The interaction between Phoebe and Iapetus, discussed in the previous section, highlights one of the biggest differences between the Jovian and terrestrial planets: their moons. Whereas the four terrestrial planets host only three small, geologically inactive moons—the Moon, Phobos, and Deimos—the Jovian planets possess dozens. Many of these moons are large, active worlds in their own right, formed from the same swirling disks of gas and dust that surrounded Jupiter and Saturn early in the Solar System’s history.

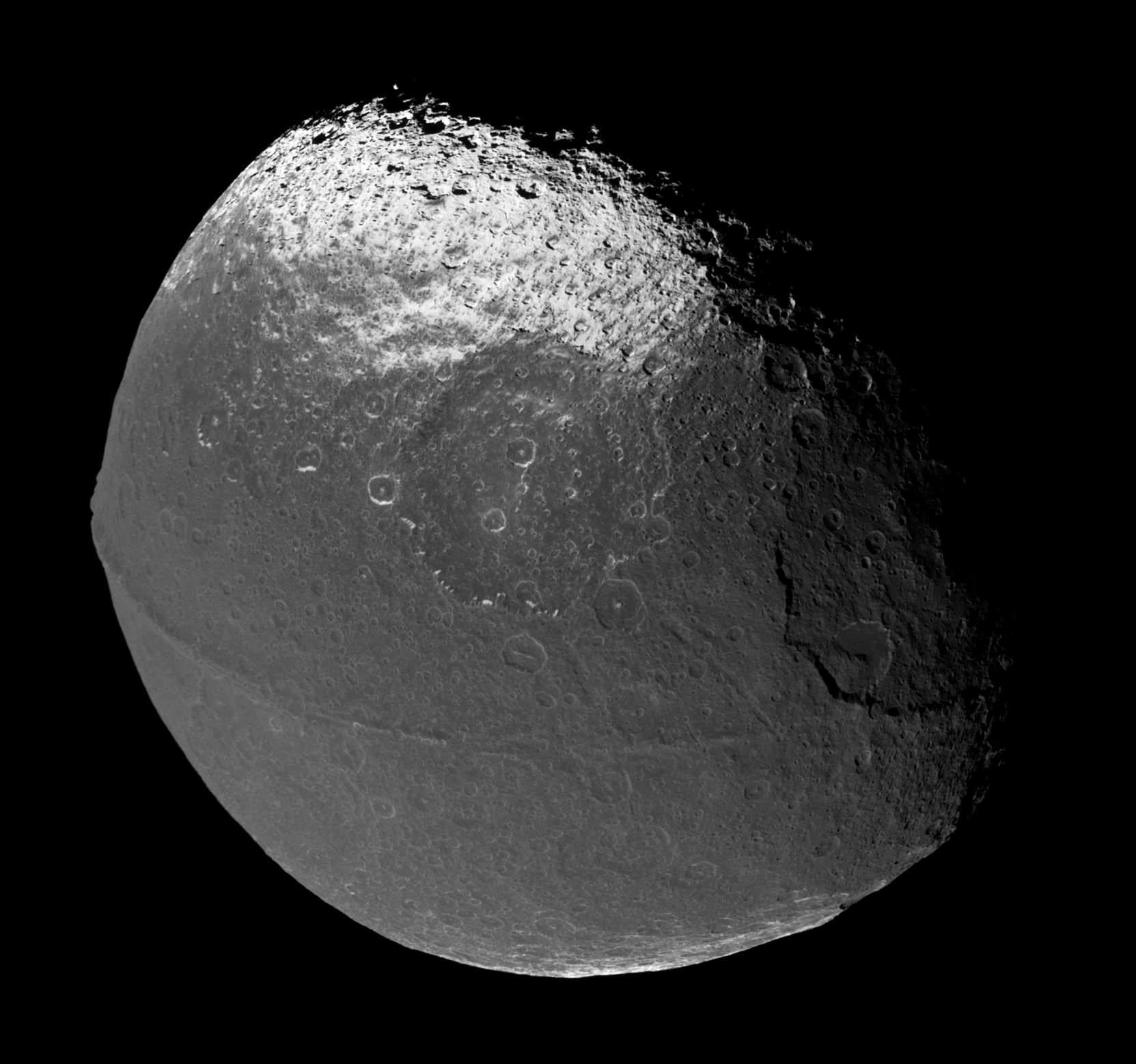

The mosaic image of Iapetus shown in Figure 8-5 reveals a striking feature: a ridge up to 20 km high running along its equator, giving the moon a walnut-like shape. The ridge’s origin is still not well understood. It may be the remnant of an early ring system that collapsed onto the surface or the result of internal convection. Regardless of the cause, this feature illustrates how the Jovian moons exhibit geological diversity far beyond anything seen among the smaller, inert moons of the terrestrial planets.

