In contrast to the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, the outermost planets Uranus and Neptune are smaller, denser, and contain far more heavy elements such as water, methane, and ammonia. These “ice giants” have very different internal structures and histories, yet outwardly appear as pale blue twins. Most of what we know about them comes from a single spacecraft: Voyager 2, which flew past Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989.

Uranus: the tilted planet

Uranus is unique in that its rotation axis is tilted by about 98°, so the planet essentially rolls around the Sun on its side. Each pole experiences 42 years of continuous sunlight followed by 42 years of darkness. The cause of this extreme tilt is still debated; the most likely explanation is that Uranus was struck by one or more large protoplanets early in its history.

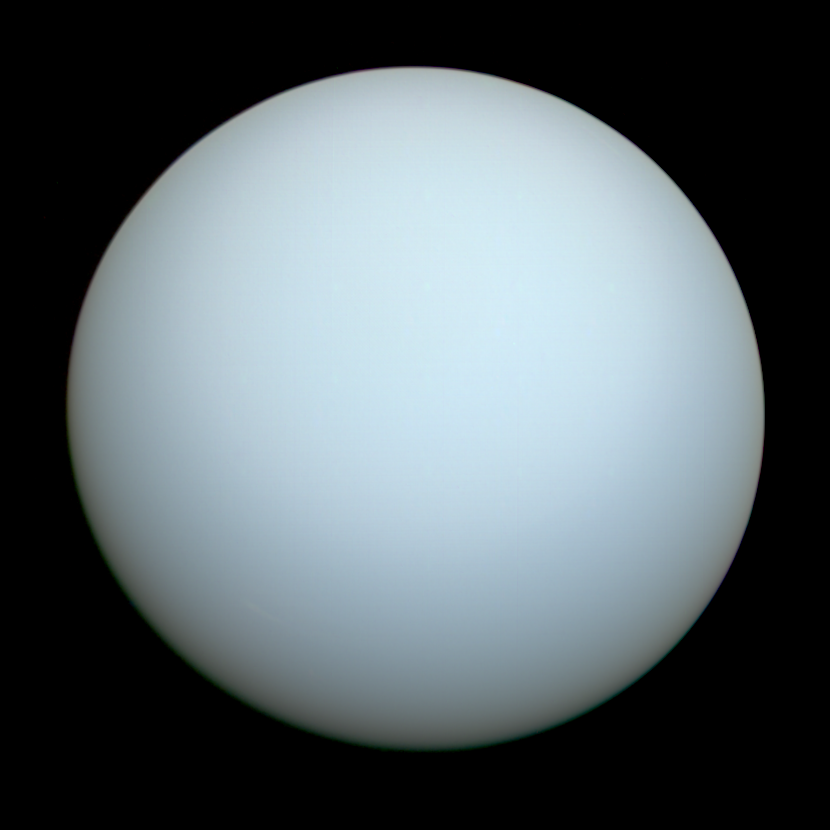

The planet’s bland blue-green color comes from methane in the upper atmosphere, which absorbs red light and reflects blue. Beneath the clouds, Voyager data suggest a deep layer of water–ammonia “slush” surrounding a rocky core. The magnetic field is also peculiar: it is both strongly tilted (59°) and offset from the planet’s center, implying a shallow, convecting dynamo rather than a deep metallic core.

Uranus’ moons and rings: Voyager discovered 10 new moons and confirmed a faint system of narrow rings first detected from Earth in 1977. The five major moons — Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon — show evidence of surprisingly complex geology. Miranda’s surface is patched with enormous cliff faces and canyons up to 20 km deep, suggesting partial melting and resurfacing. Ariel also shows signs of relatively recent tectonic activity.

