So far, we have concentrated primarily on observations of the Moon and Mercury that can be made from Earth. The phases, eclipses and transits we observe result from the relative orientations of the Sun, the Earth, and both of these objects. But it is of interest to us to learn about more than just how either object happens to be perceived due to our vantage point. Indeed, even phases and eclipses, while they are interesting even just from a purely visual perspective, are also intriguing because of the implications they have for the nature of the objects themselves. The Moon’s phases, together with its motion through the celestial sphere, imply that it orbits the Earth at an angle relative to the Earth’s orbit, and that it is not bright all on its own, but is illuminated by the Sun. The fact that we only ever see one side of the Moon implies that it is tidally locked in synchronous rotation about the Earth. By observing eclipses, we know that the Moon has little-to-no atmosphere. Mercury’s phases, on the other hand, together with its motion through the celestial sphere, imply that it is orbiting the Sun. The transits and occultations of Mercury that occur as it occasionally passes directly in front of or behind the Sun confirm this.

It turns out that there is quite a lot that can be learned because we are able to observe these special events from Earth. However, there is also a lot more to be learned about both objects. In fact, as it happens not much of what we currently understand about either object was known before the Space Age hit in the late 1950s. The information that has been gathered by sending space probes to each of these objects has significantly changed what we know about them. And with that said, let us move forward to investigate what else is known about both objects, beginning with the Moon.

The Moon

The surface of the near side of the Moon—the only half we can see from Earth due to its tidally locked orbit—had been carefully mapped already before the 1950s. We knew that the surface generally consists of relatively bright, cratered highlands and smooth, dark “seas,” known as maria (singular, mare). While some of the first astronomers to point telescopes at the Moon thought that the maria might be seas of water (“mare,” pronounced MAH-ray means “sea” in Latin), more detailed observations showed that the maria are sparsely cratered as well. Therefore, they were subsequently understood to be the sites of ancient lava flows. These basaltic plains formed from partial melting of the mantle following large impacts during the Moon’s early history.

Another important set of physical characteristics of the Moon that were known already since the Scientific Revolution—i.e. since observations and Newtonian physics could be used to accurately determine the Moon’s mass and radius—are the Moon’s average density and its size. It turns out that the Moon’s density is only 3.34 g/cm3—far less than the Earth’s 5.51 g/cm3—indicating much lower concentrations of metals than what exists on Earth. In addition to this, the Moon’s size relative to the Earth is one of its most striking physical features. As the relative sizes of our Solar System’s planets and their moons go, the Moon is big—its diameter more than 1/4 that of Earth’s.

In addition to the Moon’s size, density and apparent surface morphology, the fact that it lacks an atmosphere was also evident from the lack of interference with telescopic observations, particularly during solar eclipses. Indeed, due to the Moon’s low density and relatively weak gravitational field it makes sense that it would not hold onto atmospheric gases.

Prior to the Space Age, three competing hypotheses had been put forward which attempted to explain the Moon’s origin:

- The Condensation Hypothesis – the Earth and Moon condensed together from the same cloud of matter.

- The Fission Hypothesis – the Moon broke from a rapidly spinning Earth while it was very young.

- The Capture Hypothesis – the Moon formed somewhere else in the Solar System and was captured by Earth.

All three hypotheses had their strengths. The condensation hypothesis is the most likely scenario for the formation of a moon around a planet, and is thought to account for the formation of many of the moons in our Solar System. However, it is thought to be incorrect for our Moon because it is too large and its different density indicates far fewer metals. The other two hypotheses could account for the size of the Moon and its low metal abundance, but the probability of either occurring is very low. In fact, it turns out that much of what people had thought they understood about the Moon changed when we began sending probes and people out to study it, and today all three of these hypotheses are thought to be incorrect. They have been replaced by the large-impact hypothesis, in which a Mars-sized body (Theia) collided with the young Earth, ejecting debris that coalesced into the Moon.

The first indication of our Moon’s strange origin came when the first images of its far side, taken by the Soviet Luna 3 probe, were sent back to Earth. The surprising discovery that had been made was that the far side of the Moon contains almost no maria. In fact, only 1% of the far side’s surface is covered in maria, compared with 31% on the near side (see Figure 6-10). A possible explanation for this disparity might have been that the Earth has shielded the near side from the same amount of cratering that has occurred on the far side, and that the far side’s maria have therefore been wiped out since they were created. However, this hypothesis immediately falls through. As we’ve already worked out, the Earth’s diameter when viewed from the Moon is only 1.9°, which means the total area of the near side’s sky that is actually blocked by the Earth is only 2.8 square degrees. Even taking into account the Earth’s stronger gravity, it turns out that its ability to act as an effective shield for the near side is negligible.

