As noted in the introduction, Mercury goes through a similar set of phases as the Moon, and even occasionally moves across the Sun—a phenomenon which we call a transit. It is interesting to contrast the phases and transits of Mercury with the phases and eclipses of the Moon, which helps to develop a better understanding of each.

Much like the Moon, since the plane of its orbit is tilted relative to the ecliptic Mercury exhibits a full range of phases rather than passing behind and in front of the Sun with each orbit (see Figure 6-8). Specifically, Mercury orbits the Sun once every 88 days with an orbital inclination of 7° relative to the ecliptic. For the most part, due to its orbital inclination Mercury does not cross the Sun’s path.

While Mercury’s cycle of phases occurs much like the Moon’s, there is one notable difference. Whereas the Moon is full at night, when it is on the opposite side of the Earth as the Sun, Mercury is full when it lies behind the Sun, and is therefore up all day. In fact, whereas a full moon is the second brightest thing in the sky, Mercury’s full phase is dimmer than the daytime sky and is therefore not visible from within Earth’s atmosphere. In contrast, the new phases of both the Moon and Mercury occur in similar orientation, when the two bodies are between the Earth and the Sun and are up all day.

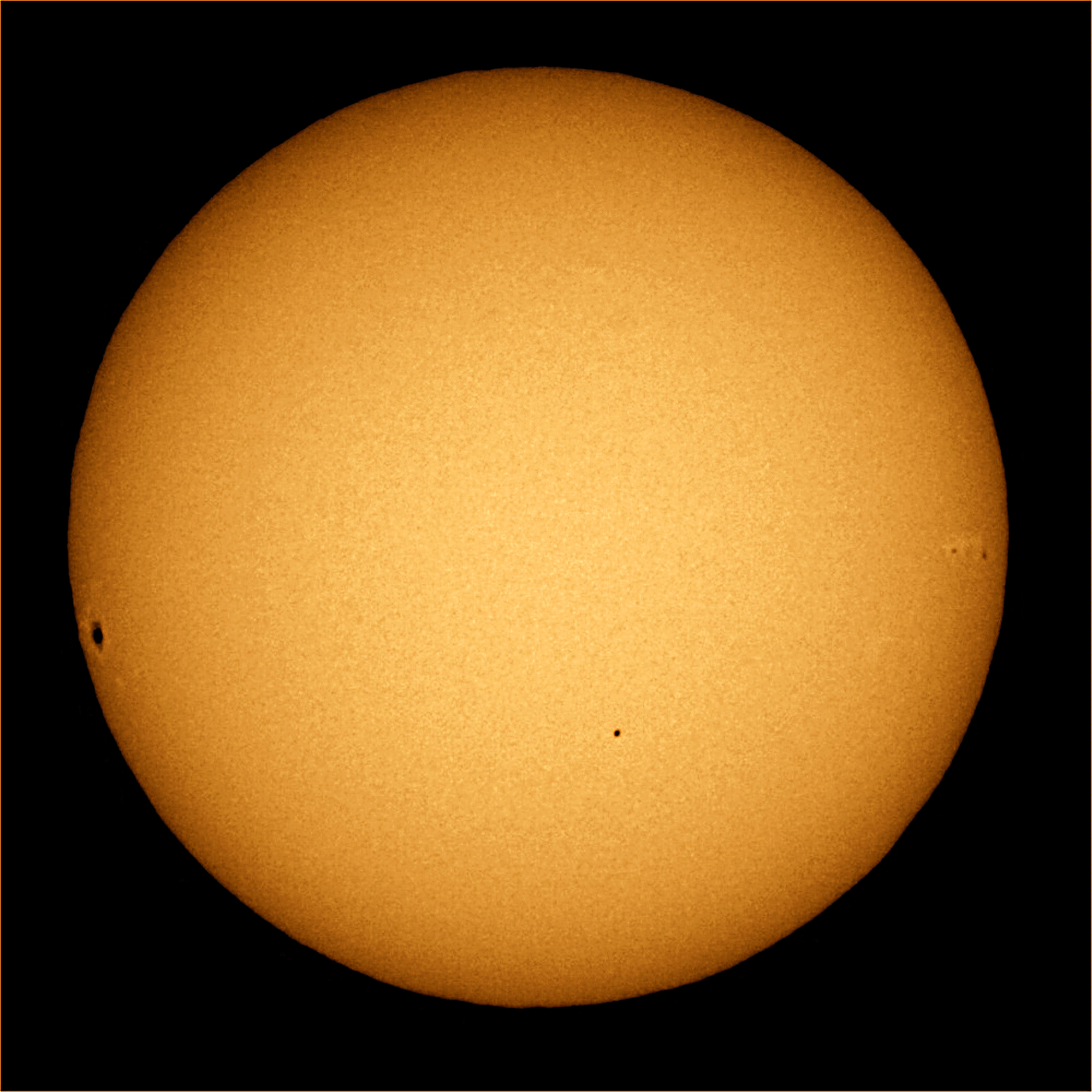

As with the phases of Mercury, there are distinct differences between the eclipses involving the Moon and the transits of Mercury. The obvious one is the amount of the Sun that Mercury blocks when it transits. Since Mercury’s angular diameter ranges from 4.5 to 13 arcseconds, this isn’t much; in contrast to a solar eclipse, a transit of Mercury requires a telescope (with a filter!) in order to be seen (see Figure 6-9).

More interestingly, however, are the differences between the predictability of transits of Mercury and solar eclipses. You may recall from Module 3 that perihelion in Mercury’s orbit advances by an amount that has been measured to great accuracy, as it was one of the key confirmations of Einstein’s general relativity. Specifically, the perihelion advances by ≈1.55° per century (≈5600″/century) when referenced to Earth’s equinox; Newtonian perturbations account for most of this, but the value is of by approximately 43″/century whereas general relativity precisely explains the full observed advance. This means that the line of nodes where the two orbital planes intersect and a transit of Mercury may be visible shifts by only a degree and a half every hundred years. For this reason, in contrast to the Moon, whose orbit advances much more quickly, we can state the two particular months of the year when Mercury transits can possibly occur. Specifically, these are May and November—as they have been ever since the invention of the telescope.

While transits of Mercury occur for similar reasons as eclipses involving the Moon, and therefore can be predicted in a similar fashion, those predictions tell us that transits of Mercury must occur far less frequently than eclipses due to Mercury’s longer orbital period, as well as the fact that a transit can only occur if Mercury passes in front of the Sun. Whereas the Moon goes through a complete cycle of phases every 29.5 days and a solar or lunar eclipse can happen on two of those days during an eclipse season when the Sun, Earth and Moon align, Mercury’s orbital period is 88 days, and a transit can only occur on the day that Mercury passes between the Earth and the Sun. Therefore, whereas 2-3 eclipses typically occur every eclipse season, only about 13-14 transits of Mercury occur in a century. For example, the last one occurred on 11 November 2019; upcoming transits will take place on 13 November 2032, 7 November 2039, 7 May 2049, and 9 May 2052.