Neptune: the active twin

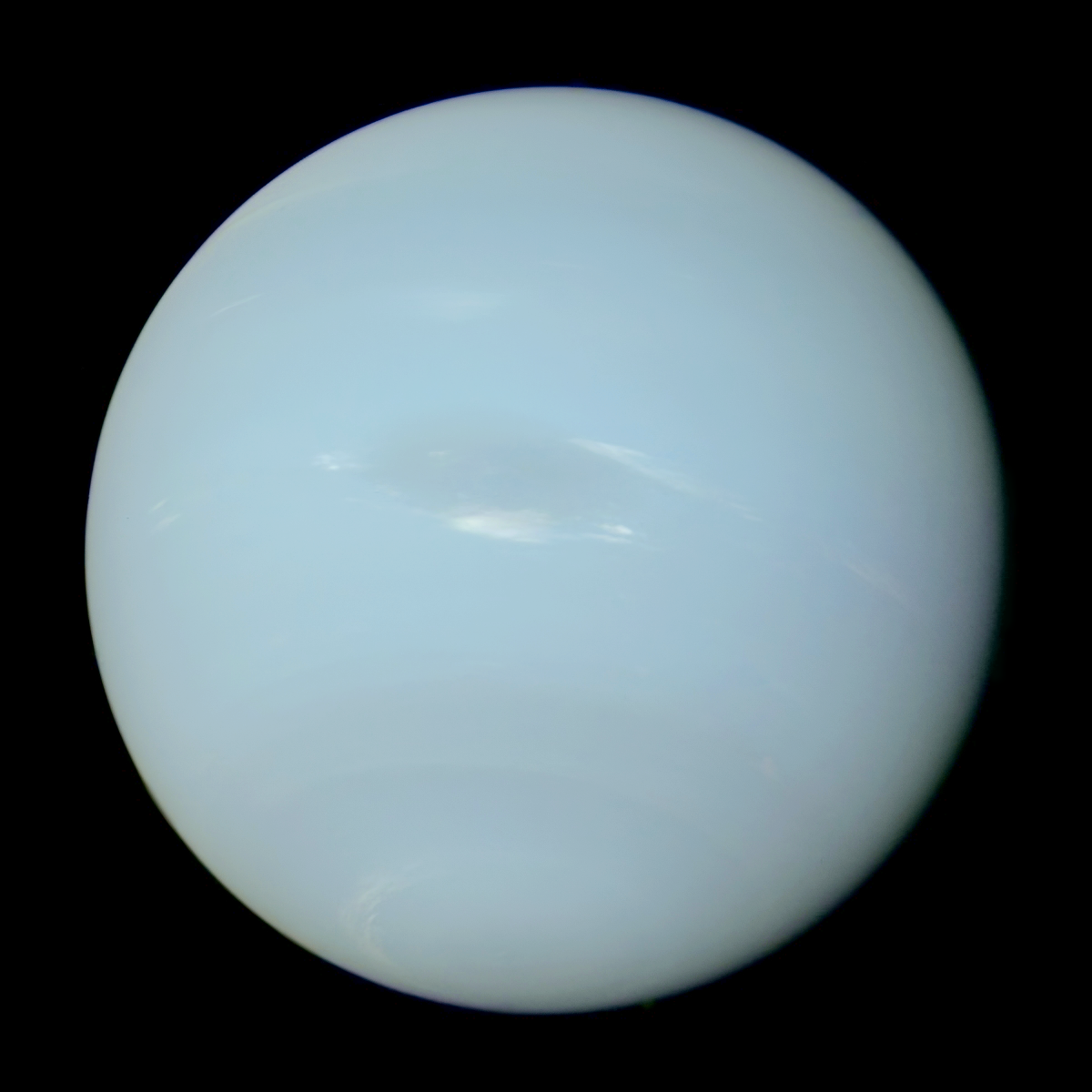

Neptune, slightly smaller but denser than Uranus, is the windiest planet in the Solar System, with jet streams reaching 2,000 km/h. Voyager revealed a strikingly dynamic atmosphere: bright white clouds of methane ice and a massive Great Dark Spot that rivaled Jupiter’s Great Red Spot. Later Hubble and JWST images show that these storm systems form and dissipate over just a few years.

Neptune’s deep blue color is due to slightly higher methane abundance and possibly an as-yet unidentified chromophore that enhances the blue hue. The planet radiates more than twice as much energy as it receives from the Sun, implying strong internal heat flow and active convection in its deep mantle of water, ammonia, and methane ices.

Rings and moons: Neptune’s faint rings contain clumps, arcs, and dust lanes shaped by the gravity of nearby small moons such as Galatea and Despina. Its largest moon, Triton, orbits backward (retrograde) and is likely a captured Kuiper-belt object. Triton has nitrogen geysers, a thin atmosphere, and a young, icy surface — making it one of the most intriguing worlds for future exploration.