Explaining the disparity between the amounts of maria on the two sides of the Moon seems likely to be connected to some aspect of the Moon itself, and may even tell us something about its origin. Astronomers therefore needed more information about the Moon. The main source of this information came from NASA’s Apollo missions in 1969-1972, which strategically collected rock samples from different sites on the Moon. Analysis of these rocks indicated that most of the maria formed between 3 and 3.5 billion years ago, with the oldest having formed 4.2 billion years ago. In contrast, rocks collected from the cratered highlands suggest that they were created mainly between 4.1 and 3.8 billion years ago.

The generally accepted explanation of the Apollo data is that after the Moon’s crust had solidified there was a surge of meteorite activity, during the period that formed the lunar highlands, known as the late heavy bombardment. Large impacts during this period are thought to have caused deep fractures to form, so that lava from the Moon’s hot mantle could flow out and fill the large impact basins over the next billion years or so. This explanation accounts for a number of observed features, such as the circular shape of many large maria. The problem then becomes to explain why the late heavy bombardment created lava flows only on the near side of the Moon.

The main piece of evidence that is used to answer this puzzle comes from studying the thickness of the Moon’s crust. Data from NASA’s GRAIL mission show that the Moon’s crust averages about 34–43 km thick, with the far side roughly 15–20 km thicker than the near side. As a result, it is thought that the fractures from heavy impacts on the far side did not reach down to the hot mantle.

The disparity between crustal thickness of the near and far side of the Moon seems to offer a reasonable explanation of why the maria exist on the one side and not the other, but at the same time it adds another problem—i.e. why is the crust thinner on one side than the other? A number of hypotheses have been put forward to explain the difference in crustal thickness, from the existence of two moons early on that collided to form the one we have now, to the possibility that heat from a young Earth effectively evaporated the surface of the near side—a proposal known as the earthshine hypothesis. However, most current models favour asymmetric crystallization during the Moon’s early magma-ocean phase as the main cause of crustal thickness variation.

The currently favoured theory of the Moon’s formation, known as the large-impact hypothesis, has been around since the 1970s and is generally thought to explain a number of observed features, such as the difference between the Moon’s and the Earth’s densities and metal abundances (iron, in particular), the presence of greater amounts of some oxygen isotopes on the Moon than we find on Earth, and, at the same time, the similar abundances of a number of other elements that are found on the surface of each body.

Both the large-impact hypothesis and the earthshine hypothesis are discussed in the Crash Course Astronomy episode on the Moon. In addition to the excellent explanation it gives of each of these, you’ll find that the video provides a helpful review of much of the material covered in this section, plus a description of two additional details about the Moon: the so-called Moon illusion, and the recent discovery in 2009-2010 of an estimated 600 million metric tonnes of water-ice trapped in permanently darkened craters at the Moon’s poles.

Mercury

In comparison to the Moon, we knew almost nothing about Mercury until very recently. One reason for this is that while the Moon is nearby and its features are resolvable with almost any optical device (telescope, binoculars, camera, etc.), Mercury is actually the most difficult of all the naked eye Solar System objects to observe. The other reason is that while the Moon is by far the easiest body in the Solar System to send a probe to, Mercury is actually really difficult to get to due to the fact that it orbits deep within the Sun’s gravitational well. As a result, any probe we send requires a very precise trajectory and must be able to withstand tremendous amounts of radiation.

Despite these obstacles, astronomers had used telescopic observations to determine a few interesting characteristics of Mercury. As previously discussed, Mercury’s orbit was known with great accuracy, the anomalous perihelion precession causing a great puzzle before Einstein solved it in 1915. One of the more famous proposals that had been made prior to Einstein’s explanation—the existence of a hypothetical planet called Vulcan which was supposed to be nearer to the Sun—has a connection to the discovery of Neptune, and will be discussed in Module 9.

Mercury’s elliptical orbit is the most eccentric of all the planetary orbits in our Solar System. As a result, its furthest separation from the Sun (called maximum elongation), which occurs roughly when the line from the Earth to the Sun is perpendicular to the line from the Sun to Mercury, can be drastically different depending on where Mercury is in its orbit. The minimum value, occurring when Mercury is at perihelion, is 18º. In contrast, its maximum elongation at aphelion is 28º. This means that at aphelion Mercury is more than 1.5 times further from the Sun, and receives less than half the radiation from the Sun, than at perihelion.

