Predicting eclipses

As noted already in the previous section, the reason why the Sun is not eclipsed every new moon, and the reason why the Moon is not eclipsed every full moon is that the Moon’s orbital plane is tilted 5° with respect to Earth’s. If you took 2-cm key ring and threaded it onto an 8-m wide hoop, then tilted the key ring (in any direction) so that the two-dimensional plane defined by it was tilted 5° with respect to the plane defined by the 8-m hoop, you’d have a pretty good model of the Earth’s and the Moon’s orbits.

At this scale, the Sun’s diameter would be 3.72 cm (that’s larger than the Moon’s orbit!) and the Moon would be less than one-tenth of a millimetre. However, as noted in the last section, since the Sun is both 400 times larger than the Moon and located 400 times further away, if you put a 3.72-cm wide ball in the centre of the big hoop and you found a grain of sand 0.09 mm wide and fixed it to the key ring, then placed a tiny camera in the centre of that key ring, the camera would see that ball and that speck of sand as being the same size.

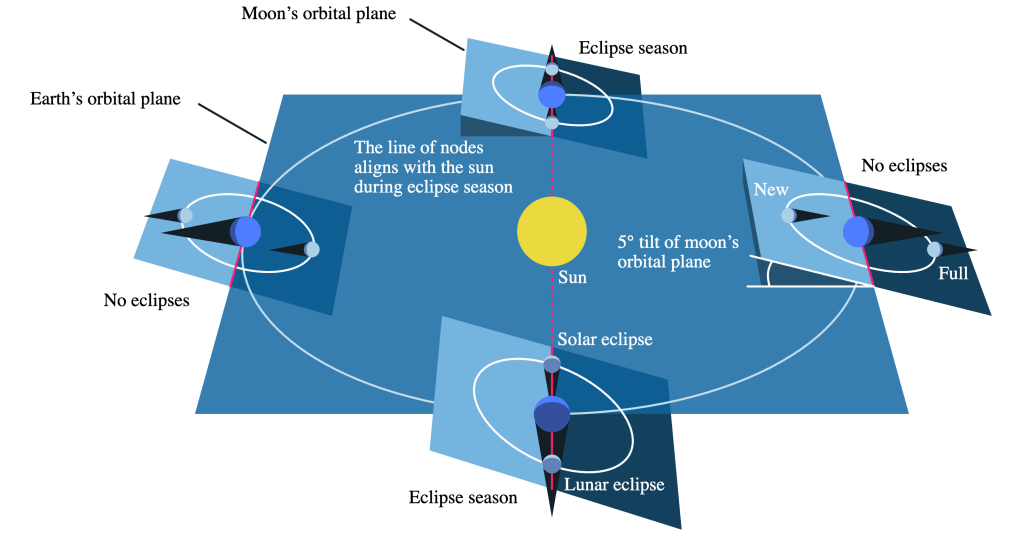

Both the Moon and the Sun are about 0.5° wide from our perspective on Earth (which is how wide the ball and the grain of sand would appear to the camera in your model), so the 5°-tilt in the Moon’s orbital axis is normally more than enough to bring it above or below the line connecting the Sun and the Earth. However, there are two times each year when the Moon’s orbit does pass through that line. Let’s think about how that works (refer to Figure 6-4 below for a visual).

First of all, note that the Moon’s orbit passes through the plane of Earth’s orbit in two places. This means that the Moon crosses the ecliptic twice a month. These two points are called nodes. The line along which the Moon’s orbital plane intersects the Earth’s orbital plane is called the line of nodes. If the line of nodes points towards the Sun (which happens twice a year) at the same time that the Moon happens to be at one of the nodes, then an eclipse will occur. In other words, an eclipse occurs when the Moon is either new or full, at either of the two times in a year when the line of nodes points towards the Sun.

