The Sun rises in the east and sets in the west, as with every other star. This motion results from Earth’s daily rotation. In addition to this daily motion, however, you are probably also aware that the Sun reaches a much higher altitude in the summer than it does in the winter. While the stars on the celestial sphere make the same arc across the sky every day when viewed from any location on Earth, the Sun apparently rises up through them until the summer solstice is reached, marking the longest day in the year when the Sun reaches its maximum altitude as it crosses the celestial meridian. After the summer solstice, the Sun gradually drops down through the celestial sphere, eventually making its way to the winter solstice—its lowest point on the celestial sphere—on the shortest day of the year.

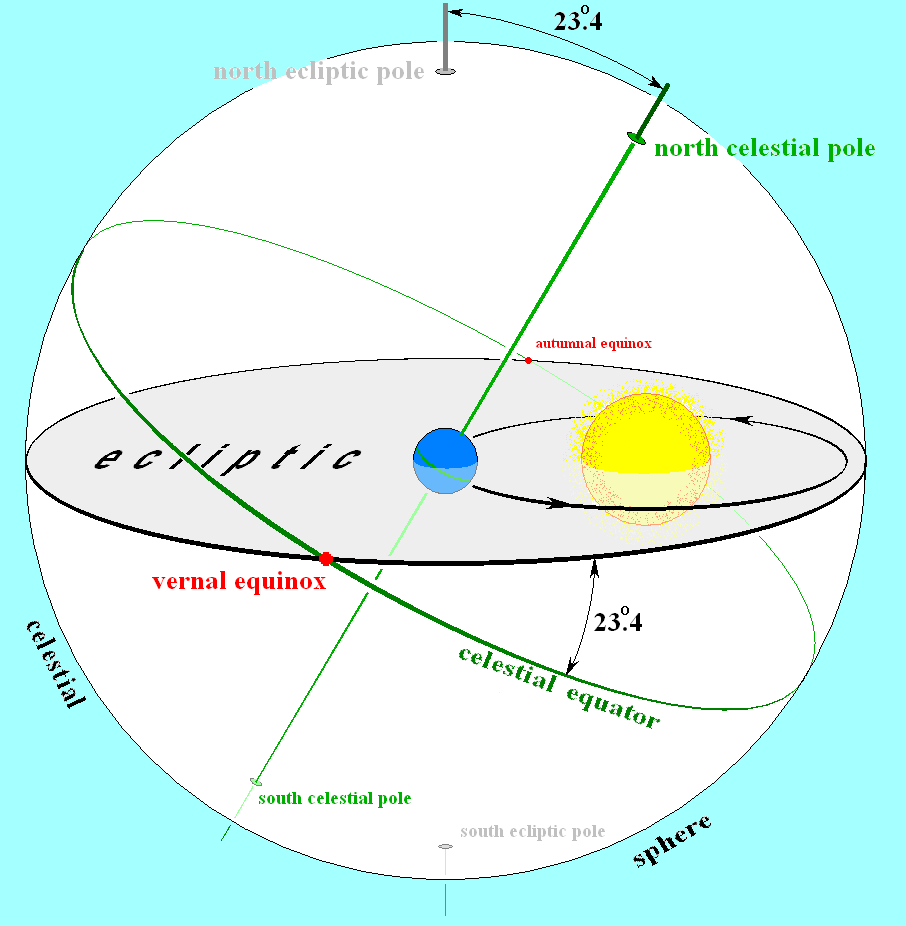

While the Sun makes its way from the summer solstice to the winter solstice, it does not remain at the same right ascension, but in fact moves through twenty-four hours of right ascension in a year. The reason for the Sun’s annual motion is that the Earth’s rotational axis it tilted 23.4° relative to its orbital plane. Study Figure 1-5, which simultaneously illustrates how Earth’s daily rotation defines the celestial sphere and how Earth’s annual revolution around the Sun defines the ecliptic, thus explaining why the celestial equator and the ecliptic do not coincide.

