The answer to the question of why there is no liquid water on Venus is actually a relatively simple one to give. Venus lies just inside the inner edge of the Sun’s habitable zone—close enough that solar heating and greenhouse feedback make its surface too hot for liquid water.

Accurate modelling of a planet’s surface temperature requires accounting for a number of complexities such as the albedo of different surface and atmospheric components, which all depend on wavelength (think of what you learned in Module 5 about colour!), as well as the planet’s greenhouse effect and the geometry of incident radiation from the Sun. However, we can start developing a pretty decent estimate of any planet’s temperature by modelling it as a blackbody, using the average albedo of its atmosphere.

The first step is accounting for the amount of radiation received and dividing that over the surface of the entire planet. Let us begin with the Earth. In Module 5, you learned that the solar constant—the amount of radiation per unit area from the Sun that is incident above Earth’s atmosphere—is 1361 W/m2 on average. From the Sun’s perspective, the Earth looks like a two-dimensional disk with radius RE, the Earth’s actual radius. The total area of a disk this size is πRE2. This is the total area of the Earth that intercepts sunlight. Multiplying this value by the solar constant gives the total power that the Earth receives from the Sun—roughly 1017 W.

Now, in order to determine the average amount of radiation per unit area that the Earth’s surface receives, we simply divide by the surface area of the Earth—i.e. divide by 4πRE2, the area of a sphere of radius RE. Since the area of the two-dimensional disk that the Sun sees is one-quarter the area of the surface of the Earth, this effectively means dividing the solar constant by 4.

If all the light received by the Sun were to reach the surface of the Earth, and if the Earth were a perfect blackbody, we could therefore calculate its temperature by applying the Stefan-Boltzmann law from Module 5,

with L/A = 340 W/m2 and σ = 5.670 x 10–8 W/(m2⋅K4). And in fact, it turns out that the blackbody assumption is not so bad as long as we account for the Earth’s average albedo. This accounts for the electromagnetic radiation that the Earth reflects back into space, while the rest should theoretically go into warming it up and be released as blackbody radiation.

While it may seem surprising at first, the Earth actually does a pretty good job of absorbing sunlight. Its albedo is only 0.29, on average, which means it absorbs about 70% of incident sunlight. This is partly because our atmosphere is mostly transparent to visible light, where the Sun emits the majority of its radiation.

We have already determined that if 100% of the radiation received from the Sun were to reach Earth’s surface, the average energy available per unit area would be 340 W/m2, i.e. one-quarter the solar constant. 70% of this value is 240 W/m2, which is actually all that gets through, on average. And this value can finally be used, along with the Stefan-Boltzmann law, to estimate the average surface temperature of the Earth:

T = [240 W/m2 / 5.670 × 10-8 W/(m2⋅K4)]1/4 = 255 K = -18 °C.

It turns out that the Earth’s blackbody temperature is below the freezing point of water! So, why is most of the water on the surface of the Earth liquid? The answer, as you’ll recall from the Crash Course Astronomy video on the Earth, is the greenhouse effect—i.e. the fact that the water vapour in our atmosphere is largely transparent to visible light, but opaque to infrared. Therefore, visible light gets in through our watery atmosphere, which heats the Earth and is subsequently re-emitted roughly as a blackbody spectrum, and then that blackbody radiation can’t get through the atmosphere, but instead bounces around, heating both the air and the ground. The Earth’s average temperature is roughly 15 °C as a result of this greenhouse effect, which is why liquid water can and does exist on its surface.

Now, the question we have been attempting to address in this section is why liquid water is not able to exist on the surface of Venus. As noted at the beginning of the section, this is because Venus orbits too near to the Sun, and therefore receives too much radiation. Specifically, since Venus orbits the Sun at a distance of roughly 0.72 AU, its “solar constant” is 2610 W/m2. The same calculations we’ve just performed therefore indicate that if Venus had the same atmospheric composition and albedo as Earth (≈ 0.29), its equilibrium temperature would be about 299 K (26 °C) even before including any greenhouse effect.

While 26 °C is a very nice temperature, there are a few problems with this average temperature that must be considered. First of all, it is an average temperature, calculated over the poles, the night time side of the planet, and the daytime side. The temperature directly under the Sun would have to be much hotter. Second of all, we haven’t accounted for Venus’ greenhouse effect, which would keep the night time warm and the daytime even warmer. On Earth, you just saw that the greenhouse effect raises the average temperature 33 °C. While gases like carbon dioxide do contribute to this effect, the main greenhouse gas is water vapour—and as temperatures rise even greater amounts of it enter the atmosphere, raising temperatures even further.

Early in the Solar System’s history when the Sun was first forming, stellar models indicate that its temperature would have been lower and the radiation received by all the planets was less. It is thought that Venus was likely much more Earth-like at this stage. However, as the Sun warmed, Venus got hot enough to enter a feedback loop, called a runaway greenhouse effect, where increasing water vapour in the atmosphere trapped increasing amounts of radiation, which in turn caused more water to evaporate into the atmosphere, until temperatures everywhere on Venus raised well above the boiling point of water. Recent radar analyses (from 2023 Magellan data reanalysis) confirm that Venus still experiences active volcanism, supporting the idea that internal heat release and atmospheric thickening reinforced this runaway process.