Now, judging from Figure 6-4, it should be fairly easy to predict when an eclipse could possibly occur. Since the line of nodes appears to be fixed in space, you might expect eclipses to occur at the two times of the year that the line of nodes points to the Sun, whenever the Moon happens to be new or full. However, there is actually a slight complication in that the Sun’s gravitational pull causes the Moon’s orbit to precess. As a result, the line of nodes slowly regresses westward, completing a full cycle roughly every 18.6 years, and the nodes move westward about 19.4° each year. When combined with the Sun’s 365-day eastward circuit around the ecliptic, this results in a 346.6-day eclipse year.

Once you’ve observed one eclipse, it’s actually easy to predict when the next will occur. All you need to know is that eclipses can possibly occur every 346.6/2 days after that date, whenever there is a new or full moon.

When a new or full moon happens during an eclipse season, there will be an eclipse. So you may be wondering why you don’t see more eclipses? If there is a 1-in-15 chance that the Moon’s phase will be right for an eclipse when it reaches a node, shouldn’t this mean there should be an eclipse every seven years or so? In fact, given that the Sun moves only about 1° along the ecliptic each day, that the Sun and Moon are both 0.5° in the sky, and that the Moon’s orbit is only tilted 5°, shouldn’t there be a decently long period twice a year when the line of nodes points near enough towards the Sun that an eclipse will occur, significantly improving your odds?

Let’s work this out more mathematically. Referring to Figure 6-4, it should be apparent that the Moon moves from a node on the ecliptic to 5° above or below it every 1/4-year, or roughly 90 days. This means that, on average, the Moon moves roughly 0.05° per day from the ecliptic. Therefore, given the Sun’s and Moon’s angular diameters, this implies that there should be almost 20 days (10 approaching, 10 leaving) every eclipse season (i.e. twice each eclipse year) when an eclipse can occur if the Moon is new or full.

An eclipse is therefore guaranteed, and normally more than that will occur, on two different occasions each year. In fact, if you explore NASA’s eclipse web site, you’ll see that this is the case. But then, this begs the question, why don’t we see more eclipses?

The answer to that question depends on a lot of factors. For one thing, the Moon is technically only “full” or “new” in an instant. Since the Moon’s motion across the sky is fairly quick (360°/27.3 days, or a little over 0.5° per hour), eclipses don’t tend to last very long when they do occur. Perhaps during an eclipse season the Moon is actually technically “full” at noon where you live, so someone on the other side of the world gets to enjoy a lunar eclipse. On the other hand, it may be cloudy at a place where it would be visible, so nobody gets to see the event. That’s another reason why we tend to miss a lot of eclipses—clouds.

Perhaps the most significant reason, however, is the size of the shadow that is cast. In order to see a solar eclipse, you need to be standing in the new moon’s shadow; and in order to see a lunar eclipse, you need to see the full moon pass through the Earth’s shadow. And in fact, the manners in which shadows are cast during lunar and solar eclipses are different enough from one another that we will treat each of them in a separate section.

Solar eclipses

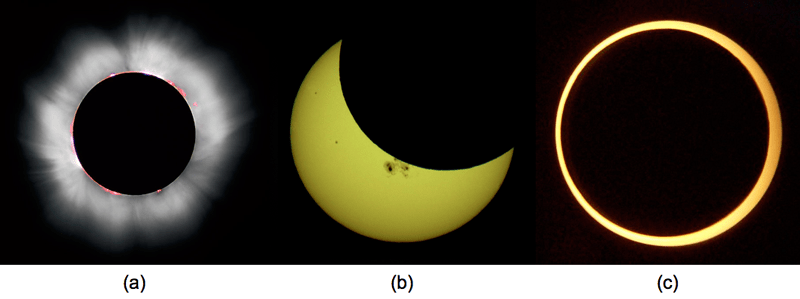

The different types of solar eclipse are total, partial, and annular (see Figure 6-5). The determination of which one of these will be seen at a particular location on Earth when a new moon occurs during eclipse season depends on one thing: the orientation of that location within the Moon’s shadow.

All shadows are broken up into two parts: the umbra and the penumbra (literally, “shadow” and “almost shadow”, in Latin). The umbra is the part of the shadow that is not touched by a source of light, and the penumbra is the part where some of the source is visible. An image depicting the locations of the umbra and penumbra in the Moon’s shadow during a solar eclipse is shown in Figure 6-6.