Modern observations

Since the 1990s, telescopes such as Hubble and Keck have monitored Uranus and Neptune, revealing evolving weather and seasonal changes. Both planets show surprising variability for worlds so far from the Sun, suggesting that their deep interiors and tilted axes drive long-term atmospheric cycles.

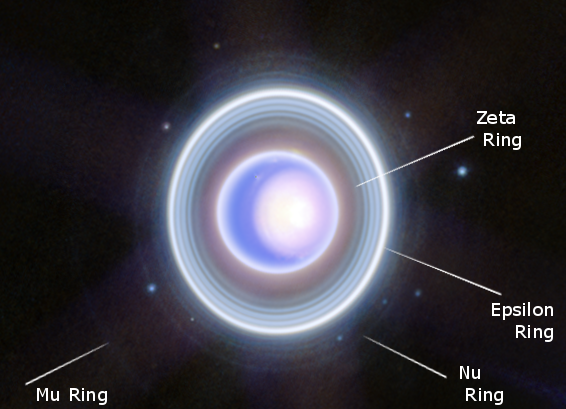

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has now provided the sharpest and most revealing views of these distant worlds ever obtained. In infrared light, Uranus appears with a bright polar cap, multiple narrow rings, and several small moons glinting against its disk. The planet’s changing polar features hint at a dynamic atmosphere that responds to its extreme seasons, each lasting more than 20 Earth years.

