In contrast to the six planets you’ve explored so far, which were all “discovered” prehistorically, the discoveries of Uranus, Neptune, Pluto and the Kuiper belt all came long after the invention of the telescope. The discoveries of Uranus, Neptune and Pluto are all connected with one another, yet each story is unique, and each discovery ultimately resulted from the use of a different astronomical technique. You will now explore each of those discovery stories in turn.

Uranus

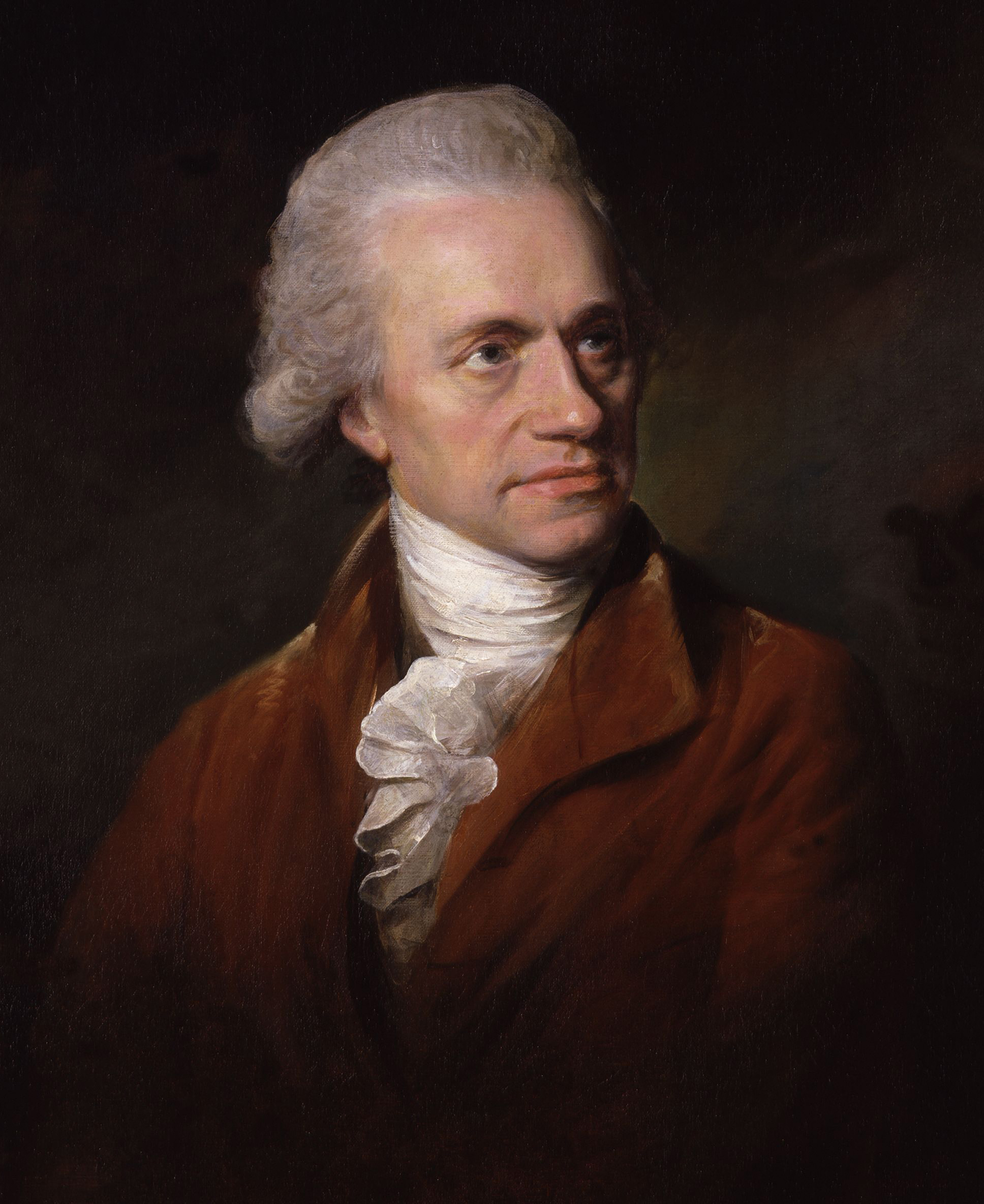

Uranus, the next planet out from the Sun after Saturn, was discovered by William Herschel on 13 March 1781, as he attempted to systematically map the sky.

