Venus is covered in a thick layer of cloud, the atmospheric pressure at its surface nearly 100 times that of Earth’s. These clouds consist primarily of carbon dioxide and droplets of sulfuric acid. Mars has almost no atmosphere, the surface pressure there only one-percent of Earth’s. Venus is half the distance of Mars from the Sun, and coincidentally its closest approach to Earth, at inferior conjunction, is half the closest distance that Mars gets to our planet, when it is at opposition. With its orbit lying inside of our own, Venus goes through a whole range of phases as it orbits the Sun, while Mars, on its orbit further from the Sun, is never less than a gibbous phase. When each planet is closest to us, Venus appears as a sliver while Mars’ phase is full; yet despite this, because of Venus’ proximity to us and its thick, highly reflective atmosphere, it is more than 5 times brighter than Mars. In fact, at its dimmest, when Venus is at superior conjunction—i.e. in its full phase on the other side of the Sun—it is still twice as bright as Mars ever appears to us. Physically, Venus is twice as big as Mars, which also partly accounts for the difference in apparent brightness.

Despite these and more differences between the two planets, there is one important similarity between the two planets which has influenced the history of observations of each in its own unique way: physical surface characteristics on each are not resolvable except through their effect on the planet’s albedo, or reflectivity. Essentially, this means our telescopes can resolve no greater detail on either Venus or Mars than the naked eye can observe on the Moon.

In the case of Venus, we now know that its uniform brightness is due to a thick, uniform layer of mostly carbon dioxide clouds. Evidence for the Venusian atmosphere was only discovered in the mid-eighteenth century, and it was another century before the full ring caused by atmospheric scattering of light when Venus is at inferior conjunction was observed (see Figure 7-1). Due to its atmosphere, little more could be learned about Venus before the properties of electromagnetic radiation were better understood. Radar observations in the 1950s-1970s showed that Venus is actually rotating in the opposite direction of Earth (so the Sun rises in the west on Venus), although this rotation is so slow that a day on Venus (243 Earth days) is longer than its year (225 Earth days). These radar observations also began to reveal large surface features on Venus, and provided the first estimates of its surface temperature. However, it was not until NASA’s Mariner 2 probe reached Venus in December 1962 that the extreme surface temperature above 400 °C was revealed, destroying any prior hope that life might be found on Venus. Subsequent Soviet Venera landers (1967–1985) returned surface images and confirmed the crushing pressure and high temperatures first detected by Mariner 2. High-resolution radar mapping by the Magellan spacecraft (1990–94) later produced a complete topographic map of the planet’s surface.

Mars, on the other hand, due to its thin atmosphere composed mostly of carbon dioxide (≈ 95 %), does exhibit variation in colour due to the variation in its surface albedo. As mentioned earlier in the course, in the early nineteenth century William Herschel discovered the seasonal variation in the size of Mars’ polar ice caps, which he accomplished after measuring Mars axial tilt. In fact, with an axial tilt of 25° and a rotational period of roughly 24 hours, Herschel was able to conclude that the Martian seasons would be similar to the seasons on Earth, although the variation would be more gradual due to Mars’ 687-Earth day (669-Martian day) orbital period.

