A common misconception is that the Sun is in the sky during the day and the Moon is up at night. However, the Moon is actually up exactly as much in the daytime as it is at night. The contrast in brightness between the Sun and the Moon is certainly a factor that contributes to this misconception: when both the Sun and the Moon are in the sky, the Sun stands out more. In fact, this compounds with the other major factor that leads to this misconception—viz. the cycle of the Moon’s phases.

From our perspective, the Moon moves eastward through the celestial sphere, roughly following the ecliptic (the Sun’s path) and completing its circuit roughly once a month. In fact, the words “Moon” and “month” have common etymological origins in English and many other languages for this very reason. Since the Sun moves around the ecliptic only once a year (as a result of Earth’s orbit), the Moon circles through the celestial sphere twelve times faster. (Whereas the Moon’s angular speed through the sky is roughly 360°/month, the Sun’s speed is roughly 360°/12 months, or 30° per month). Since the Moon follows roughly the same path, it is at times very close to the Sun and at others (i.e. two weeks later) on the opposite side of the celestial sphere.

When the Moon is on the opposite side of the celestial sphere from the Sun, it is

- up when the Sun is down—i.e. from roughly 6 pm to 6 am—and

- full.

The Moon is therefore at its biggest and brightest when it’s up all night. In contrast, when the Moon gets its closest to the Sun, it is

- up the whole time the Sun is up—i.e. from roughly 6 am to 6 pm—and

- new.

When the Moon is new—i.e. when it’s up all day long—none of it is illuminated.

There are really only a couple of days a month when the Moon actually isn’t visible in the sky because it’s too close to the Sun and only a sliver of light is showing. However, the facts that less of the Moon is visible when it is in the sky during the day, and that the Sun dominates the sky at those times, both contribute to the common conception that “the Moon is up at night and the Sun is up during the day.”

As new moon approaches, the Moon approaches the Sun from the west, moving eastward, and the crescent of light that is visible becomes smaller and smaller. This phase is called a waning crescent. After new moon, the Moon continues its eastward progression through the celestial sphere away from the Sun, and a growing crescent of light, called a waxing crescent, is visible.

