The word terrestrial originates from the Latin terra, meaning “Earth.” It literally means “Earth-like.” Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars—our terrestrial planets—are solid, rocky worlds with dense iron–nickel cores and silicate mantles. Their mean densities range from about 3.9 to 5.5 g/cm3 (for Mars and Earth, respectively). Each has a clearly defined solid surface and a relatively thin atmosphere compared to its diameter.

The word Jovian derives from Jove, another name for Jupiter, and literally means “Jupiter-like.” Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—all somewhat similar to Jupiter in size and composition—are therefore called Jovian planets (see Figure 8-1). These are the giants of our Solar System, each with broad, turbulent atmospheres, rapid differential rotation (their equators rotate faster than their poles), and deep interiors where gases are compressed into exotic states of matter.

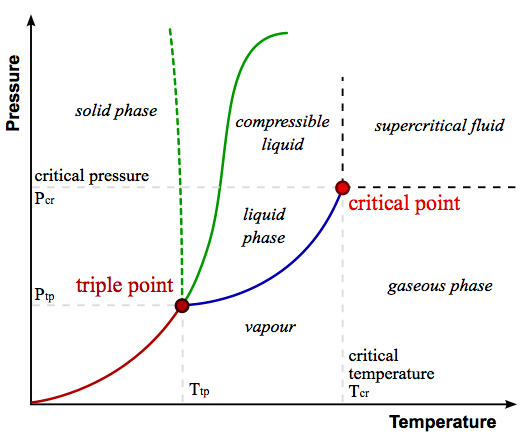

The Jovian planets are also known collectively as the giant planets, and are often divided into two informal groups: the gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn) and the ice giants (Uranus and Neptune). However, these labels can be misleading. In reality, all four planets consist mainly of supercritical fluids—neither purely liquid nor gaseous—formed by extreme pressures and temperatures deep within their interiors (Figure 8-2). For consistency, and to emphasize their shared physical structure, we use the term Jovian planets throughout this module.

With masses ranging from 14.5 to 318 Earth masses (for Uranus and Jupiter, respectively) and volumes between 58 and 1321 times that of Earth (for Neptune and Jupiter), all the Jovian planets are vastly larger and more massive—but much less dense—than the terrestrial planets. Neptune is the densest of the four (1.64 g/cm3), while Saturn, with its huge volume but relatively low mass, is the least dense of all (0.69 g/cm3)—so low that it would float in water if such an ocean could contain it.

The Jovian planets are rich in molecular hydrogen (H2) and helium, which together make up nearly 100 percent of their composition by volume. At pressures exceeding about 1.4 million bar, the hydrogen in Jupiter and Saturn transitions into metallic hydrogen—a fluid that conducts electricity and generates each planet’s powerful magnetic field through the dynamo effect. These magnetic fields are vastly stronger and more extensive than Earth’s, stretching millions of kilometres into space and shaping enormous magnetospheres.