Uranus is:

- twice as far from the Sun as Saturn (19 AU vs 9.5 AU semi-major axis),

- its radius is less than half of Saturn’s (25,362 km vs 58,232 km; hence, the area of the apparent disk we see is less than 1/4 the area of the Saturnian disk), and

- its albedo is lower than Saturn’s (0.300 vs 0.342).

Each of these three things leads to Uranus appearing dimmer to us, so it should be no surprise that Uranus is a lot dimmer than Saturn. In fact, Uranus is nearly 6 magnitudes, or 1000 times, dimmer than Saturn.

A thing you may find surprising, however, is that Uranus is actually faintly visible to the naked eye under dark sky conditions. For this reason, it was actually observed multiple times by star cataloguers prior to its discovery. Probably the main reason why astronomers prior to Herschel had failed to recognise Uranus as a planet is its 84-year orbit. As it takes 84 years for Uranus to go once around the ecliptic, its motion relative to the background stars is difficult to notice on consecutive observations, and therefore went unnoticed by cataloguers.

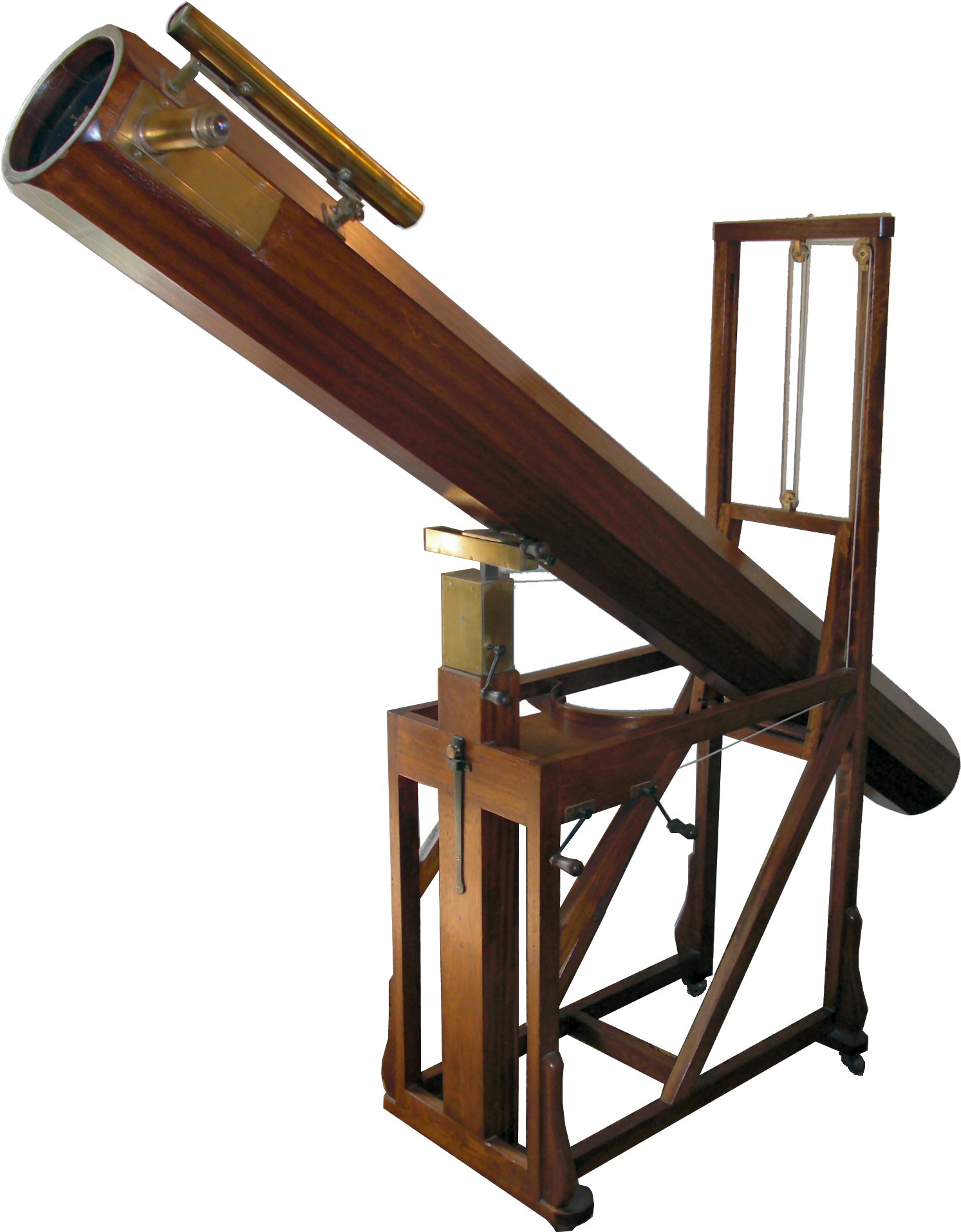

William Herschel used to discover Uranus. Source.

