The previous section covered the basic components of an atom without going into either the specific properties of the structure of an atom of a given element, or the way that those properties are able to be observed—say, by an astronomer looking at the light from a distant star and wanting to determine its chemical composition. It turns out that just by looking at the light from any object, it is possible to determine whether the gas is opaque or rarefied, what its temperature is, and often what elements it is composed of.

Explaining how this works requires both knowledge of the basic structure of atoms and an understanding of how that structure affects the features of the spectrum that can be observed. In fact, historically it was the study of different spectral features, their classification and the discovery of certain empirical and physical laws used to explain them, that finally led to the modern physical theory of atomic structure. Let us now follow a similar route to describing the basic structure of an atom and the way we think that explains the observable features of an object’s spectrum, beginning with a general features of spectra that were initially observed.

Kirchhoff’s Three Laws

The science of spectroscopy began with the realisation, by Newton and others in the 17th century, that white light can be dispersed into a spectrum covering a range of wavelengths. However, the first major breakthrough came only at the beginning of the 19th century, when the German optician Joseph von Fraunhofer invented the spectrograph. His spectrograph was a significant improvement on the prisms that had previously been used, as it both improved the spectral resolution that could be observed and it enabled the intensity of light at different wavelengths to be quantified.

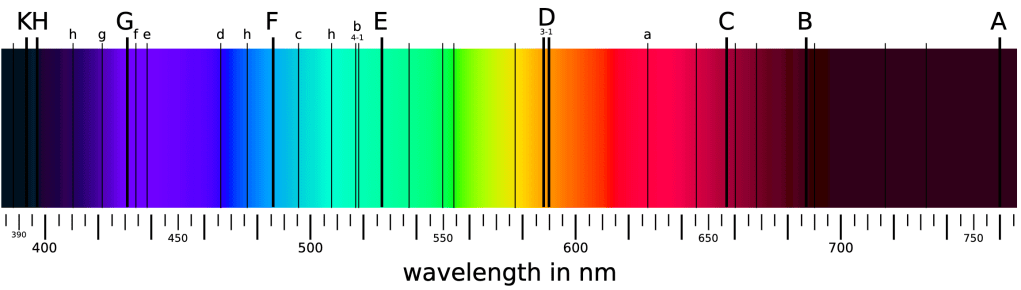

With his spectrograph, Fraunhofer was able to observe dark lines in the spectrum of the Sun (see Figure 5-3). These lines are still known as Fraunhofer lines, or else as absorption lines for physical reasons that will become clear shortly.