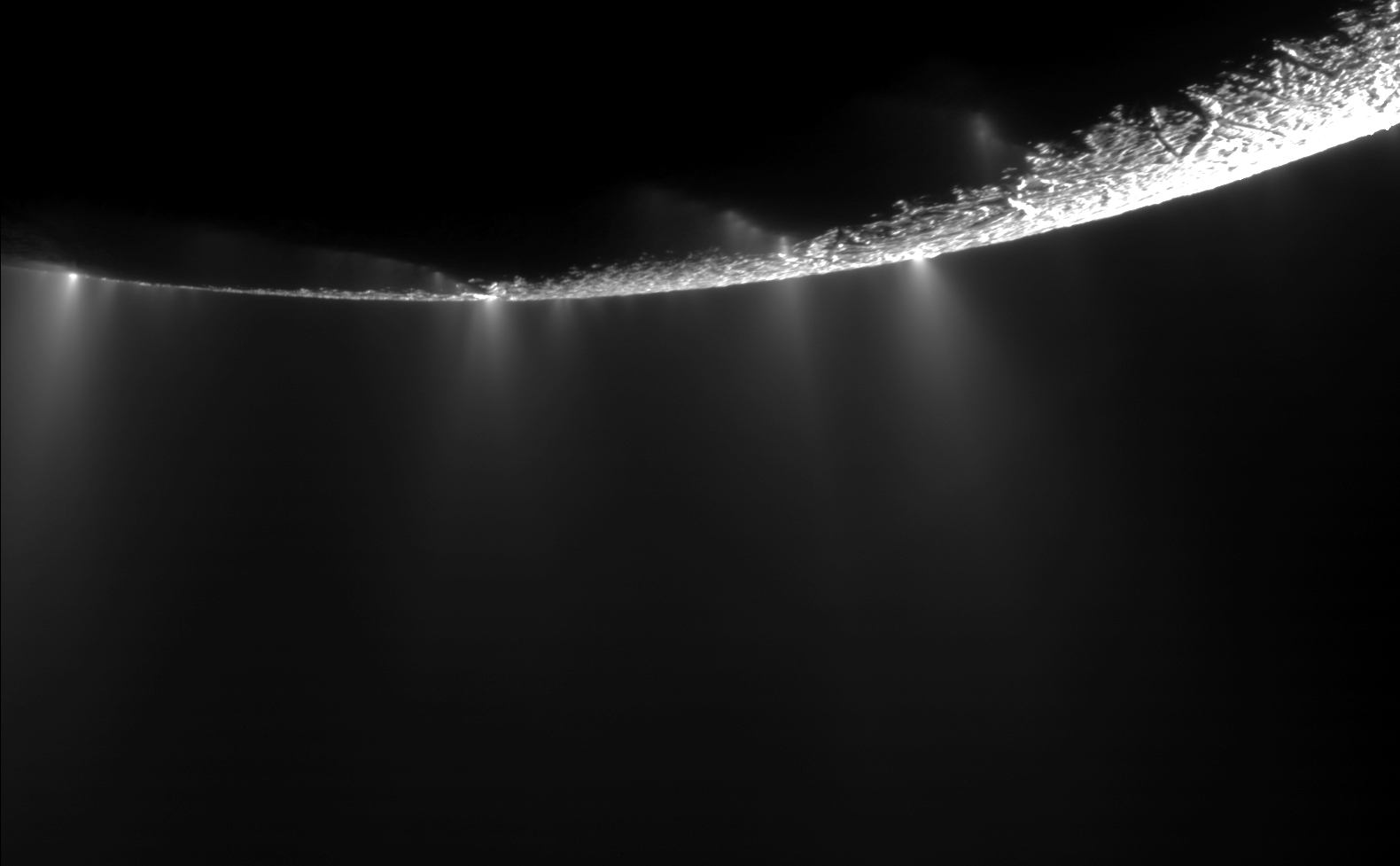

Another Saturnian moon, Enceladus, provides an even more dramatic example of geological activity. Observations from the Voyager missions first hinted that Enceladus might be the source of Saturn’s E ring, since its location matched the densest part of the ring and its southern hemisphere appeared unusually smooth. The likely explanation was tidal heating—the continual flexing of the moon by Saturn’s gravity and by resonances with other moons, which generates internal heat.