When Herschel first observed the planet through a 6-inch reflector he had constructed himself (see Figure 9-2), he noted that it appeared slightly larger than the surrounding stars and suggested that it might be a comet. However, by examining the old records in which Uranus had been observed but mistaken for a star, other astronomers were soon able to calculate its orbit and determined that it must be a planet located beyond Saturn’s orbit.

At the time of the discovery, Herschel was working as a schoolteacher, practising amateur astronomy in his spare time. The discovery of a new planet made him instantly famous, and, after naming it Georgium Sidus (George’s Star) after King George III, he secured an annual stipend of £200, which enabled him to work full-time as a professional astronomer. As you’ll recall from the Module 6 introduction video, Herschel went on to make a number of important discoveries, including Saturn’s moons Enceladus and Mimas, Uranus’ two largest moons Titania and Oberon, the discovery of seasonal variation in Mars’ polar ice caps, and the discovery of infrared radiation. And when the Royal Astronomical Society was founded in 1820, Herschel was its first president.

Herschel’s name for the new planet, however, did not stick. In countries such as France and the United States, for instance, where the name of the British King was not popular, the planet was referred to as Herschel until the name Uranus was universally adopted.

Neptune

The story of Neptune’s discovery is actually linked with Uranus, but it took place very differently. The planet is another 11 AU more distant from the Sun than Uranus, has a slightly lower albedo (0.290), and, with a mean radius of 24,622 km, it’s also slightly smaller. With an apparent magnitude of 8, Neptune is decidedly not visible to the unaided eye.

Neptune’s discovery is one of the most well-known in the history of science, both because it was a great confirmation of Newtonian mechanics and because of the controversy that ensued over the priority of the discovery. Watch the video as physics educator Paul Hewitt describes the discovery of Neptune.

The discovery of Neptune was one of the greatest achievements of Newtonian mechanics. It elevated the theory from one that could be used to describe everything that was already known about planetary motion, to one that could be trusted, in the face of an observational inconsistency, to predict the existence of something as substantial as another planet in our Solar System.

You may recall from Module 3 that physicists did not wholeheartedly accept Newton’s law of universal gravitation. It posited the existence of a universal force that acts instantaneously at arbitrarily large distances between two masses. Newton refused to speculate about where this force came from, famously claiming “hypotheses non fingo” (I feign no hypotheses). Because of the uncertainty in the theory, many astronomers justifiably felt that the discrepancy between calculations of Uranus’ orbit and its observation was due to the law breaking down. Perhaps Newton’s action-at-a-distance really only extended so far, etc.

Two nineteenth century mathematicians, however, trusting in Newtonian mechanics, crunched the numbers to figure out where an additional planet would need to be located if it could be assumed that Newton’s law was actually right. There has been a great amount of controversy over just about every aspect of the discovery. A good place to start reading about this controversy is with the Wikipedia page Discovery of Neptune and its sources. Here, we’ll stick with just a few of the most relevant facts.

In England, in 1845 John Couch Adams (Figure 9-3) worked on calculating the possible position of the new planet based on observations of Uranus’ position. He communicated his results to the director of the Cambridge Observatory, James Challis, but no search was initiated for the planet at that time.

In the same year, unaware of Adams’ work on the same problem, the French mathematician Urbain Le Verrier (Figure 9-4) began his own calculations. Word of Le Verrier’s calculations renewed British interest in the problem, and Challis began searching for the planet during the summer of 1846, while Adams continued his mathematical work on the problem.

In the meantime, Le Verrier completed his calculations in the autumn of 1846, unaware of the mad scramble taking place in England. Unable to attract the interest of any French astronomers, he eventually sent his results to Johann Gottfried Galle at the Berlin Observatory. Galle (Figure 9-5) received the letter on 23 September 1846, and just after midnight, after less than an hour of searching, found Neptune within 1° of Le Verrier’s prediction by comparing with a recently drawn star chart. He observed Neptune’s slight motion over the course of another two nights before replying to Le Verrier that the planet really exists.