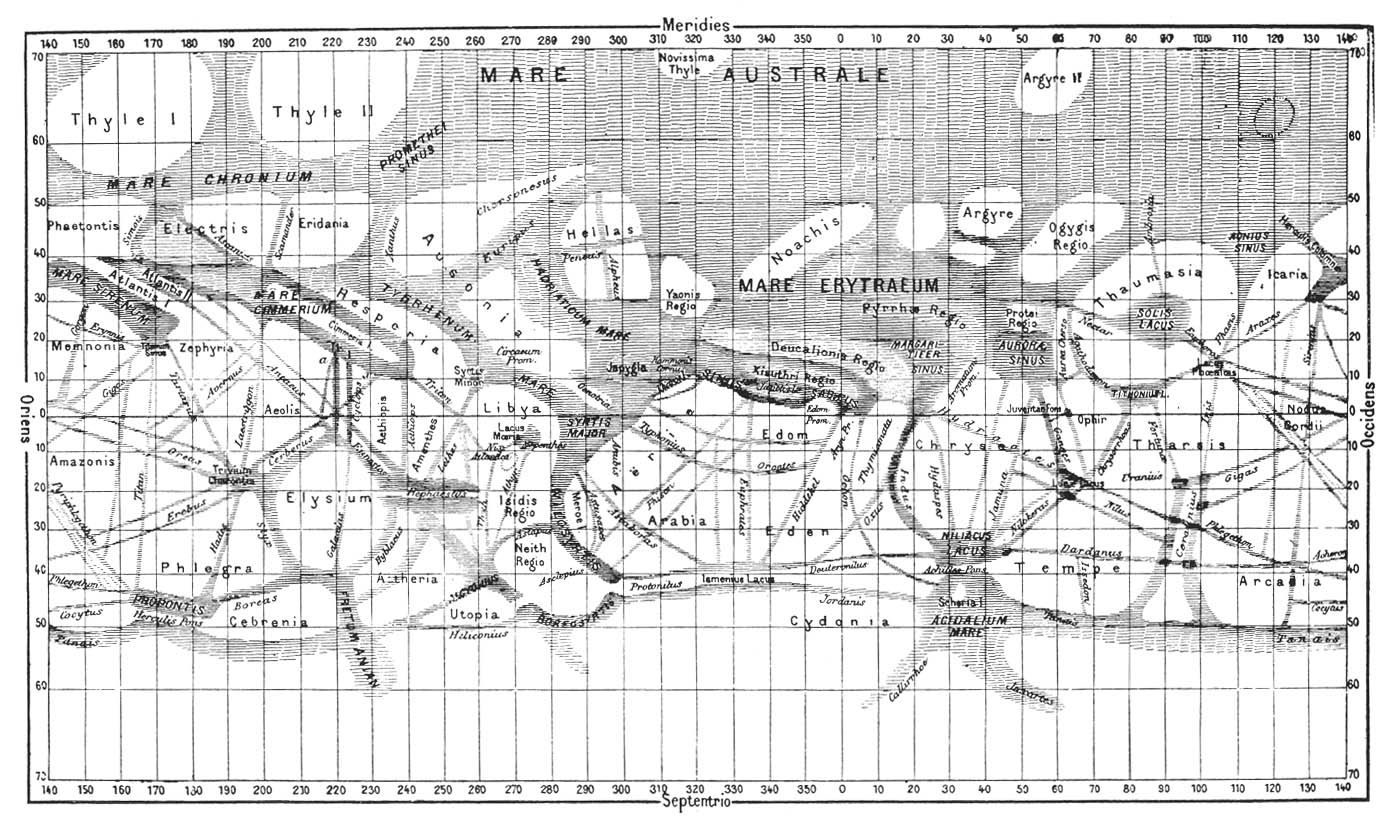

As telescopes improved, a number of interesting discoveries were announced. In particular, in 1877 Asaph Hall discovered Mars’ two moons, Deimos and Phobos, two irregularly shaped objects which may in fact be captured asteroids. In the same year, Schiaparelli began compiling a map of the observable features on Mars (see Figure 7-2; you may recall Schiaparelli’s name from Module 6, as the astronomer who mapped the surface of Mercury in the 1880s). His observation of linear canali, or channels (although the word was often mistranslated) sparked a long-standing debate over the possible existence of a network of canals that had been constructed by Martians. Eventually, these “canals” were understood to be an optical illusion due to the eye’s tendency to draw connections between darker places on the surface.

closest flyby. Source.

Ground-based observations over the following decades indicated that surface temperatures were cooler than on Earth, although still above freezing in places, and upper limits placed on Mars’ atmosphere showed that it must be many times thinner than Earth’s. However, as with Venus, the last vestiges of hope that Mars could be inhabited were only finally dashed when NASA’s Mariner 4 mission reached Mars in 1965. Mariner 4 sent back pictures of a cratered Martian surface resembling the Moon (see Figure 7-3), measured an atmospheric pressure of roughly 0.5% the pressure of Earth’s atmosphere, measured daytime temperatures near –60 °C, with nighttime lows around –100 °C, and found that Mars has no global magnetic field (which, as you’ll see below, is critical to the habitability of our planet). Later orbital data from Mars Global Surveyor and MAVEN revealed strong localized crustal magnetic fields but confirmed the absence of a global dynamo.

Since these early observations of Venus and Mars, and particularly through the data collected by probes we’ve sent to each planet, it has become clear just how special our own planet is. At the same time, we have learned a lot about what makes a planet “habitable”. Modern missions—such as Akatsuki at Venus and Perseverance, ExoMars TGO, and InSight at Mars—continue to refine our understanding of how these worlds evolved.

In order to understand the habitability of our world, we’ve found that it is important to investigate more than just the one place we know of where life has managed to exist, but to explore the mechanisms through which habitability failed on our neighbouring worlds. In this module, you will therefore begin by exploring how Earth manages to maintain its abundance of liquid water, as we understand this to be the special ingredient to the existence of life on our planet. After that, we will move on to examine the situation on Venus, then on Mars, two places we think began much like Earth, but were unable to maintain stores of liquid surface water for two very different reasons.