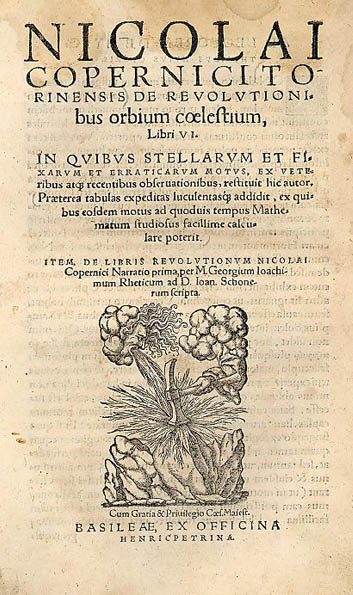

In Module 2, we explored seven centuries of immense progress in human understanding, during which people began actively seeking a scientific explanation of celestial phenomena. In fact, they not only sought the explanation, but, as they had inherited no prior rubric describing how to do this, they also needed to define the parameters of how to do science. They understood that hypotheses were necessary, and many were proposed and logically analysed. After Alexander the Great had united much of the Western world—from Greece to India, and down into Egypt—the newly founded Alexandria became a hub of knowledge, where many of the greatest scholars throughout the empire went to study. The final product of Alexandrian astronomy, and the culmination of the ancient Greek exploration of the cosmos, was Ptolemy’s Almagest. In the history of astronomy, Copernicus is Ptolemy’s direct descendant, despite the fact that fourteen centuries separate Ptolemy’s Almagest from Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus.

After seven centuries of cosmological and astronomical exploration, twice as much time passed without another significant advance, despite the fact that Ptolemy had gotten things all wrong. Why was no more progress made? Did everyone just assume for 1400 years that Ptolemy had to be right? Someone must have questioned Aristotle’s physics or Ptolemy’s model: were they all branded as heretics and burned at the stake? A naïve look at the history of (lack of) developments and at some of the events that took place during the Scientific Revolution might lead you to believe that the answer to the first question is that “progress halted because the answers to the second and third questions are in fact ‘yes’ and ‘yes’.” However, this conclusion would be all wrong.

In order to properly understand Copernicus’ place in the history of astronomy, we need to look at more than just the details that were known to astronomers—viz., the descriptive strengths and weaknesses of Ptolemy’s model, along with the assumptions it built from which one might have contrasted with alternative hypotheses, etc. While these details are certainly important to the question of why no significant advance was made in astronomy for 1400 years, it really is more important to note the changes that took place in the priorities of astronomers. From the era in which Greek philosophy flourished, until after Copernicus, that curiosity about the world that motivated Thales in the sixth century BCE to begin searching for a rational explanation of Nature hardly existed among scholars. Indeed, as we’ll see, Copernicus himself did not fall into the same tradition as Thales, though he inspired others like Galileo and Kepler who did.

In fact, when we look more closely it appears that even a general interest in astronomy and physics progressively waned, so that both Ptolemy’s and Aristotle’s works were lost in Europe in the course of the Dark Ages. Their works were recovered in time, but the process of rediscovery was not instantaneous, and began only a few centuries before Copernicus was born. Already this extra bit of information tells us how wrong we would be to suppose that scholars had been married to the ancient texts for over a millennium; on the contrary, there was hardly any interest in them at all. Even when many of the ancient texts had been recovered, the priorities of those who inherited them bore almost no resemblance to those of Thales or Aristotle.

We are currently living in an era of unprecedented scientific progress. The advances that were made over the past century towards a better understanding of both the large (cosmological) and small (quantum) scales in nature outweigh any that came before. The shift from an Aristotelian picture to the universe described by Newton comes in as a distant second to the shift that has occurred since the turn of the twentieth century, to a description of nature that we are still grappling to fully understand. From this perspective, it is challenging to understand or appreciate a society that was not inquisitive about nature and did not value creative thought and exploration in search of nature’s best explanation, yet it is precisely such a society that spans the time from Ptolemy to Copernicus. Understanding this is the key to understanding not only why no major innovation took place in astronomy for 1400 years, but also why events transpired as they did during the Scientific Revolution.

In fact, the degradation of cosmological inquiry began long before Ptolemy. When Alexander the Great united his empire and created Alexandria as the hub of ancient knowledge, scholars from diverse cultures came together to share their knowledge. As discussed in Module 2, the science they produced was less philosophical, and tended to concentrate more on mathematics and the collection of accurate data. Alexandrian science achieved a great deal—from Euclidean geometry, to the Hipparchan tradition in astronomy that eventually led to the Ptolemaic model—but it came at a price: its astronomical product was wrong, and the astronomers who produced it cared little for, and largely neglected, alternative hypotheses/philosophies like that of Aristarchus.

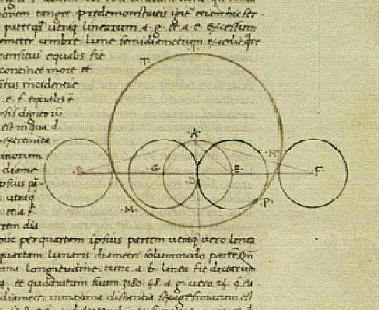

In short, philosophers like Aristarchus who concerned themselves with “the true nature of reality” and sought a rational system to explain the phenomena were too few, and too far between to have had much influence on subsequent developments in astronomy. The mathematical systems that the Alexandrian astronomers devised to describe the motion of the planets were mainly geometric constructs that were not even intended to resemble any hypothetical physical reality. For instance, in Module 2 it was noted that in order to accurately describe the Moon’s position in the sky, Ptolemy had to use an epicycle so large that the Moon’s angular diameter would need to vary far more than it actually does; therefore, when Ptolemy approached the problem of calculating the Moon’s distance, he used a different epicycle. Astronomy was not required to be “right”; its models only needed to be accurate, and could even adapt to suit specific purposes.

From the perspective of developing a geometric model that was not intended to be realistic, just accurate, Ptolemy’s model was sufficient. And it remained sufficient only as long as people were not concerned with finding a realistic, rational model of the cosmos that would consistently fit in with a comprehensive physical description of nature. That feat was first achieved by Newton, and came after roughly only a century of searching. This number—just one century—is much less than the fourteen that separate Ptolemy from Copernicus. In contrast to our original question of why it took so long for Ptolemy’s system to be challenged, you might wonder whether, if Ptolemy’s immediate successors had just stuck with the problem, could they have arrived at Newtonian physics in just a century? The answer, of course, is “No: there were a number of important advances that took place in the centuries leading up to the Scientific Revolution, without which Newton’s achievement would not have been possible.”

There are too many details that must be considered for us to provide a comprehensive explanation here of why Ptolemy went unchallenged for 1400 years; in fact, you should be starting to appreciate that the explanation is not all that simple. If you have further interest in the topic, there is an excellent chapter in Thomas Kuhn’s The Copernican Revolution, which is included in the list of Supplementary Resources for this module. In contrast, we review the details only briefly here before moving on to consider Copernicus’ work. Our goal will be simply to show that there was no millennium-and-a-half tradition of Aristotelian physics and Ptolemaic astronomy in Europe, no systematic oppression of proposed alternatives that Copernicus ever felt a need to fear; thus, we will set the stage for a discussion of Copernicus’ work and its consequences.