The earliest astronomers from every part of the world knew that—in addition to the daily rotation of the celestial sphere about the Earth:—the stars shift their positions at a given time very slightly each day; the Sun moves through the zodiacal constellations annually; the Moon moves through the zodiacal constellations monthly; and the planets wander through the zodiacal constellations, occasionally exhibiting retrograde motion. In fact, the word “planet” comes from the ancient Greek word meaning “wandering” star, and the paths of these wandering stars were unquestionably the most difficult to describe.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that science was born out of human interest in the night sky, and in particular from the single objective of wanting to describe the motion of the five wandering stars—the planets. The first scientist to arrive at an acceptable description was Ptolemy, but his work would not have been possible without the work of earlier astronomers, particularly Hipparchus of Nicaea (c. 190—c. 120 BCE), who made the greatest advances in astronomical measurement of anyone who came before him.

One reason why observational records like Hipparchus’ were so important is that astronomical phenomena are very slow to occur. When we look up at the night sky, despite the fact that the Earth is actually spinning quite rapidly, the stars do not move at a perceptible rate. From one night to the next, the Moon moves a noticeable amount with respect to the stars, but the Sun moves only about 1° along the zodiac every day (360°/year), so the night sky does not appear to change on a daily basis. The equinoxes—where the Sun’s annual path along the ecliptic intersects the celestial equator (the projection of Earth’s equator onto the celestial sphere)—occur only twice a year, and the retrograde loops of Mars, Jupiter and Saturn occur less than once a year. Perhaps the greatest achievement of Hipparchus, who is credited as the founder of trigonometry, was his discovery of the precession of the equinoxes—a phenomenon with a period of 26,000 years.

The equinoxes and their precession are best understood correctly—i.e. in a heliocentric picture. If explained that way, the phenomenon that Hipparchus observed is easy to describe. The alignment between Earth’s orbit and its rotational axis, and the relation to the seasons, were discussed in Module 1; but it is useful here to briefly review. The Earth’s rotational axis is tilted 23.5° from its orbit, and the direction it points in space does not change as it makes its way around the Sun. Winter solstice occurs when the north pole points 23.5° away from the Sun, and summer solstice occurs when the north pole is pointed 23.5° towards the Sun. Because Earth’s rotational axis always points in the same direction, the stars maintain fixed positions on the rotating celestial sphere. In particular, the celestial equator is constant. Because of the Earth’s tilt, the Sun does not travel along the celestial equator, but along the ecliptic through the zodiacal constellations. It is only when the Earth’s rotational axis is tangential to its orbit that the Sun intersects the celestial equator. These two points are called the equinoxes, and they occur twice a year, roughly halfway between the solstices (see Figure 2-3).

The Earth’s rotational axis is not actually precisely fixed: it wobbles very slowly, with a period of roughly 26,000 years. This means that the celestial sphere is also slightly wobbling, and that the Sun’s position with respect to the “fixed” stars shifts very slightly from one vernal or autumnal equinox to the next. The thing we now know to be actually happening is that the Earth is wobbling like a top, and the phenomenon that we observe as a consequence of this—the shadow that is cast on the back of Plato’s proverbial cave—is that the Sun does not cross the celestial equator at precisely the same two points every year.

The change is almost imperceptible: the Sun’s location in a given month has shifted by roughly one constellation in the past two millennia. (As a consequence, astrology today does not actually follow the zodiac, since it’s never been updated). The equinoxes move westward along the ecliptic as a result of the Earth’s wobble, and the phenomenon was historically called the precession of the equinoxes because the Sun’s intersection with the celestial equator is an event that could be accurately measured. Using data that had been collected over two centuries, Hipparchus found that the rate of precession of the equinoxes was no more than 1° per century, and that the period of precession was therefore no more than 36,000 years.

Learning Activity

The precession of the equinoxes is a good example through which to think about the logical structure of science. Take a moment to reflect on the observations that are made. The stars in the celestial sphere rotate about the Earth every day, and every day the Sun moves about 1° along the ecliptic. The north and south poles of the celestial sphere remain fixed, while 90° from them is the celestial equator, which makes the largest concentric arc. As the Sun makes its own circuit through the zodiac, it intersects the celestial equator twice a year. Through very careful observations you could notice that those two points are not the same from one year to the next. As a scientist, your approach at this point could go along any of three directions. First of all, you need more precise measurements, and you want to observe as much variability as possible. Secondly, you need an idea of what is causing the phenomenon to occur. And thirdly, you need to use that idea in constructing a mathematical description—a model—that can be compared against observations.