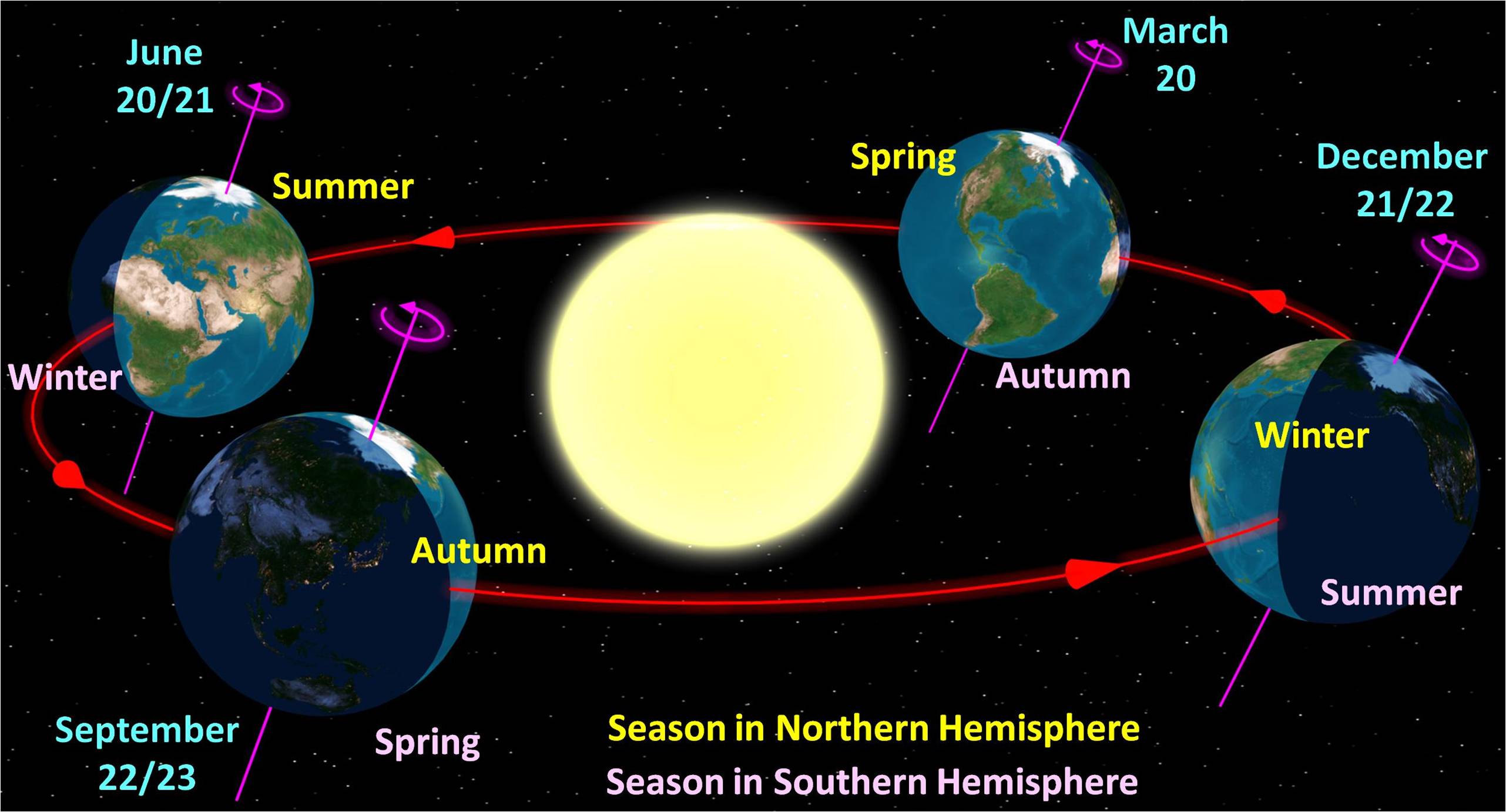

There are four configurations of note in Figure 1-6. First, the configuration of the Earth and the Sun shown in the picture is the configuration at the summer solstice in the northern hemisphere, when the Sun reaches its highest angle 23.4° above the celestial equator. A half a year later the Earth is on the opposite side of the Sun, the northern hemisphere is tilted away from the Sun, and it is the winter solstice in the north. One-quarter of a year after that, the Earth is behind the Sun so that the Sun is projected onto the vernal equinox. On the vernal equinox, the line between the Earth and the Sun is perpendicular to the Earth’s axis of rotation, so its tilt does not affect the apparent position of the Sun on the celestial sphere and the ecliptic coincides with the celestial equator. In other words, the vernal equinox occurs when the Sun is at the zenith when viewed from the equator. Half a year later, another equinox is reached, called the autumnal equinox.

With these explanations of the solstices and the equinoxes, we finally come to an explanation of why there are seasons on Earth. The essential point is that summer occurs in the hemisphere that is tilted towards the Sun and winter occurs in the hemisphere that is tilted away from the Sun. It is the Earth’s changing orientation relative to the Sun throughout the year that causes the seasons. This occurs as a result of two simultaneously reinforcing factors.

As with the solstices and equinoxes, the effect of the Earth’s orientation relative to the Sun on the heating of the Earth is best explained through a diagram. Therefore, please refer to Figure 1-7. As the diagram shows, incident sunlight that reaches the Earth at more oblique angles must be spread out over larger areas. Therefore, the same amount of sunlight goes into heating a larger area when the Sun is low on the horizon than when it is more directly overhead. The more concentrated sunlight there is on a given area, the more that area will be heated. Furthermore, when the Sun appears low on the horizon its light must pass longer distances through the Earth’s atmosphere than when it is directly overhead, with a greater likelihood of being scattered and not reaching/heating up the Earth’s surface.

This concludes our explanation of why the seasons occur on Earth, as an effect due to the tilt of Earth’s rotational axis relative to its orbital plane. You may find it helpful to reinforce the explanation by watching the following video from Bill Nye the Science Guy: