As noted earlier in the module, the celestial sphere is a two-dimensional evolving map of all the stars, planets and other objects in our night sky. During the day, sunlight is scattered by the atmosphere. This scattered light is randomly redirected, illuminating the sky along with the rest of the world around us. (The sky scatters blue light most effectively, which is why the sky is blue in the daytime). At night, sunlight is blocked by the Earth and doesn’t reach the atmosphere above us. This is why at night we see the dimmer light from objects fainter than the Sun, such as stars, shining through the atmosphere. Even so, it is possible to map the permanent locations of every star on the celestial sphere regardless of whether they are visible or not.

In order to create this map, however, coordinates need to be defined. Astronomers commonly use both subjective and objective sets of descriptors. Subjectively, we define:

- the horizon as the lowest point in the sky that is visible from a given location

- a star’s altitude as its angle above the horizon

- the zenith as the point in the sky directly overhead, at an altitude of 90°

- the celestial meridian as the line connecting the north point on the horizon (found with a compass) with the south point on the horizon through the zenith

- a star’s azimuth as its angular distance from the northern celestial meridian, measured towards the east (see Figure 1-2).

Subjective descriptors of the celestial sphere depend on both the observer’s location on Earth and the time of their observation. They are useful in practical astronomy, both when describing the locations of objects in one’s own night sky and when comparing observations between two locations.

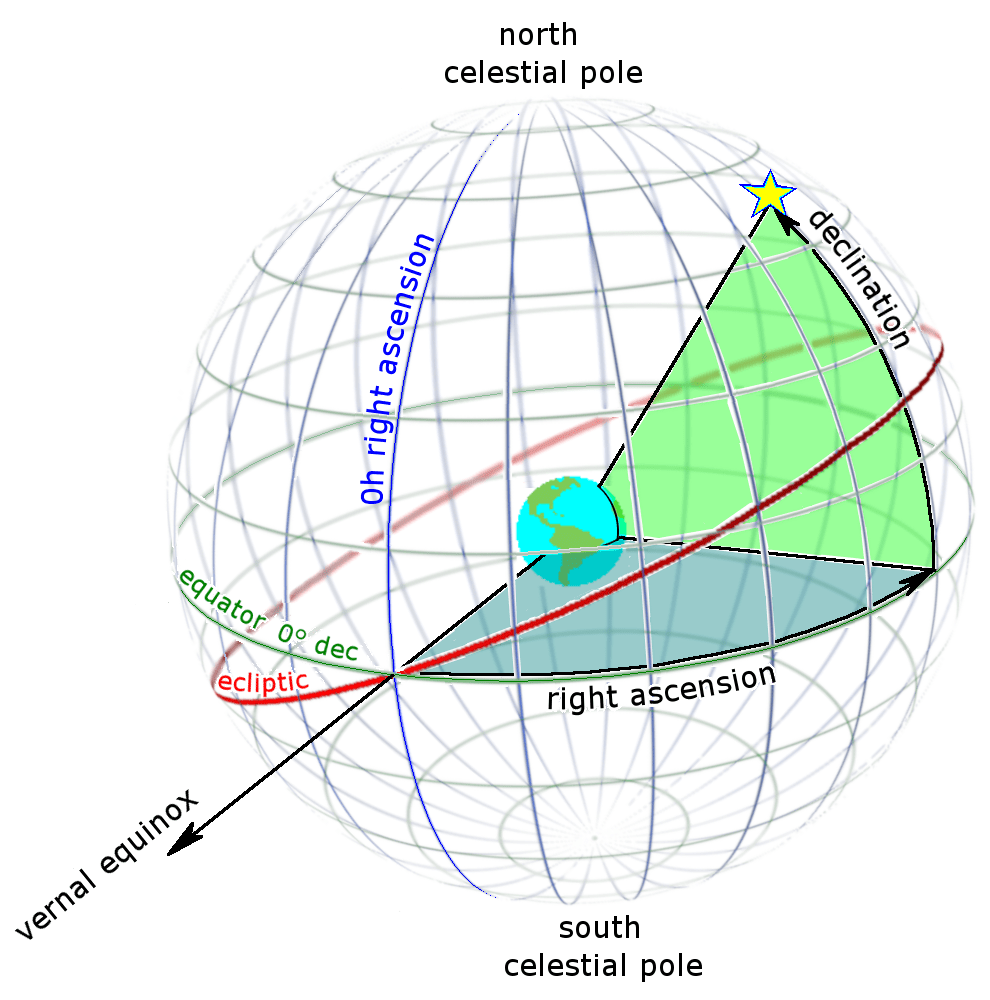

It is also useful to define an objective set of coordinates that cover the celestial sphere and are independent of observer location or observation time. (For visual aid, you may find it useful to refer to Figure 1-3 as you read through the definitions of these coordinates.) These are similar to latitude and longitude coordinates on a globe, which are defined according to international standards, whereas the subjective descriptors are more akin to “right here” or “100 metres down the road in that direction.”

According to the objective description, the stars should all hold their coordinate position both throughout the day and throughout the year. This is done by projecting the Earth’s North and South Poles onto two points on the celestial sphere known as the celestial poles. Then, the Earth’s equator also projects to a great circle on the celestial sphere known as the celestial equator. The distance between the celestial equator, like the latitude angle on Earth, is measured in degrees. The coordinate angle describing this angle is called the declination. The celestial equator has a declination of 0°, the north and south celestial poles are at +90° and -90° declination, respectively. While a star might rise above the horizon to a certain peak altitude (when it reaches the celestial meridian), its declination describes its constant position on the revolving celestial sphere. In order to be precise in stating a star’s position, astronomers use the convention of stating its declination in degrees (°), arcminutes (’) and arcseconds (’’). In this convention, 1° = 60’ and 1’ = 60’’ (therefore, 1° = 60’ ⋅ 60’’/1’ = 3600’’). Typically, positions on the celestial sphere are given to tenths of an arcsecond; e.g., the declination of Vega is +38° 47’ 01.3’’.

As with geographical locations specified by latitude and longitude, positions on the celestial sphere require a second coordinate to be specified. We will define the celestial sphere’s analogue of geographical longitude, known as right ascension, below; however, before we do that we can already develop a better sense of how declinations and the daily motion of the celestial sphere relate to one’s geographical location.

Learning Activity

As you read through the remainder of this section, try turning your body to face the indicated directions, pointing your hand and drawing lines across the sky as you orient yourself within the celestial sphere. In this way, you will develop a visual understanding of the apparent celestial motions that are being described. You may also wish to grab a pen and paper so you can sketch the positions and angles at which the celestial objects are oriented. Before you begin, determine which direction is north, using a compass if you require. For the purpose of illustration, we will assume you are located in Saskatoon, at a latitude of 52° N.

Given that your latitude is 52° N, and that the celestial equator is the projection of the Earth’s equator onto the celestial sphere, your zenith (i.e. the projection of your position onto the celestial sphere) must be 52° along the celestial meridian north of the celestial equator. Since the north celestial pole is 90° north along the celestial meridian from the celestial equator, the north celestial pole must therefore be (90° – 52° =) 38° north of your zenith along the celestial meridian. Furthermore, since your zenith is 90° above the north point on the horizon, this means that the north celestial pole is at an altitude of (90° – 38° =) 52° above the north point on the horizon.

Now recall that the north celestial pole does not move. As the Earth rotates, the celestial sphere appears to revolve around us. The following time lapse video shows the motion of the stars surrounding the north celestial pole.

In the video, the star closest to the centre which moves the least is Polaris (α Ursae Minoris), the north star. For an observer in Saskatoon, Polaris, along with every star within 52° of it (i.e. every star above a declination of +38°) never sets. These stars, which circle the pole, are known as circumpolar stars. In contrast, turning our attention towards the south point on the horizon, it should be apparent that there are stars which are never visible from Saskatoon. Specifically, recalling that the celestial equator (declination 0°) reaches an altitude of 38° above the southern horizon at the celestial meridian, we find that any star below a declination of -38° can never be viewed from Saskatoon. The following video shows the stars arcing across the southern horizon, as viewed from Sonoita, Arizona.

Learning Activity

Sonoita, AZ is located at a latitude of 32° N. At what altitude is the north celestial pole when viewed from Sonoita? At what declination are the stars at the south point on the horizon?

Click to Reveal Answer

Now let us return to the definition of a second coordinate, which is needed to specify locations of stars on the celestial sphere. Because the celestial sphere revolves around the Earth every twenty-four hours, astronomers find it useful to describe the celestial analogue of the Earth’s longitude, the right ascension, in units of hours, minutes, and seconds. Therefore, e.g., an observer’s celestial meridian advances by one second of right ascension every second.

As with the 0-point on the magnitude scale and the line of 0°-longitude on the Earth, the line of 0h 0m 0.0s-right ascension must be defined. By convention, astronomers specify this location as the line from north to south celestial pole that passes through the vernal equinox, the Sun’s position on the celestial sphere on the first day of spring in the northern hemisphere (and the first day of autumn in the southern hemisphere). In order to clarify where that point is, we’ll now turn to describing the Sun’s annual path through the celestial sphere.