The discovery of Neptune was a great triumph for Newtonian mechanics, but a sore loss for the British astronomers. It turned out that Challis had actually observed Neptune on August 8 and August 12, but failed to recognise it because his star map was outdated.

Pluto and the Kuiper Belt

After the discovery of Neptune, there was considerably more speculation about the possible existence of a ninth planet. And, in fact, further observations of Uranus and Neptune indicated that there was still some unexplained irregularity, particularly in Uranus’ orbit, which seemed not to be fully accounted for by the presence of Neptune.

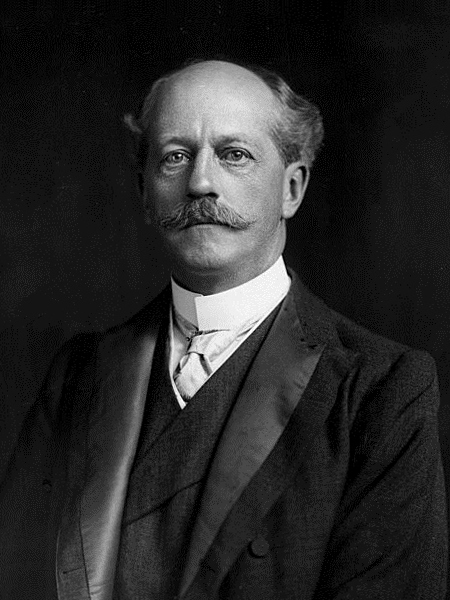

The problem gained notoriety, and in 1894 Percival Lowell (Figure 9-6) founded the Lowell Observatory with its 24-inch refractor, eventually launching an extensive campaign to search for a trans-Neptunian object (TNO) which he called Planet X. (Lowell was also one of the main figures in the history of Martian canal mapping, which you learned about in Module 7).

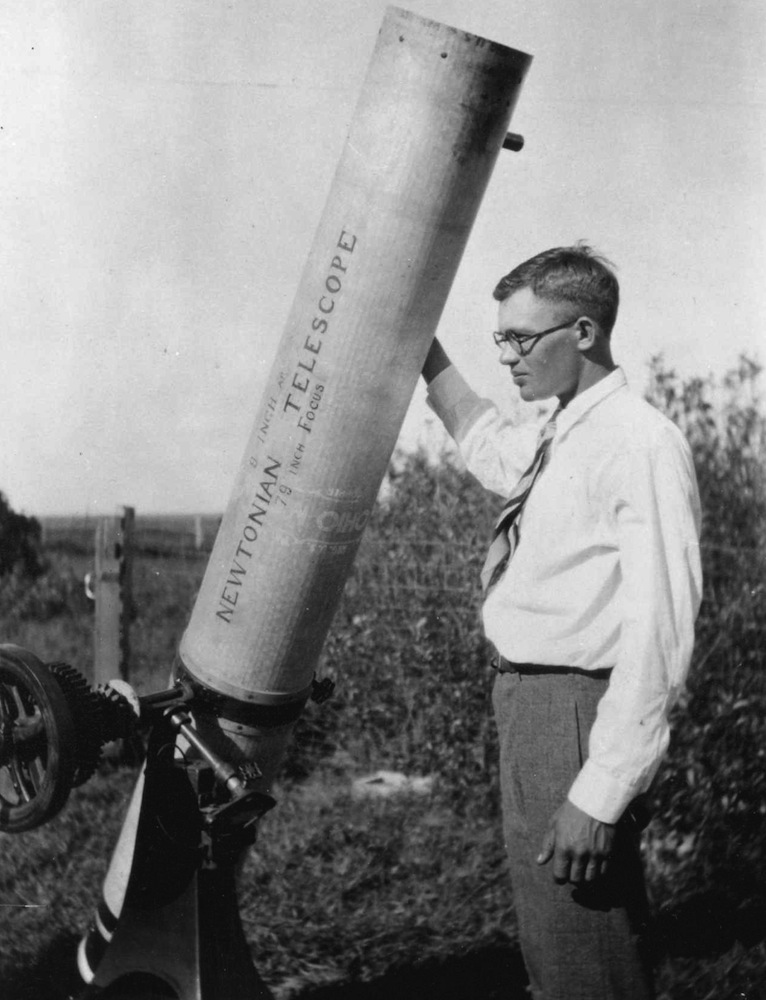

parents’ Kansas farm with his homemade 9-inch telescope sometime prior to his 1930 discovery of Pluto. Source.