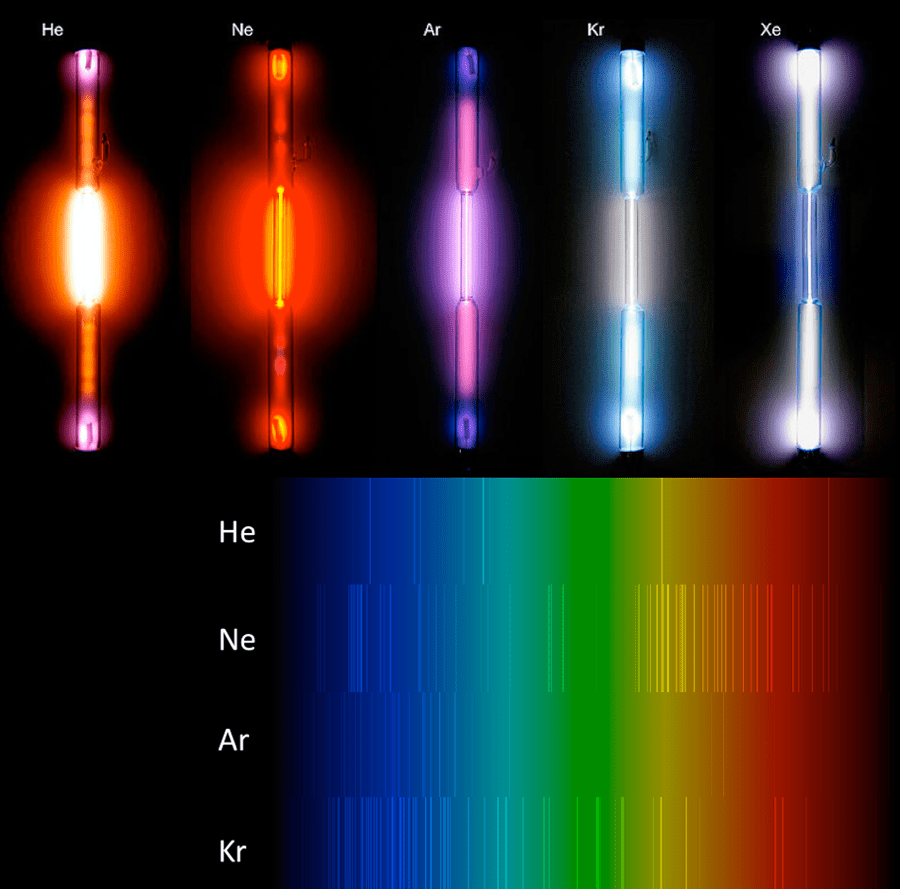

Subsequent studies with the spectrograph showed the spectrum of a diffuse gas to be somewhat inverted from the absorption spectrum of the Sun. Such a spectrum is in fact almost completely devoid of light, but with bright lines observed at discrete wavelengths (see Figure 5-4).

In contrast to this type of spectrum, called an emission spectrum for reasons discussed below, even with the improved resolution of the spectrograph objects like red hot irons were found to exhibit perfectly continuous spectra (i.e. like the Sun’s spectrum, but without Fraunhofer lines). Furthermore, if such an object actually was red hot, the spectrograph showed that the intensity of the spectrum continuously varied over a range of wavelengths, with its most intense light coming from the red part of the spectrum.

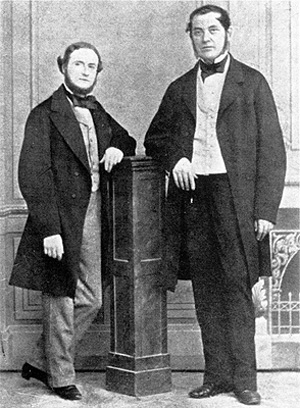

By the 1860s, a few general rules relating to the generation of the two types of spectral lines had started to emerge. In particular, in 1959 German scientists Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff began a systematic study of the characteristic spectra of heated gases. They found that when light passes through a gas, the radiant light that gets scattered has a characteristic emission spectrum which is particular to the element in the gas (see Figure 5-7). In contrast, already in 1853 the Swedish physicist Anders Jonas Ångström had postulated that the characteristic lines in the emission spectrum of a particular gas element are the same as the absorption lines that would be measured in a light source observed to pass directly through the same gas.