In 2005, shortly after its arrival at Saturn, the Cassini spacecraft captured remarkable images of geysers blasting from long cracks at Enceladus’s south pole—nicknamed “tiger stripes” because of their appearance (see Figure 8-6). These plumes, composed mostly of water vapour and ice grains, confirmed that active geology was reshaping the moon’s surface in real time.

The first video below provides a narrated overview of how Cassini’s flybys revealed Enceladus’s plumes and surface fractures, showing how tidal flexing produces enough internal energy to sustain a subsurface ocean.

In 2015, after studying subtle wobbles in Enceladus’s rotation, scientists concluded that its icy crust must be floating atop a global ocean. Later that year, Cassini flew through one of the south-polar geysers at a height of only 49 km to directly sample the plume material. The following video explains what the spacecraft detected during those flybys and why the results—especially the detection of molecular hydrogen—suggest that Enceladus’s ocean may have hydrothermal activity at its rocky seafloor, providing all the ingredients necessary for microbial life.

While Enceladus’s discovery revolutionised our understanding of subsurface oceans, Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, revealed something equally extraordinary: a thick, nitrogen-rich atmosphere and surface liquids composed of methane and ethane. The Cassini–Huygens mission carried a small probe, Huygens, designed to descend through Titan’s hazy atmosphere. On 14 January 2005, it became the first spacecraft to land on a world in the outer Solar System, transmitting data for 72 minutes before losing contact with Cassini.

The first video below reconstructs Huygens’s two-and-a-half-hour descent through Titan’s clouds and its landing on a solid surface of frozen methane and water ice.

To commemorate the tenth anniversary of the landing, ESA compiled the probe’s major discoveries, including Titan’s dense atmosphere, river channels, and hints of subsurface liquid water. Later radar scans from Cassini revealed vast methane–ethane lakes and seas near Titan’s poles, confirming that Titan is the only body beyond Earth with stable surface liquids. The next video presents these findings through false-colour maps that highlight Titan’s hydrocarbon lakes and dunes.

Although Titan’s surface liquids are not water, its atmosphere and organic chemistry make it a valuable analog for early Earth. Meanwhile, Enceladus showed that a world doesn’t even need an atmosphere to host liquid water—only internal heat and a subsurface ocean. Similar processes occur among Jupiter’s large Galilean moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Of these, Europa and Ganymede are believed to have global oceans beneath their icy crusts. Ganymede’s ocean may be buried between thick ice layers, but Europa’s is thought to be in direct contact with its rocky mantle, providing chemical energy that could sustain life. NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper mission—scheduled for launch in 2025—will perform detailed surveys of Europa’s surface and environment to investigate this possibility.

The following video introduces the Europa Clipper mission, outlining its objectives, instruments, and the scientific motivation for exploring Europa’s potentially habitable ocean world.

Finally, Jupiter’s moon Io demonstrates the extreme end of tidal heating. The innermost of the Galilean moons, Io is the most volcanically active body in the Solar System, with over 400 active volcanoes constantly resurfacing the planet. The image in Figure 8-7—taken by Voyager 1 in 1979—shows two large volcanic plumes erupting hundreds of kilometres above the surface. Io’s intense internal heating arises from its eccentric orbit and gravitational interactions with Europa and Ganymede, which keep its interior in perpetual motion.

Io’s volcanism interacts strongly with Jupiter’s immense magnetic field, producing streams of charged particles that flow along magnetic field lines and generate brilliant auroras at Jupiter’s poles—thousands of times more energetic than those seen on Earth.

Together, these moons demonstrate that the Jovian systems are extraordinarily diverse: icy oceans under kilometers of ice, methane lakes beneath orange skies, and worlds of lava and lightning. Each is a miniature planet, shaped by the same fundamental forces—gravity, magnetism, and heat—that sculpted the Solar System itself. By studying them, we gain new insight into how planets evolve and where life might emerge beyond Earth.