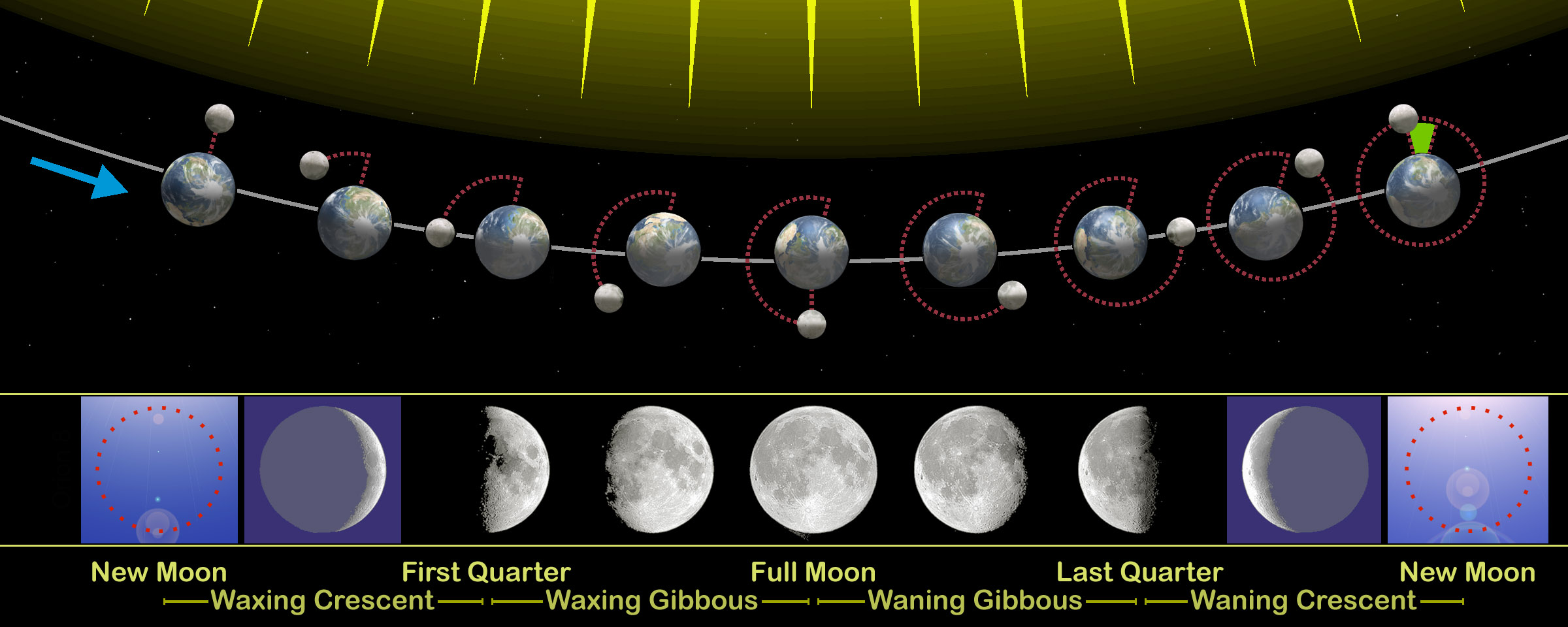

When the Moon is separated from the Sun by 90° in either direction, which occurs about a week before or after new moon, the half of its face that is closest to the Sun is illuminated and the other half is dark. The phase occurring one week after new moon is called first quarter, and the phase occurring a week before new moon is called third quarter. During the other two weeks of the lunar cycle, the Moon is in its gibbous phase. In the week following first quarter, it is a waxing gibbous, becoming full at the end of the week (two weeks after it was new). As it continues around the ecliptic towards the Sun its light begins to wane, so the one week-phase between full and third quarter moon is called a waning gibbous. The full cycle of lunar phases from one new moon to the next is: new moon, waxing crescent, first quarter, waxing gibbous, full moon, waning gibbous, third quarter, waning crescent, new moon.

Learning Activity

The description above explains that the Moon appears in the sky at different times of day or night, at different times of the month. Referring to this description and to Figure 6-2, you now have all the information you need to answer each of the following:

- What time of day is a first-quarter moon visible?

- What time of day is a third-quarter moon visible?

- What time of day is a waxing gibbous moon visible?

- What time of day is a waning gibbous moon visible?

Check your answers by searching the internet!

The sequence of lunar phases, along with the fact that sometimes a new Moon actually moves directly in front of the Sun, blocking its light, has led every culture throughout human history to two conclusions: the Moon is illuminated by the Sun, and the Moon is closer to us than the Sun. In addition, despite the fact that the same (two-dimensional) circular face is all that is visible as the Moon orbits the Earth, its (three-dimensional) spherical shape could be deduced from the shape of the terminator—the line separating the light and dark sides—as sunlight hits the Moon from different angles throughout the month (see Figure 6-1).

We now understand that the Moon follows an elliptical orbit around the Earth once every 27.3 days, which is called its sidereal period. Due to the direction it orbits, we therefore see the Moon circle the celestial sphere in an eastward direction over this period. However, because the Earth also orbits the Sun in the same direction (counter-clockwise when viewed from above the North Pole), the Sun also moves eastward along the ecliptic—albeit at a slower rate—so it takes somewhat longer for the Moon to make up the extra distance and complete a full cycle of phases. The length of time from one new moon to the next, or from one full moon to the next, known as the Moon’s synodic period, is roughly 29.5 days. However, this number varies throughout the year due to Earth’s elliptical orbit.

We also know that the Sun is roughly 400 times further away from the Earth than the Moon (and, remarkably, 400 times larger in diameter so that they both appear to us to have the same size), and that the reason the Moon stays close to the ecliptic is that its orbital plane roughly coincides with Earth’s orbital plane. The Moon’s orbital plane is tilted about 5° relative to Earth’s orbital plane, and because of this tilt, the Moon usually passes above or below the Sun at new moon, rather than directly in front of it. Rather, this is a rare event due to the occasional precise alignment of the Sun, Earth, and Moon, called a solar eclipse, which occurs as the Moon passes through the Earth’s orbital plane (something it does just twice a month) at the very moment that it is new. Similarly, this tilt is the reason why a lunar eclipse does not occur every full moon, but only when the full moon coincides with one of the two occasions in a month when the Moon passes through the Earth’s orbital plane.

Lunar and solar eclipses will be discussed in the next section. For now, before moving on to that, you should take a moment to analyse Figure 6-2 so that you understand the connection between the Moon’s orbit around the Earth, the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, the cycle of lunar phases, and the difference between the Moon’s sidereal and synodic periods.

Learning Activity

There is one last feature of the lunar cycle illustrated in Figure 6-2 that I have not discussed. When observing a crescent moon at twilight, the unlit side of the Moon tends to be visible. Have you ever wondered why that is? Direct sunlight reaches only as far as the terminator, so how is it that we can see the dark side of a crescent Moon at sunrise and sunset? Look up the term earthshine, or more generally planetshine for an explanation of this phenomenon.

Another example of planetshine is shown in Figure 6-3, an image snapped by NASA’s New Horizon’s spacecraft which caught some “Plutoshine” off the dark side of Charon on July 17, 2015.