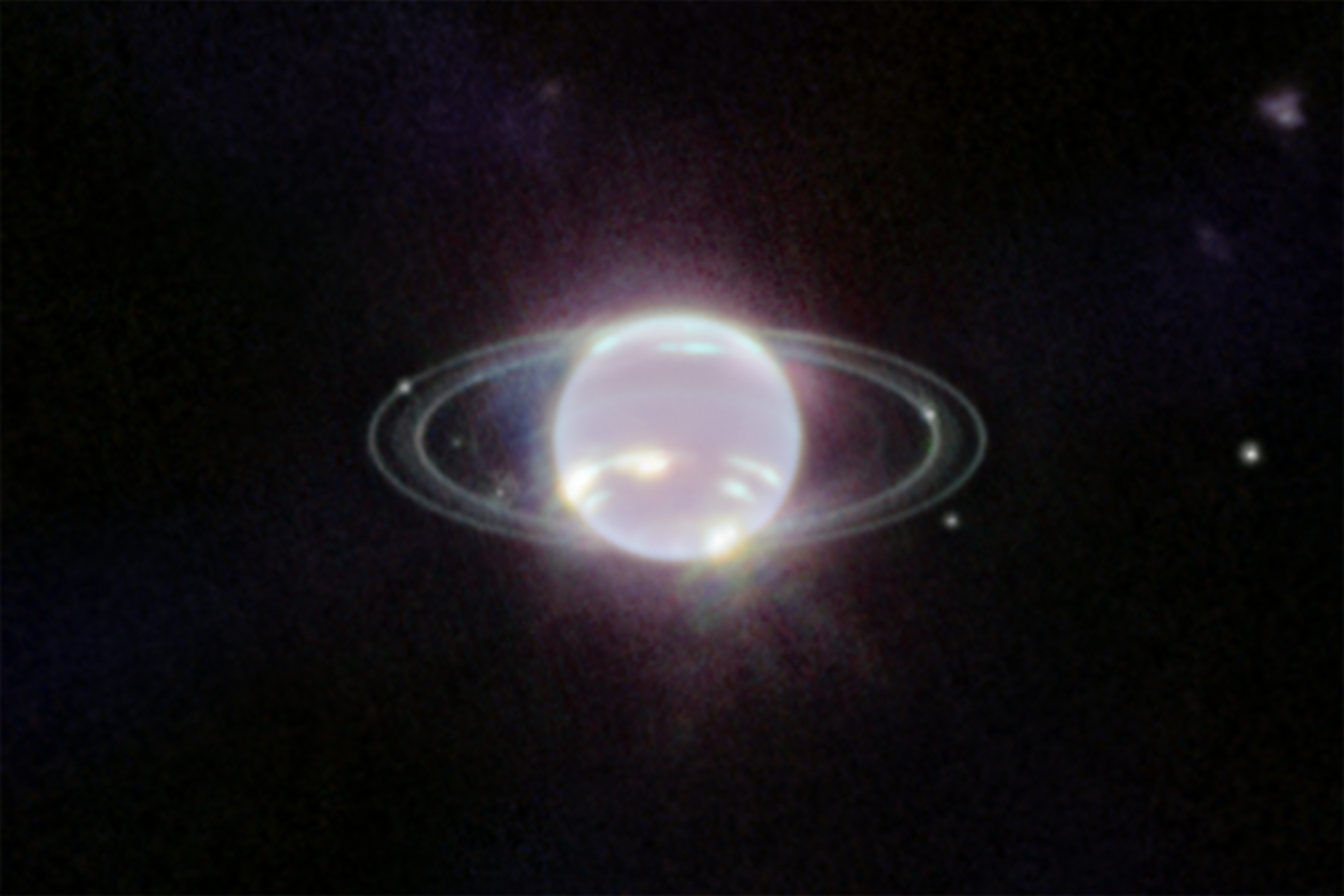

JWST’s observations of Neptune show a very different but equally active world. Its deep blue color comes from methane and possibly an additional, unknown absorber that enhances the contrast between bright methane-ice clouds and darker regions below. JWST detected Neptune’s entire ring system—visible for the first time in more than three decades—along with bright equatorial storms and subtle methane bands. The telescope also measured excess heat at Neptune’s south pole, suggesting that seasonal shifts redistribute energy through complex vertical mixing in its atmosphere.

Together, these observations demonstrate that even at the edge of the Solar System, weather never stops. Uranus’s changing polar cap and Neptune’s evolving storm systems show that both ice giants remain meteorologically active, powered by internal heat and rapid rotation as much as by the faint sunlight they receive.

Despite these advances, Uranus and Neptune are still the least explored of the major planets. No spacecraft has orbited either one, and nearly all of our direct data come from Voyager 2’s brief flybys in the 1980s. NASA and ESA are now developing concepts for an Ice-Giant Orbiter mission that could launch in the 2030s, providing the first sustained study of these cold, dynamic worlds.