Lowell died in 1916, having failed to find Planet X. A long legal dispute delayed the search for more than a decade. Then, in 1929, a Kansas farmboy named Clyde Tombaugh, who had impressed the observatory’s director with astronomical drawings made using his homemade telescope (see Figure 9-7), was hired to resume the search for a slow-moving, distant object.

Tombaugh photographed the ecliptic two weeks apart, then used a blink comparator to flip between the two plates and see which “star” had moved. On 18 February 1930 he spotted a faint, slow-moving object only about 6° from Lowell’s predicted position: Pluto had been found.

There was only one problem: Pluto was far too dim. To be massive enough to explain Uranus’ orbit (Lowell’s estimate was ~6.6 Earth masses) it would have needed to be both huge and dark. Later observations — especially after Pluto’s moon Charon was discovered in 1978, letting astronomers measure Pluto’s mass using Kepler’s 3rd law — showed Pluto is only about 1/500 Earth’s mass. That is nowhere near enough to perturb Uranus’ orbit.

The “missing mass” puzzle was finally resolved, very quietly, after Voyager 2 flew past Neptune in 1989. Voyager refined Neptune’s mass downward by about 0.5%. With the improved mass, the irregularities in Uranus’ orbit basically disappeared. In other words, Pluto’s discovery in 1930 was a real discovery — but it was also a fluke.

From one oddball to a whole population (1992 →)

For decades, Pluto looked like a lonely misfit — small, on an eccentric and inclined orbit, different from everything else. That picture changed in 1992, when astronomers discovered 1992 QB1, a small body beyond Neptune that was clearly not Pluto and not a comet. That single discovery triggered wide-field CCD surveys of the outer Solar System, and suddenly it became clear: Pluto is just the brightest member of a large population of icy bodies between about 30 and 50 AU. This region is the Kuiper belt, named (a bit loosely) after Gerard Kuiper.

Once astronomers realised there were hundreds and then thousands of these objects, Pluto stopped looking like “planet #9” and started looking like “the first Kuiper-belt object to be found, in 1930, by accident.”

Kuiper-belt dynamical families

Objects in the 30–50 AU region fall into a few main groups, depending on how they interact with Neptune:

- Plutinos: objects in a 2:3 resonance with Neptune — they go around the Sun twice for every three Neptune years. Pluto itself is the best-known plutino.

- Twotinos: objects in a 1:2 resonance — they orbit once for every two Neptune years.

- Classical Kuiper-belt objects (also called cubewanos): objects on more circular, non-resonant orbits farther out; 1992 QB1 was the prototype.

Resonance is the key idea here: even though some of these orbits cross Neptune’s orbit, the timing of the resonance means they never get close enough to Neptune to be scattered away.

Beyond the belt: the scattered disc

Farther out is the scattered disc. These objects often did have close encounters with Neptune in the past and were literally flung onto elongated orbits that can reach 100 AU or more. Eris — discovered in 2005 and slightly more massive than Pluto — is one of these scattered-disc objects.

Comparing Eris with a true planet like Neptune makes the classification problem obvious. Eris is:

- small (17th most massive body in the Solar System);

- on a very stretched orbit (perihelion ~38 AU, aphelion ~98 AU);

- clearly related to the Kuiper-belt / scattered-disc population.

Pluto is even less massive, and the only reason it wasn’t also scattered is that it’s locked in resonance with Neptune.

Why Pluto became a dwarf planet (IAU 2006)

By the mid-2000s, surveys (including those led by Mike Brown) had turned up objects as big as or even slightly bigger than Pluto. Astronomers had two choices:

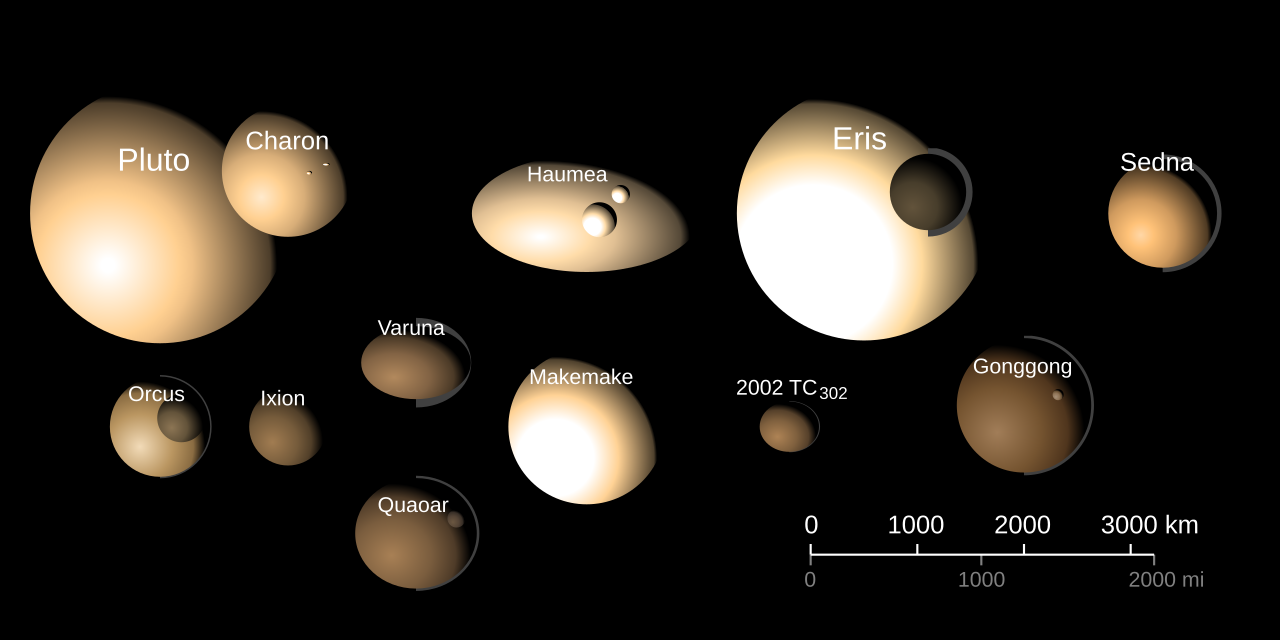

- either call Pluto, Eris, Haumea, Makemake, and every future Pluto-sized TNO a planet,

- or admit that Pluto is just the brightest member of a large, outer population and create a new category.

In 2006 the IAU chose the second option. Pluto, Eris, Haumea, Makemake, and (in the inner Solar System) Ceres were put in a new class called dwarf planets. The logic was: Pluto wasn’t demoted because it was “bad at being a planet”; it was reclassified because we finally realised it belongs to a crowd of similar bodies.

Learning Activity

In 2006, following a flurry of discoveries since 1992 of more than 1000 TNOs, the IAU General Assembly passed two resolutions: the definition of a “planet”, and the definition of Pluto-class objects, known as “dwarf planets”. The first three of the new class of dwarf planets were Ceres (an asteroid you’ll study in the next module), Pluto and Eris.

Explore the following link to the IAU 2006 General Assembly press release to learn which criteria were chosen to separate “planets” from “dwarf planets,” and compare that with what you have just read.

Since 2006, the IAU has officially named two more dwarf planets, Haumea and Makemake, although the number of probable dwarf-planet candidates already discovered is on the order of 100 (see Figure 9-9). Apart from Ceres, which is the only asteroid massive enough to be round, the rest are trans-Neptunian dwarf planets, also called plutoids.

Exploration continues

Our exploration of the Solar System is still far from over. We know where its boundary begins because in 2012, at about 121 AU, Voyager 1 finally crossed into interstellar space, as the video below explains.

Even so, Voyager 1 is still well inside the vast, hypothetical population of icy bodies called the Oort Cloud, which may extend out to tens or even hundreds of thousands of AU. You will learn more about that in the next module.

Meanwhile, spacecraft are still giving us close-ups of Kuiper-belt worlds. In July 2015, NASA’s New Horizons mission flew past Pluto and Charon, revealing a surprisingly active surface. In January 2019 it flew past the Kuiper-belt object Arrokoth (2014 MU69), the first close view of a “typical” KBO.

And since 2016, astronomers have been debating a possible very distant, very massive “Planet Nine”, proposed by Mike Brown and Konstantin Batygin to explain a clustering of some extreme TNO orbits. As of 2025, no such planet has actually been observed, so it remains an open question.

On the next page, you’ll leave the discovery stories behind and look at what Uranus and Neptune are actually like — their tilted rotation, their ring systems, their main moons, and the modern Hubble/Keck/JWST observations that are filling in what Voyager 2 couldn’t see in one quick flyby.