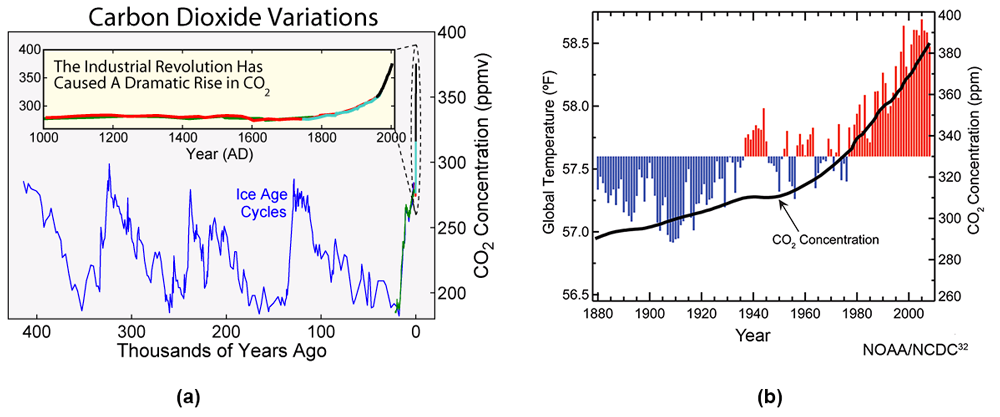

In fact, while the greenhouse effect in Earth’s atmosphere is currently stable, these same models indicate that the Sun will continue to warm as it ages, and that between roughly 1 and 3 billion years from now—a range spanning the transition from a moist-greenhouse state to full ocean loss—long before the Sun’s hydrogen burning stage ends and it bloats to a red giant, engulfing Mercury and Venus, and burning off Earth’s atmosphere as it already has Mercury’s—a runaway greenhouse effect will boil off our oceans as well. While the eventual occurrence of this runaway greenhouse effect is almost certainly inevitable, it is also almost certainly being accelerated by the increased levels of carbon dioxide humans are adding to the atmosphere through fossil-fuel use—an anthropogenic warming that, while not a true runaway greenhouse, amplifies Earth’s natural greenhouse effect (see Figure 7-4).

Learning Activity

Phil Plait’s Crash Course Astronomy video on Venus does an excellent job of explaining the runaway greenhouse effect and the consequences it has had on our sister planet, starting at about 4:15 (before this, he describes observational aspects of Venus from Earth, such as its varying apparent magnitude, its phases, and its transits, then moves on to outline Venus’ physical characteristics such as its temperature, atmospheric pressure, and distance from the Sun). As you watch the video, you’ll learn a number of interesting facts about Venus’ current state and the evidence that supports current scientific theories about its evolution. While the runaway greenhouse effect explains why Venus lost its water, while you watch you should look for answers to the following three questions:

- How has the evolution of Venus’ surface geology differed from Earth’s, particularly in terms of tectonic and volcanic activity, and why?

- Why does Venus not have a global magnetic field?

- Why is Venus’ atmospheric composition so much different from Earth’s? (In particular, where did all the water go?)

The explanation given in this video for why Venus has no global magnetic field does make sense in contrast to what we know of Earth’s magnetic field. However, Venus’ rotation rate is only about one-quarter that of Mercury, where a detectable magnetic field does exist. Furthermore, Venus’ recent volcanic activity indicates that it still has a molten core (supported by radar observations and 2023 analyses of active volcanic vents), and simulations show that its slow rotation rate actually is sufficient to produce a magnetic field through the dynamo effect, the mechanism through which Earth’s and the Sun’s magnetic fields are produced.

So why does Venus not have a global magnetic field? An alternative explanation to the one given in the video goes back to the lack of water. When the liquid water on Venus’ surface vanished, its tectonic plates ground to a halt as well. As you saw in the video, this has since led to a very different surface evolution from Earth. Rather than tectonic plates shifting around and causing mountains to rise up which are subsequently eroded by water and wind over millions of years, Venus goes through resurfacing events in which magma is pumped out through hot spots all over its surface. But Venus’ solid crust must also trap in much more heat than Earth’s, and the current thinking is that this has led Venus to have a more uniform temperature in its interior. We know that the dynamo effect relies on convection, and this could not occur if Venus’ internal temperature is uniform.

In short, the lack of water on the surface of Venus is thought to have affected its geology in such a way that it lost its magnetic field. Subsequently, as you learned in the video, the loss of its magnetic field caused the lighter elements in its atmosphere to be stripped away by the solar wind. In particular, molecules of water vapour were likely broken up by photons through a process known as photodissociation, and the freed hydrogen atoms would have been knocked out by the solar wind. This process continues today, as confirmed by Venus Express and Akatsuki measurements of hydrogen escape from the upper atmosphere.

Although the root cause is thought to have been very different, this final process that stripped Venus’ atmosphere of its lighter elements is also thought to have stripped Mars of most of its atmosphere. Let us turn now to Mars, and investigate the very different processes that are thought to have led to much the same outcome: no liquid water, no tectonic activity, no magnetic field, and an atmosphere that is being stripped away by the solar wind.