Within the umbra, light from all around the edge of the Sun is blocked by the Moon from reaching the Earth, and the part of the Earth that falls into this part of the shadow will see a total solar eclipse. In the penumbra, part of the Sun is blocked from view on Earth, but the opposite edge is clearly visible. Within the penumbra, a partial solar eclipse is visible.

An annular solar eclipse occurs as a result of the fact that the Moon’s and the Earth’s orbits are not circular, but elliptical. Because of this, the Moon’s angular diameter viewed from Earth does at times end up significantly smaller than the Sun’s. When a relatively small Moon passes in front of a larger Sun, a ring of sunlight is visible around it. The technical name for this ring shape is an “annulus”, so this type of eclipse is called annular.

Now, as you can see in Figure 6-6, the part of the Moon’s umbra that touches the Earth is really very small. This should actually make sense if you think about the fact that the angular diameters of the Sun and the Moon are roughly the same, and you consider what you know of parallax. Specifically, you should recall that when observing an object at a distance r, an angular parallax shift

θ (radians) = d/r

is introduced by moving a distance d.

Learning Activity

Given that the Moon’s distance from Earth is roughly 380,000 km, determine how far you would have to travel from the location where a total solar eclipse is visible if you wanted to shift the Moon by one-one hundredth of its angular diameter and observe only a partial solar eclipse. You can assume that the Sun is far enough away that no noticeable parallax shift will be introduced.

Click to Reveal Answer

If you look back to Figure 6-5, you’ll notice that in the images of the partial and annular solar eclipses, the Sun appears to be a circle with a distinct edge. This edge marks the the 5777 K surface of the Sun’s photosphere—the dense, opaque layer from which the Sun emits blackbody radiation.

The surface of the photosphere is the brightest part of the Sun that we can see, so as long as it is visible we see nothing else (imagine holding a candle up next to a spotlight; distant observers would see only the spotlight). This is also the reason why the sunspots in the partial eclipse image appear dark; they’re cooler and darker than the surrounding photosphere, so they appear dark alongside it.

However, we know from Module 5 that the Sun is not a perfect blackbody; that there are emission and absorption features in its otherwise blackbody spectrum. The absorption lines are due to elements in the photosphere, but the emission lines must come from something else. Again from Module 5, we know that these lines are caused by the presence of hot gas in which electrons absorb sunlight that was not originally directed towards us, but then emit that light in our direction, adding to the intensity profile at specific wavelengths as electrons drop down to lower energy orbitals.

These emission lines come from the Sun’s atmospheric layers, called the chromosphere and corona. They are less luminous than the photosphere, and can therefore be seen (along with the prominences that are ejected through the Sun’s very active magnetic field) only during a total solar eclipse, when the entire photosphere is blocked from view (see Figure 6-5 a).

Finally, it must be said that although solar eclipses are visually spectacular, if you ever find yourself in one of the small regions of the globe where one is visible during the two eclipse seasons of the year, and if the sky happens to be clear, you should not look at it. As you saw in the last module, the Sun emits a tremendous amount of light—1370 W/m2 at the Earth—and if you look directly at it, it can be very damaging to your eye. In particular, if you’re looking up at a dark total solar eclipse, allowing your pupil to dilate, when the first sliver of photosphere peaks out it can permanently damage your eye. Protective eyewear is always available wherever there are solar eclipses to see, and it’s best to take this precautionary measure when viewing one.

Lunar eclipses, on the other hand, are a whole different story. You can look at them for hours!