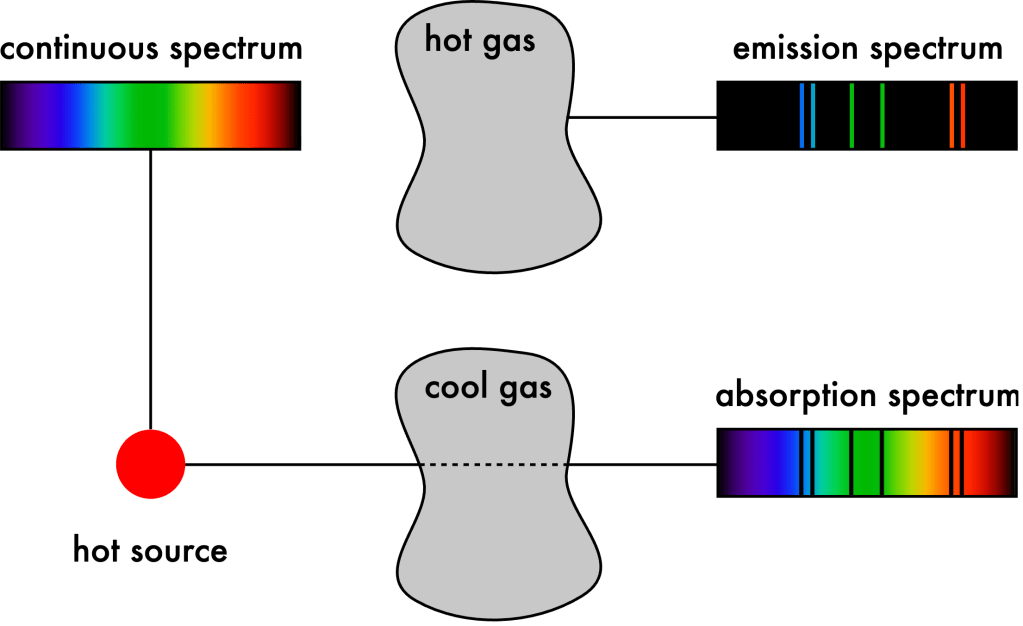

Building on these pioneering works, in the 1960s Kirchhoff published three laws of spectroscopy differentiating between how these various spectra are generated (see Figure 5-8):

- An opaque body emits a continuous spectrum (Figure 5-5).

- A hotter, rarefied gas emits an emission spectrum (Figures 5-4 and 5-7).

- A colder, rarefied gas in front of a hotter, opaque body produces an absorption line spectrum (Figure 5-3).

Heat and Radiation

With the advances in spectroscopy that followed Fraunhofer’s invention of the spectrograph, the stage was finally set to begin understanding the link between heat and energy, and the manner in which a continuous spectrum is produced. This discovery turned out to be one of the most influential in the history of physics: it was the key that unlocked the photoelectric effect and the quantum structure of the atom, which, in turn, finally explained the peculiar emission and absorption features that we now use to determine the chemical compositions of astronomical objects.

The explanation of the continuous spectrum which was finally given by Max Planck in 1900, followed the discovery of two important empirical laws which will be described in the next section. The first relates the amount of radiation that an opaque object emits over all wavelengths to its temperature, and the other relates the wavelength of peak intensity to the object’s temperature.

The amazing thing about both of these laws is that neither one has any dependence on the chemical composition of the “opaque object”. In fact, neither does the radiation law that Planck later discovered. The only requirement is that its surface is dense enough, without any rarefied gas surrounding it, that its spectrum does not exhibit any absorption lines. All such objects, regardless of chemical make-up, emit a continuous spectrum of radiation, the properties of which depend only on the object’s temperature.