In the case of precession, you will need to collect data over the course of centuries, since the annual amount of precession is so small as to be imperceptible—in fact, it’s about as much as a star moves in 2 seconds. With precise measurements separated by 100 years, the problem becomes like measuring how far a star moves in 3 minutes, which is more manageable—e.g., that is the change measured by Hipparchus. To get an idea of how precise Hipparchus and his predecessors needed to be with their measurements, the next time you are out at night cup your hands around one eye and see if you can detect any motion in the stars by focusing on one and watching it in this way for a few minutes. Hipparchus measured a similar angular shift in the second century BCE; but he had to rely on the precision of already centuries-old data, and he had to be certain that he and his predecessors had accurately accounted for the timing between whatever they were measuring and the vernal equinox.

Now, given the astonishing feat of having actually measured this change, your next step would be to find a mathematical model that describes how the change will progress into the future. You could begin with an idea of what is going on, work out the corresponding mathematical description, compare with existing data, and wait for new observations to confirm the model’s predictions.

It is easy to get lost thinking about all the sticky details of how you would accomplish each of these things effectively. Just a few of the challenges that scientists from Hipparchus to Hawking have taken up, are:

- coming up with the right basic idea to explain observations, knowing that we may never be certain that it is the right one, and working out all the mathematical details of what it would describe;

- thinking up novel things to look for, as spatially and temporally limited observers, and making precise measurements; and

- comparing these limited and imperfect observations with the predictions of multiple hypotheses, to determine which one fits the best.

As you consider this, try to think of how one might go about determining the cause of the precession of the equinoxes: perhaps you would think it best to concentrate first on developing an empirical model.

In addition to measuring the precession of the equinoxes, Hipparchus also used ancient records along with his own observations to determine values for the lunar month and solar year, which were off by less than a second and by 6 minutes, respectively, from the true values. He adopted Eratosthenes’ value for the Earth’s radius, RE, as his unit of distance and found the Moon’s radius and distance to be 0.29 RE and 60.5 RE (actually 0.27 RE and 60.3 RE), respectively. He estimated the Sun’s distance at 2550 RE (actually, 23,000 RE; but Copernicus’ value was worse, at 1142 RE), although he was not able to observe a solar parallax.

Hipparchus’ models for the motion of the Sun and the Moon were based upon the previous work of Apollonius of Perga (c. 262—c. 190 BCE). It had long been known that the apparent speeds of the Sun and Moon are not constant, and Apollonius found two mathematically equivalent ways of describing the phenomenon which were in keeping with the principle of uniform circular motion:

- If the Sun and Moon moved uniformly along circular orbits with the Earth offset from centre (a point called the eccentric), then their speeds would appear to vary as they went around; or,

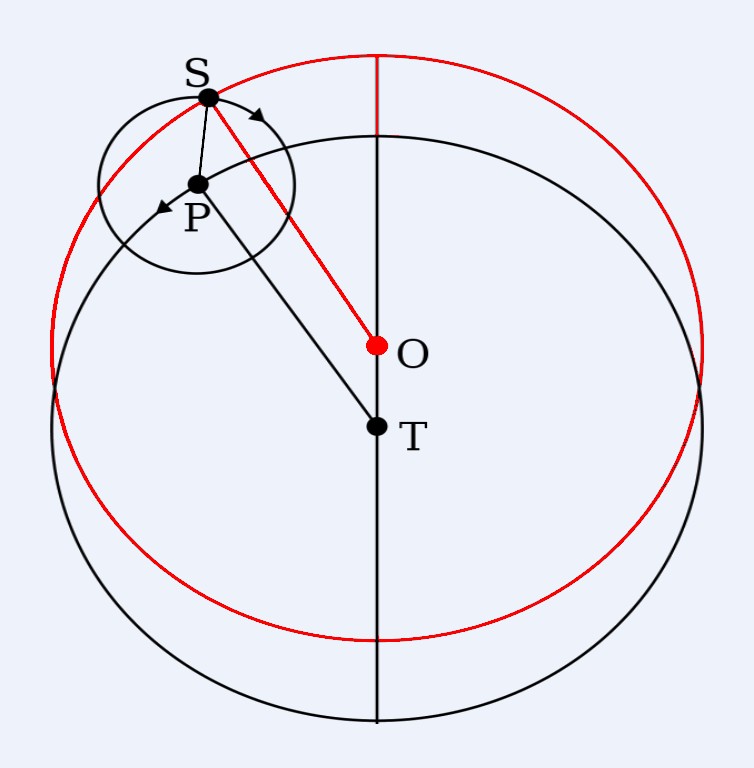

- If the Earth were at the centre of a circle, called a deferent, and if the Sun or Moon orbited uniformly around a second circle, called an epicycle, whose centre moves uniformly around the deferent, their paths would in fact be the exact same as if they followed the eccentric orbits of hypothesis i (see Figure 2-4).

