun was supposed to be orbiting within a crystalline sphere centred on the Earth, and as Venus orbited the Sun in such a scenario, it would need to punch a hole in the sphere each time it went through.

Galileo soon observed sunspots as well:—dark patches moving across the surface of the Sun, which we now know to be relatively cool and, therefore, less bright areas of the Sun’s dynamic surface. Due to the relatively lower intensity of light emitted from sunspots, they appear dark. Like the surface of the Moon, the changing surface of the Sun presented a problem for the Aristotelian idea of the perfect and unchanging heavens.

Galileo also observed the rings of Saturn, although his telescope was not powerful enough to resolve them as such. He initially thought he was observing two smaller bodies on either side of the planet, making it a three-body system. This system also appeared to change, baffling Galileo. When Saturn tilted later in the year so that its rings were nearly edge-on from the perspective an observer on Earth, they vanished. When they reappeared later on, Galileo did not know what to make of them.

Kepler finally obtained access to one of the telescopes Galileo had sent out when one happened to visit Prague later that year. In September 1610, six months after he had first responded with his support, Kepler was finally able to publish his own independent observations of the moons of Jupiter.

While the number of independent confirmations of Galileo’s claims gradually emerged, opponents remained. In addition to the difficulty in actually confirming Galileo’s observations, a number of arguments from Biblical Scripture were brought forth which clearly stated that the Earth is at rest and the Sun moves. Galileo responded in the tradition of Biblical interpretation that had existed since the time of Thomas Aquinas, who had painstakingly merged the Bible with the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic worldview. Galileo’s argument was that in these instances, the Bible should not be taken literally as it was meant to relate to the relative perspective of Earthly observers. This would mark the beginning of Galileo’s troubles with the Catholic Church.

Through his struggles Galileo did manage to gain supporters; but his open ridicule of any who did not see what he had seen also found him many strong opponents. And when word got out of Galileo’s claim that the Bible should not be taken literally, those opponents took the matter to the Church with charges of heresy. In 1616, Galileo finally went to Rome to plead his case against these detractors. The verdict: while it was all right to employ a heliocentric model for the purpose of “saving the appearances”—i.e. if it led to a more accurate description of celestial motions—the heliocentric principle, that the Sun actually lies at the centre of the Solar System and that the Earth orbits around it, stands contrary to Scripture and is therefore not to be held or defended. In fact, not only was Galileo forbidden from holding or defending Copernicanism, but the trial led to Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus being suspended until certain passages could be corrected.

Now, it is important to recall our previous discussion about Kepler and the way he always worked to confirm whatever physical principle he believed in. Indeed, without the hypotheses he made that guided his work, it is very likely that Kepler never would have accomplished all that he did. In many ways, the requirement that science should merely be used to “save the appearances”, which denies the scientist the ability to speculate about the (ultimately unknowable) foundations of their theory, cuts science off at the knees. Physics has often made the greatest progress when physicists were given the freedom to creatively approach physical problems.

However, as things stood, Galileo could say little more on the matter of heliocentrism. He held his silence until after Urban VIII became Pope in 1623. That year, Galileo travelled to Rome again to congratulate the Pope, who had showed particular favour for Galileo’s ideas and had opposed the decision of 1616. Urban VIII encouraged Galileo to write the arguments for and against heliocentrism in a book, ensuring that he did not advocate in favour of the hypothesis. The result was Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, published in 1632 with formal authorisation from two Inquisition censures and the Pope himself (see Figure 3-17). In fact, Urban VIII even made a request that Galileo include somewhere in the discussion one of his own favourite arguments. The argument was that because of God’s omnipotence, He could in fact have constructed the Universe any way at all while making it appear to have a different form, and thus observation alone could never be enough to determine its true nature.

Within months of the Dialogue’s publication, Galileo was called to Rome to defend himself against the Inquisition. In light of the Papal support and censure that the Dialogue had received prior to publication, it may be surprising that events proceeded as they did. In the end, there were two basic reasons that allowed Galileo’s enemies to succeed once more. Galileo’s Dialogue is a four day-long discussion between three characters: Salviati, a quick-witted defender of Copernicanism; Sagredo, who is as intelligent, but is uninformed; and Simplicio, a dimwit who defends the Ptolemaic model by making all the old arguments, which are overturned one-by-one. The reason Galileo found himself brought up on charges is that he placed the Pope’s argument in the mouth of Simplicio; therefore, when his enemies pointed out what he’d done, Galileo lost the Papal support he would have had at his defence. And the reason he was found suspect—and ultimately guilty—was that the Dialogue so obviously argued for the Copernican view that no reader could reasonably doubt that the author’s intent was indeed to defend the view. Therefore, Galileo had violated the 1616 order to not hold or defend the heliocentric view.

On 22 June 1633, Galileo was found “vehemently suspect of heresy” and ordered to “abjure, curse and detest” his opinion that the Sun lies motionless with the Earth orbiting around it, and that one may hold and defend this opinion as probable when it had been declared contrary to Holy Scripture. As he did this at the age of 69, on his knees before the Inquisition, legend has it that Galileo rose whispering “and yet it moves”. He was ordered to house arrest for the rest of his life, and every book he had or ever would write was banned. He managed to have Two Sciences published in Holland, where the Roman Catholic Church held less sway.

Both Galileo’s Dialogue and Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus were removed from the Catholic Church’s Index of Forbidden Books in 1835, following formal legal proceedings which finally determined that books openly treating heliocentrism as a physical fact were acceptable. This resolution came 150 years after Isaac Newton had pulled together the pieces from works by Kepler, Galileo and others in order to develop his great theories of mechanics and gravitation.

Now, before turning to a discussion of Newton’s achievements, it is worth pausing to clarify something. In retrospect, it is often all too easy to pass judgement on those who refused to see what the revolutionaries saw. However, it has also rarely been the case that the revolutionaries actually had everything sorted out correctly—and in that regard one should not be too hasty in jumping to their support. Indeed, as we’ve already seen, Kepler’s ideas about the Universe were completely wrong. Therefore, although his three laws were accurate, it would indeed have been challenging for any of his contemporaries to know where the line should be drawn between those and the background of planetary spheres, Platonic solids and celestial harmonics. Similarly, Galileo’s ideas about the world were not free of error. For one thing, he always maintained that the planetary orbits must be circular (in fact, he never acknowledged any of Kepler’s work). And although he had understood inertia better than the Aristotelians, he still managed to convince himself that the circular orbits of planets should somehow also be inertial, which Newton eventually showed to be false. Yet another explanation that Galileo got completely wrong was that of tides, as we’ll note when we come to Newton’s explanation.