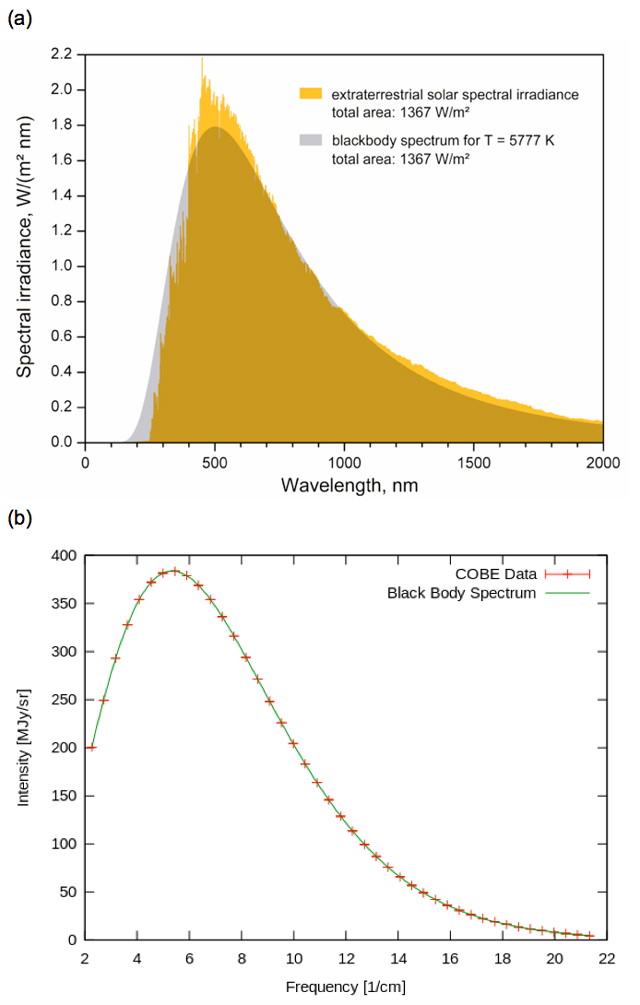

In order to understand these important results, we first need to say something about temperature and heat, and their connection to continuous spectra. Temperature is the measure of the heat, or thermal energy, defined by the movement of atoms within a substance. An object with no thermal energy—i.e. no atomic motion whatsoever—has a temperature of zero. This temperature is often called absolute zero. Likewise, any object whose atoms are moving has thermal energy and therefore nonzero temperature. In gases, individual atoms move around quite freely, whereas in a solid object atoms maintain a fixed structure, so the individual atoms vibrate. The scientific unit for temperature, called the Kelvin temperature scale (K), describes absolute zero as occurring at 0 K and, e.g., the freezing point of water (0 °C) as roughly 273 K. The surface temperature of the Sun turns out to be 5777 K.

Knowing what heat is, is the first step to understanding why an object with a particular temperature emits a continuous spectrum of electromagnetic radiation. The next is to begin looking at the particular details of this radiation spectrum.

Let’s start with things you’re very familiar with. Consider your body, for instance. A human body has nonzero temperature, and therefore should emit a continuous spectrum of radiation according to all that has just been stated. We are certainly able to see people when it’s bright out. However, if you’ve ever been somewhere very dark you know that humans apparently do not glow. It turns out that the reason why we don’t see each other glowing is that the radiation we all emit peaks in the far infrared and is effectively zero at visible wavelengths. The laws we are coming to describe this.

In fact, the light that you see whenever you look at another person or anything else that is illuminated is scattered light, not thermal radiation. It is the portion of incident light that does not get absorbed by the object. A key concept that you’ve frequently encountered in the last two modules is that all the matter you can see in the world is composed of electrically charged particles. Light, being electromagnetic radiation, interacts with those particles and gets scattered in all directions. However, many objects also effectively absorb light at particular wavelengths. A leaf appears green because it predominantly scatters green light while effectively absorbing light at other wavelengths. Your skin is whatever colour it is because it absorbs certain wavelengths of light and scatters the light that you see. Cast iron appears black because it effectively absorbs nearly all incoming light.

In 1860, Kirchhoff first used the term blackbody to describe an ideal object which absorbs all radiation incident upon it. This name refers to the fact that a blackbody scatters no light, and therefore normally appears black at visible wavelengths. Cast iron is an excellent real world-approximation of a blackbody.

If you leave a cast iron pan out in the Sun, it heats up quickly as the atoms it is composed of absorb sunlight. Left to absorb the maximum amount of sunlight on a clear summer’s day, a cast iron pan can get get to be nearly 100°C (you will demonstrate this below). However, much like your body, you still would not see a cast iron pan in the Sun ever begin to glow.

The reason a (nearly) perfect absorber that is exposed to a constant source of radiation will not heat up indefinitely, is that in order for an object to be a (nearly) perfect absorber of radiation, it must also be a (nearly) perfect emitter. Once it reaches a certain equilibrium temperature, a cast iron pan in the Sun therefore emits as much radiation as the incident sunlight it receives—only it emits it in a different form, as a continuous spectrum with a characteristic distribution of intensities that depends solely on the object’s temperature. This thermal radiation is called blackbody radiation because it is the characteristic radiation of a blackbody.

The blackbody radiation emitted by a cast iron pan left in the sunlight is most intense in the infrared, for instance. However, if that pan is thrown in a fiery kiln it eventually becomes hot enough to emit detectable amounts of visible radiation and glows red. When this first occurs, its peak emission is still in the infrared, but its continuous spectrum contains an intense enough visible signal that our eyes can detect it. As its temperature rises, however, the peak can enter the visible part of the spectrum and the blackbody radiation eventually glows more orange, then white, as the intensity of light from all wavelengths becomes appreciable.

Blackbody Radiation: Describing the Phenomenon

As noted already at the start of the previous section, the blackbody radiation phenomenon was explained by Planck in 1900. But before Planck explained it, others discovered the useful descriptions of its physical properties that paved the way to Planck’s explanation.