In contrast to the Earth, where our seasons result from a tilted rotational axis rather than our changing distance from the Sun (Earth actually reaches perihelion in early January), this difference in the amount of radiation Mercury receives from the Sun depending on where it is in its orbit should have important consequences for its seasons. However, before astronomers could really say anything about that, other important factors such as the status of Mercury’s atmosphere and the length of its day also had to be determined.

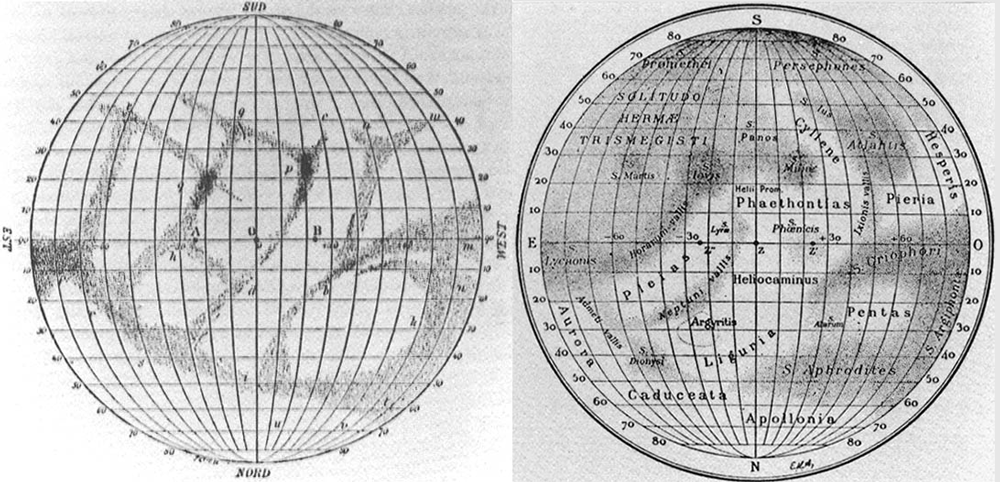

During the nineteenth century, astronomers had already begun to expect little if any atmosphere. In fact, around the turn of the twentieth century astronomers were even able to produce maps of Mercury’s surface, which could be seen due to the lack of atmosphere (see Figure 6-11).

Mapping this surface was far more difficult than mapping the surface of the Moon had been because it needed to be done when Mercury is near its full phase, i.e. when it is close to the Sun and as far as it gets from Earth. Additionally, due to Mercury’s highly elliptical orbit it turned out that the most reliable maps could only be made when Mercury was near aphelion, at its furthest from the Sun. As noted earlier in the module, Mercury rotates 1.5 times each orbit so that the face it presents to the Sun at perihelion alternates from one year to the next. However, due to the difficulties associated with observing Mercury’s surface it turned out that these early attempts to map its surface could only be reliably carried out after an even number of years had passed. As a result, astronomers saw the same face of Mercury whenever they mapped it, and concluded that it was tidally locked into a synchronous rotation, much like the Moon. One side of Mercury was thought to be perpetually illuminated, its temperature rising and falling between perihelion and aphelion as it orbited the Sun, while the other was thought to be in a deep freeze, hidden away in permanent darkness and, due to the lack of atmosphere that was generally presumed, heated only by the planet’s core.

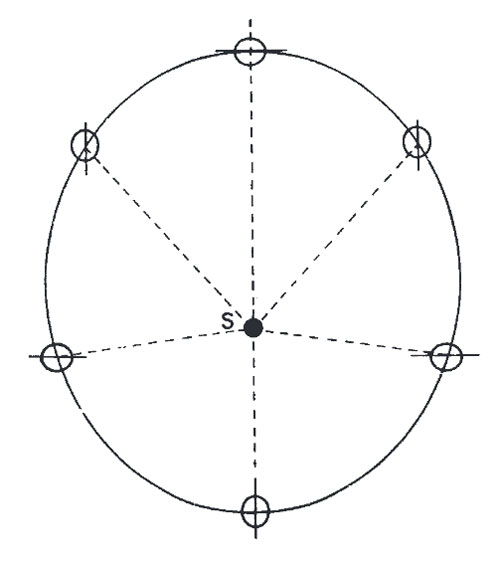

Mercury maintains the same orientation, but its direction reverses. Source: G. Colombo, Nature 5010, 575 (1965).