Figure 2-4: The equivalence of deferent-and-epicycle and eccentric orbits. (a) The orbit of S around T (the red circle) can be described equivalently as a circle centred about O, from which T is eccentric, or as the path traced out by S as it moves uniformly around an epicycle that moves uniformly along a circular deferent that is centred on T. Source.

Apollonius’ theorem proves a marvellous equivalence. It also provided exceptional utility for describing the orbits of the Sun and Moon. Hipparchus’ model was able to represent the Sun’s apparent motion to within an error of 1’, and although the error in his model of the Moon’s position could be as much as 2.7°, it generally provided a very accurate description as well. In order to describe the apparent paths of the Sun and Moon from Earth’s eccentric position, Hipparchus invented trigonometry. Thus, he was able to capture the variable speeds of the Sun and Moon through the celestial sphere, using a model that was consistent with the principle of uniform circular motion, and therefore with the apparent motion of the stars.

Despite Hipparchus’ meticulous measurements of the planets’ positions, he failed to find an accurate model to describe them. Even so, we can easily imagine how he must have viewed the problem. He had found a reasonably accurate model to describe the apparent motion of the Sun and Moon which indicated that their variable speed through the zodiac could be explained by a deferent-and-epicycle model which shifts their circular paths so that the Earth is at an effectively eccentric position. In these models, the epicycle turns in the direction opposite its motion around the deferent. In contrast, Mercury and Venus appear to follow the same path as the Sun, circling around epicycles that turn in the same direction as, and more quickly than the epicycles move around their deferents—they appear to orbit around the Earth, clearly rotating about some central point as they do so. We now know that the Sun is (roughly) at the centre of Mercury’s and Venus’ orbits, and that the cause of their apparent prograde and retrograde motion is that they are actually orbiting around it; but as far as Hipparchus knew the centre of their epicycles could have been anywhere on the line connecting the Earth and the Sun. Thus, Mercury’s and Venus’ orbits were similarly thought to be describable through a deferent-and-epicycle model.

At this point, only three celestial objects remain: Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. These three planets mostly move in one direction along the zodiac, except for every year-and-a-bit when they follow a retrograde loop that looks a lot like the more frequent retrograde loops of Mercury and Venus. Therefore, Hipparchus supposed that these three planets should also follow deferent-and-epicycle orbits, both turning in the same direction, but now with a frequency of rotation along the epicycle that is less than the frequency of the epicycle’s orbit around the deferent; thus, a little less than once a year the three planets would apparently pause, and reverse direction a little while, as their epicycles drew them to their closest distances from the Earth.

In fact, this last point—that Mars, Jupiter and Saturn are the closest to the Earth while exhibiting retrograde motion, and furthest away at the opposite point on the deferent—is both true and in keeping with further empirical evidence: these three planets are the brightest when their retrograde motion occurs. In the heliocentric theory, this phenomenon is explained because retrograde motion is supposed to occur due to parallax when the Earth comes closest to these three planets every year-and-a-bit. And the reason for the “and-a-bit” is that the planets themselves are also orbiting the Sun, so the Earth has to complete more than one full orbit before it comes in line again. In the geocentric theory, the phenomenon was explained because Mars, Jupiter and Saturn were thought to follow deferent-and-epicycle orbits.

At this point in our discussion, it is worth highlighting an important aspect of the geocentric model: it provided a self-consistent explanation of many different facts that were not obviously connected, through a few key principles that were taken as well from observation. The epicycle-and-deferent model could be used not only to describe the continuously looping motion of Mercury and Venus, but could explain the retrograde motions of Mars, Jupiter and Saturn as well, and in so doing it also explained why they are the brightest when going backwards along the ecliptic. It even entered into the description of the Sun’s and Moon’s orbits, through the equivalence with the eccentric model, despite the fact that the Sun and Moon exhibit no retrograde motion. Finally, the model was in keeping with the principle of uniform circular motion, derived from the daily motion of the celestial sphere—a motion which appeared so different from the apparently natural tendency of terrestrial substances to rise or fall vertically.

Einstein (1994; p. 309) famously wrote that “the grand aim of all science…is to cover the greatest possible number of facts by logical deduction from the smallest possible number of hypotheses or axioms,” while “the observed fact is undoubtedly the supreme arbiter.” And for this reason, Hipparchus must be considered as great a scientist as anyone before or since, as his many accomplishments certainly met this aim.

Along with his development of accurate models describing the motion of the Sun and the Moon, for which he invented trigonometry, Hipparchus catalogued the positions and apparent brightnesses of some 900 stars. In fact, the apparent magnitude system we still use to describe the brightness of astronomical objects is based on Hipparchus’ system. While the problem of accurately describing the planets’ motions would be left open, it would be another 300 years before astronomy made another significant advance.