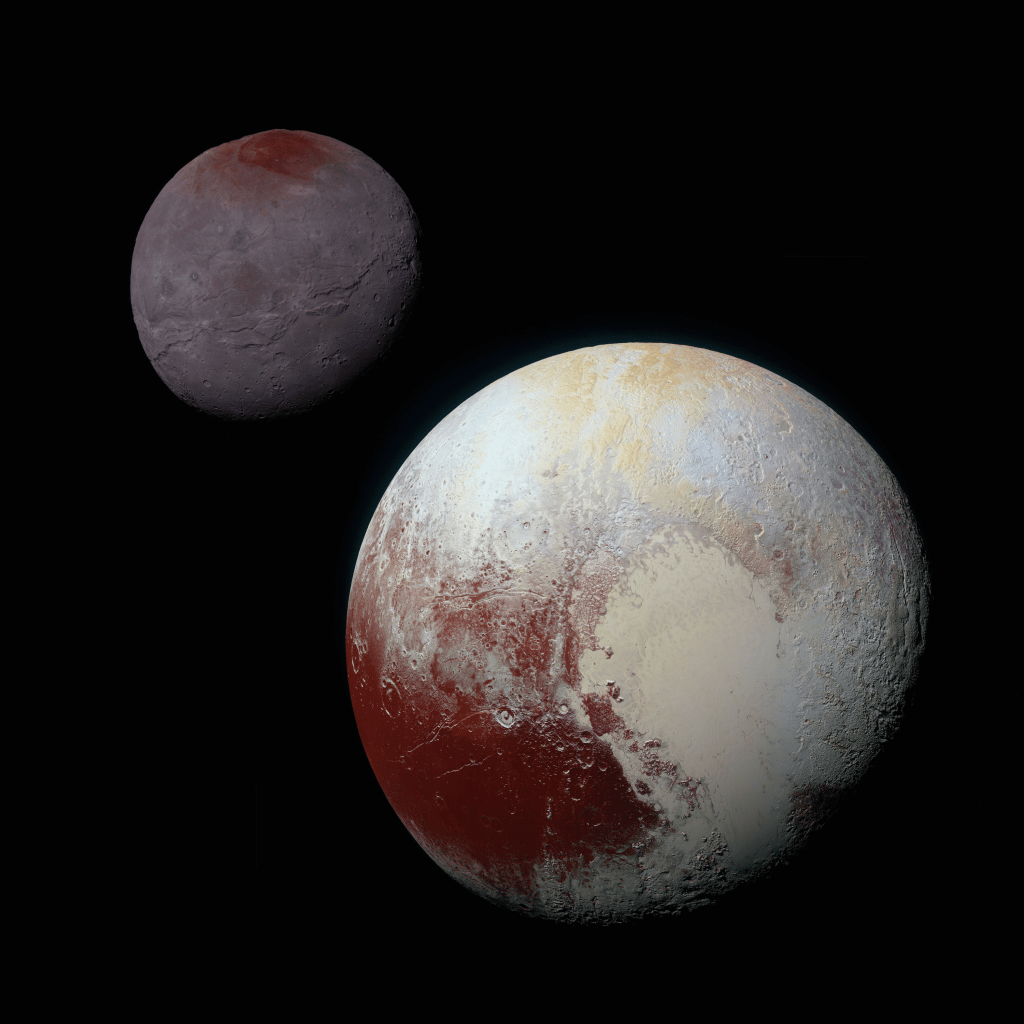

Pluto, Charon, and the New Horizons Revolution

For 85 years after Clyde Tombaugh found it in 1930, Pluto was just a fuzzy point of light — even in Hubble images. We knew its size only approximately, we could only map its surface albedo very crudely, and we didn’t know how active it was. That changed on 14 July 2015, when NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft flew past Pluto and its largest moon Charon at 14 km/s and sent back the first close-up images.

New Horizons confirmed something that the 2006 IAU decision had already implied: Pluto isn’t a failed “Planet X” — it’s the brightest, easiest-to-find member of the Kuiper belt. But the flyby also showed that even a small, cold, distant dwarf planet can be geologically alive.

What New Horizons found at Pluto

- A young, icy heart: The huge, bright, heart-shaped feature named Sputnik Planitia is a basin filled with nitrogen, carbon monoxide, and methane ices. It has almost no impact craters, which means the surface is being continually renewed.

- Convection in nitrogen ice: Slow overturning (“boiling”) of nitrogen ice from several km below the surface explains the cellular pattern seen in Sputnik Planitia — an unexpected kind of ice tectonics.

- An extended, hazy atmosphere: Pluto has a thin nitrogen atmosphere with layers of blue haze. Sunlight scattering through that haze is what made those famous “backlit” blue Pluto images.

- Complex coloration: Methane in Pluto’s atmosphere is broken apart by sunlight and reassembled into complex organics (tholins) that fall back and darken the surface.

- Varied terrains and possible cryovolcanism: Some regions look older and more cratered; others look young and possibly shaped by ice volcanism — eruptions of water or nitrogen ice instead of rock.

Put together, these results raised a big question for planetary science: how can a small, distant world keep enough internal heat to stay active billions of years after it formed? That’s one reason Pluto remains such a useful comparison point for other icy bodies like Triton, Enceladus, and Europa.

Charon and the small moons

New Horizons also flew through the Pluto–Charon binary, giving us our first good look at Pluto’s largest moon:

- Charon has a huge equatorial canyon system and a split between a smoother southern hemisphere and a rougher north, suggesting an early subsurface ocean that later froze and expanded, cracking the crust.

- Charon’s north pole is coated with a dark reddish cap (“Mordor Macula”), probably made of Pluto’s atmospheric gases that froze onto Charon and were chemically processed by sunlight.

- The tiny outer moons — Nix, Hydra, Kerberos, and Styx — turned out to be brighter and more irregular than expected, and some rotate chaotically.

Optional background: NASA’s pre-flyby documentary The Year of Pluto is still an excellent overview of how the mission was proposed, built, and navigated across the Solar System.