A set of blackbody curves whose shapes are determined by Planck’s law are shown in Figure 5-9. This figure plots the amount of energy per unit surface area emitted by a blackbody over a range of wavelengths; i.e. the black body’s continuous thermal radiation spectrum. (Note that this is just another way of looking at an object’s spectrum from what you are by now used to. Rather than displaying a band of colour with varying intensity, Figure 5-9 shows more quantitatively how the intensity varies with wavelength). The curves in Figure 5-9 are generated from the mathematical expression of Planck’s radiation law, which agrees precisely with observed continuous spectra of blackbodies with any temperature, so this figure is useful in discussing the two empirical laws that preceded Planck’s discovery.

First of all, note that nothing at all needs to be said about the chemical composition of the blackbody. In fact, the only requirement is that its surface is dense enough, without any rarefied gas surrounding it, that its spectrum does not exhibit any absorption lines. All such objects, regardless of chemical make-up, emit radiation in the form of such a continuous spectrum which depends only on their temperature (see Figure 5-10).

Looking at the blackbody curves in Figures 5-9, another notable feature is that as a blackbody’s temperature increases, so does its total energy output per unit area. First of all, let’s explain that “per unit area”. It simply means that if you measured the blackbody spectrum of a bowling ball at room temperature (that is, the intensity of infrared radiation it emits over all wavelengths) and divided by its surface area, you’d see the same curve as you would if you measured the spectrum of a marble in the same room and divided by its surface area. The bowling ball emits more radiation because it’s bigger, but “per unit area” their blackbody spectra would be the same.

So, as noted, the blackbody curves in Figure 5-9 indicate that a blackbody’s total energy output—that is, the sum of all the radiation it emits over all wavelengths, equal to the area under each curve—increases with temperature. The total energy output per second—i.e. the total power output—is called an object’s luminosity, L, and is measured in units of Watts, W. In the case of a blackbody, there turns out to be a particularly simple relationship between this value and the body’s area, A, and temperature, T, viz.

where σ = 5.7 x 10-8 W/(m2⋅K4) is a constant of proportionality between the blackbody’s luminosity per unit area and its temperature to the fourth power. Therefore, as a blackbody’s temperature increases, its luminosity per unit area goes up exponentially. This relationship was discovered in 1879 by Josef Stefan based on empirical observations, and in 1884 it was derived by Ludwig Boltzmann through theoretical considerations using thermodynamics. It is therefore known as the Stefan-Boltzmann law, and the constant σ (denoted by the Greek letter “sigma”) is called the Stefan-Boltzmann constant.

The next step in the discovery of Planck’s law came from his colleague, Wilhelm Wien, who in 1896 determined an empirical relation between a blackbody’s temperature and the wavelength of its peak spectral intensity, λmax—viz.

λmax⋅T = 0.0029 m⋅K.

This relationship, known as Wien’s law, says that as a blackbody’s temperature increases the wavelength at which it radiates most intensely decreases (or, frequency increases) by the same amount, so the product of the two remains constant. Thus, e.g., when cast iron is thrown into a kiln and its temperature increases, its blackbody spectrum shifts by equal degrees from the long-wavelength infrared, to a visible glow.

Learning Activity

Explore the relationships between temperature and colour, luminosity, and peak wavelength through the Blackbody Spectrum PhET simulation.

Planck’s Explanation

Wien recognised right away that his formula is only valid for high frequency blackbody radiation, as it fails to accurately represent experimental data at longer wavelengths. Planck sought a better description, and in 1900 produced a formula that fit the observational data for all wavelengths.

With this accurate formula in hand, the job then became to derive it theoretically. Planck’s derivation began with an idea that the energy of the blackbody exists either as radiation that could freely move about, or that which was bound up in “oscillators” that vibrated with frequency ν, and were capable of absorbing and emitting radiation. By statistically adding up the energies of all these oscillators and allowing for a continuous distribution of frequencies, he hoped to derive his formula.

In order to perform his calculation, Planck used a statistical technique that had been developed by Boltzmann. In order to add up all possible energies, he actually needed to begin with an assumption that there were finitely many of them. Then, he’d use calculus to make that finite number infinite. So, Planck began with an assumption that the oscillators could have only discrete energy values, given by

E = nhν,

where n is an integer and h is a constant. His plan was that by eventually making h infinitesimally small (which is calculus language for setting it to zero) he would arrive at the expression for a continuous distribution of oscillator energies.

No such luck.