It therefore came as a big shock when, in 1965, Doppler radar measurements of Mercury’s rotational period did not confirm an 88-day rotational period, the same as its orbit, but a period of 59 days instead. In fact, the Arecibo radio telescope which was used to make this measurement yielded another important piece of evidence. It found that the side of Mercury that pointed away from the Sun was much hotter than it should have been if it never saw radiation.

Later that same year, an Italian astronomer named Bepi Colombo from the University of Padua (the same university that Copernicus attended and Galileo taught at), noted that Mercury could be in a tidally locked, stable synchronous orbit if its rotational period were in fact 2/3 its orbital period, so it would undergo 1.5 rotations with each orbit, alternating which face it presented to the Sun from one perihelion to the next (see Figure 6-12). Colombo’s explanation was confirmed by observations from the Mariner 10 mission, the first successful mission to Mercury which flew past the planet three times in 1974-1975.

In fact, Colombo was also the person who worked out how to get a probe from Earth into an orbit that would bring it past Mercury, and Mariner 10’s trajectory (see Figure 6-13) was based on his calculations. In order to get to Mercury, Mariner 10 used Venus’ gravity to slingshot itself into a lower orbit that brought it past Mercury three times. This was the first use of the slingshot technique, known as gravity assist, in an interplanetary trajectory (you may have seen this technique used, e.g., in The Martian). Since Mariner 10, we have sent only one other spacecraft to study Mercury, in NASA’s MESSENGER mission, where gravity assist was used a number of times before eventually settling in to orbit Mercury from 2011 to 2015. In October 2018, ESA and JAXA launched the BepiColombo mission which will further study Mercury’s surface, interior structure, magnetic field, and magnetosphere.

Nearly all the information we have on Mercury comes from the Mariner 10 and MESSENGER missions. The Mariner 10 mission immediately confirmed that Mercury’s surface is covered in craters and appears much like the Moon’s (see Figure 6-14). Unfortunately, since Mariner 10’s orbit was almost exactly twice that of Mercury’s, the same half of the planet was sunlit during each of its three flybys, so only 40-45% of the surface was mapped.

In addition to providing conclusive evidence of Mercury’s surface morphology and rotation rate, Mariner 10 also discovered that Mercury has an abnormally large iron core, a weak, but detectable magnetic field (~1% of Earth’s), and a tenuous atmosphere. The magnetic field was particularly surprising since Mercury rotates so slowly, so its origin must be very different from the origin of the Sun’s magnetic field (discussed in Module 5), and is likely related to the large iron core. Mercury’s thin exosphere (rather than a true atmosphere), is composed mainly of sodium, potassium, oxygen, and trace hydrogen. It is continually replenished by solar-wind sputtering and micrometeorite impacts that liberate material from the surface. Mariner 10 estimated surface temperatures from about 100 K on the night side to 450 K on the day side, but MESSENGER later measured highs near 700 K (430 °C) directly under the Sun.

Following the success of the Mariner 10 mission, little else was learned about Mercury for more than 30 years until MESSENGER made its first flyby in 2008. The spacecraft made two more flybys before it could finally be inserted into orbit in 2011. The original mission was supposed to last one Earth year, or four Mercury years/two Mercury days. However, due to an ingenious engineering trick called solar sailing, the MESSENGER team was able to extend the mission to a total of four Earth years, during which it was able to orbit at altitudes far lower than anticipated. After snapping more than 250,000 pictures of the planet, exploring details of its rich volcanic history, determining that its surface temperature directly beneath the Sun actually gets as high as 700 K, and discovering that despite the extreme temperatures at its equator, Mercury’s polar craters contain not only 1015 kg of water ice, but even organic materials, MESSENGER finally crashed into Mercury’s Jokai crater, just north of the Shakespeare basin, on April 30, 2015.

The joint ESA–JAXA BepiColombo mission, launched in 2018, has since completed multiple flybys of Mercury and is expected to enter orbit in 2026, where it will build on MESSENGER’s discoveries by mapping the planet’s magnetic field, surface chemistry, and interior structure in unprecedented detail.

Details of the MESSENGER mission and many of its important discoveries are discussed by the MESSENGER team in the following video, Making Mercury Whole.