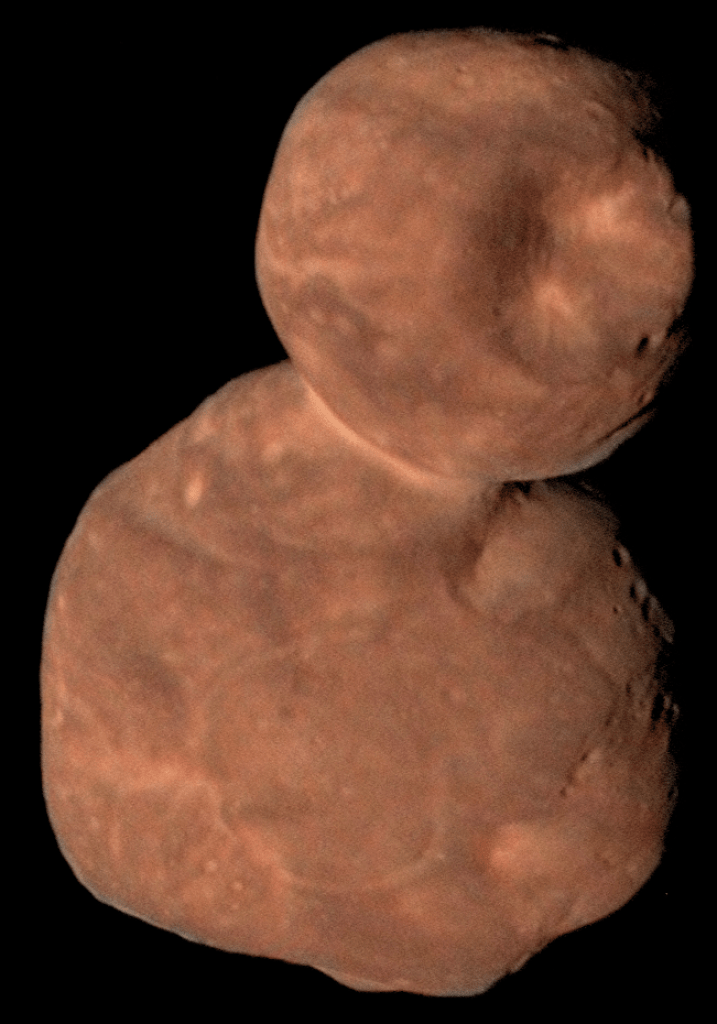

After Pluto: Arrokoth and the Kuiper Belt up close

New Horizons didn’t stop at Pluto. After the 2015 flyby, small course-correction maneuvers sent it toward a typical Kuiper-belt object, then known as 2014 MU69 and later named Arrokoth. On 1 January 2019 it flew past Arrokoth and showed it to be a gently merged, two-lobed body — basically two building blocks of a planet that never got accreted into a planet. That flyby gave us the first direct look at the kinds of primordial objects from which the outer Solar System formed.

Follow-up science and data

Because Pluto is so far away, New Horizons initially returned compressed “first look” images in July 2015 and then spent the following year downlinking the full-resolution dataset. By late 2016, the complete Pluto–Charon dataset was on the ground, and mission scientists began publishing detailed results on:

- “Blue” skies and layered hazes

- Evidence for ice volcanoes and different surface ages

- Convecting nitrogen ice in Sputnik Planitia

- Charon’s possible frozen ocean and crustal extension

- Methane “snowcaps” on mountain peaks

For a concise science summary, see The Pluto system: Initial results from its exploration by New Horizons:

Pluto’s surface displays diverse landforms, terrain ages, albedos, colors, and composition gradients. Evidence is found for a water-ice crust, geologically young surface units, surface ice convection, wind streaks, volatile transport, and glacial flow. Pluto’s atmosphere is highly extended, with trace hydrocarbons, a global haze layer, and a surface pressure near 10 microbars. Pluto’s diverse surface geology and long-term activity raise fundamental questions about how small planets remain active many billions of years after formation. Pluto’s large moon Charon displays tectonics and evidence for a heterogeneous crustal composition; its north pole displays puzzling dark terrain. Small satellites Hydra and Nix have higher albedos than expected.

Pluto, Charon, Arrokoth, Triton, and even the icy Uranian moons tell the same story: small, cold worlds can be active, layered, and geologically interesting. That’s exactly the kind of evidence we need for the next module, where we step back and ask: “Given everything we’ve now seen — rocky planets, gas giants, ice giants, dwarf planets, KBOs — how did the Solar System actually form to produce all of this?”