Lunar eclipses

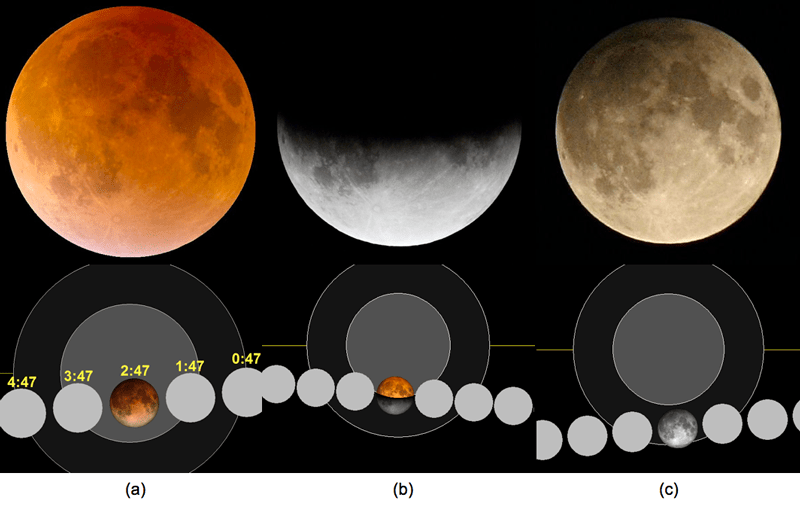

When a full moon passes into the Earth’s shadow, the sunlight that would normally illuminate it is cut off and the Moon darkens in a lunar eclipse. If the Moon fully enters the Earth’s umbra, it is a total lunar eclipse; if the Moon only partly enters the Earth’s umbra, it is a partial lunar eclipse, and if the Moon enters the Earth’s penumbra, it is a penumbral lunar eclipse (see Figure 6-7).

each eclipse, with the Earth’s umbra in grey surrounded by its penumbra in black. Source: a image, a map, b image, b map, c image, c map.

There are a number of notable differences between the lunar eclipses shown in Figure 6-7 and the solar eclipses in Figure 6-5: a total lunar eclipse is red, rather than totally blocked out; the partial lunar eclipse looks more like one would expect, as the eclipsed part of the Moon is dark; and the penumbral eclipse is quite unimpressive, with only a faint dimming at its maximum on the side closest to the umbra. These differences are explained by contrasting the Earth’s shadow (illustrated in the bottom panel of Figure 6-7) with the Moon’s (illustrated in Figure 6-6).

First of all, note the difference between the size of the Moon’s umbra relative to the size of the Earth (in Figure 6-6), and the size of the Earth’s umbra relative to the size of the Moon (in the bottom of Figure 6-7). Since the Earth is much larger than the Moon, it casts a shadow that is actually larger than the Moon, whereas the Moon’s shadow—particularly its umbra—is much smaller than the Earth. Another way of thinking about this is that whereas the Sun and Moon are roughly the same size in the Earth’s sky, if you were standing on the Moon the Earth would appear much larger than the Sun. In fact, whereas the Sun should also have an angular diameter of 0.5° when viewed from the Moon, the Earth’s angular diameter should be almost four times that.

Learning Activity

Check this value using θ (radians) = d/r, where d should be the Earth’s diameter and r should be the Earth-Moon distance.

Click to Reveal Answer

Because the Earth’s umbra is larger than the Moon, when the Moon happens to pass through it no direct sunlight reaches its surface. However, rather than appearing black, the Moon turns a copper red during a total lunar eclipse because Earth’s atmosphere effectively acts like a lens, refracting red sunlight onto it. Alternatively, when viewed from the Moon the same configuration results in a solar eclipse, but with the Earth’s atmosphere glowing red through refracted sunlight, as witnessed during the Apollo 12 mission.

During a partial lunar eclipse, the part of the Moon that falls within the Earth’s umbra appears dark rather than red because the red glow that we normally see during a total eclipse is too dim in contrast to the bright side that falls in the Earth’s penumbra, from where the Sun is only partially eclipsed. Similarly, a penumbral eclipse which does not reach the Earth’s umbra at all is not much dimmer than a full moon, as it is always directly illuminated by part of the Sun.

While solar eclipses are only visible from a small part of the Earth, lunar eclipses are observable from the entire night time side of the Earth, wherever there are no clouds. Therefore, lunar eclipses are much more commonly observed than solar eclipses.