This approach actually led Planck to the expression he wanted for the blackbody radiation curve—i.e. the one he already knew worked—but he could only get there if h remained a finite number. Specifically, by comparing his actual formula with Wien’s law he found that h, which is now known as Planck’s constant, is

h = 6.626 x 10-34 m2⋅kg/s.

Due to the approach he took to deriving his formula, this meant that the energies of all the oscillators would have to be integer multiples of some finite minimum energy,

E0 = hν,

with a particular frequency ν. Planck was not happy about this result, and tried to find a way around it but came up empty.

According to modern physics, Planck’s result actually does provide the correct explanation despite the fact that his calculation didn’t work out as intended. Much like Kepler, who had spent so much time trying to piece together spheres and Platonic solids only to discover the elliptical orbits of a gravitational field, Planck derived an accurate description of nature that turned out to be something other than he had intended. Once again, the key to success was ensuring that the formula fit the evidence that was known, rather than trying to force the data to bend to his ideas.

And just as Kepler’s laws had been instrumental in one of the most important revolutions in the history of human thought, so would Planck’s discovery, that the energies of his “oscillators” must be quantised in order to explain blackbody radiation, spark another revolution that would forever change the way we view the world.

Five years later, Planck’s result led Einstein to explain the photoelectric effect through his proposal that, in addition to its electromagnetic wave nature, light also acts as the quantised packets of energy he called photons. Later still, it was this concept of energy quantisation that led Niels Bohr to his atomic model, which finally explained the emission and absorption spectra and completed the picture that had begun to be revealed a century earlier by Fraunhofer.

The word “quantum” comes from the Latin word meaning “how much”. The science that incorporates discrete quantities in describing the phenomena of the microscopic world—the science that emerged from Planck’s explanation of the blackbody spectrum—is called quantum physics or quantum mechanics. Let us now return to the picture of atoms, with their positively charged nuclei and negatively charged electrons, and see how Bohr developed this theory to explain the phenomenon of spectral lines.

A Little More Quantum Physics: Explaining Spectral Lines via Atomic Orbitals

Electrical charges and forces had been a subject of physical experimentation and investigation since the early eighteenth century. However, it was not until the end of the nineteenth century that the idea of an electron, as an elementary quantum of electrical charge, began to emerge. The electron was finally identified as a particle by J. J. Thomson in 1897. Ernest Rutherford’s discovery of the atomic nucleus in 1911 then helped to largely establish the atomic picture of a positively charged nucleus surrounded by individual electrons.

Now, already due to Maxwell’s work on the electromagnetic theory these charged particles were understood to influence one another through an electric field that surrounds each of them much like the gravitational field that surrounds all massive objects. In fact, it was partly the discovery of the electric field that prompted Einstein to develop his general theory of relativity (Einstein’s theory was discussed at the end of Module 3). The physical equation describing the force that one charged particle exerts on another, called the Coulomb force law, is in fact mathematically equivalent to the description of gravitational force given by Newton’s universal law of gravitation.

This equivalence between the forms of the mathematical equations describing electrical and gravitational forces implies that we can use our intuition about gravity to understand the force that binds electrons to the nucleus. That intuition, plus a little more quantum physics, is all we really need to be able to describe the way electrons “orbit” within an atom, along with the way they emit and absorb photons.

The force that binds an electron to a nucleus works just like gravity: it is an inverse-square law, which means that as an electron gets closer to the nucleus the force pulling it towards the centre increases exponentially. Similarly, as the electron moves out, the inward force exponentially decreases. Therefore, an electron orbiting closer to the nucleus needs a greater push if it is to move away from the nucleus than an electron that is already someplace further out. The energy needed to remove an electron completely from the nucleus is known as its binding energy. Therefore, Einstein’s 1905 explanation of the photoelectric effect proposed that in order for incident light to liberate an electron from an atom, the energy of a photon,

E = hν,

would have to be greater than the electron’s binding energy.

Now, rather than being stripped away from an atom, you might wonder whether an electron can ever fall into the nucleus, given that electrons are attracted to nuclei much like any mass is attracted to another. Actually, it turns out that the only time an electron ever enters the nucleus is when a star implodes during a supernova. In that case, the pressure of an entire star falling in on the atoms in its core is enough to drive electrons into the nuclei. When this happens, the electron and proton interact to produce a neutron plus a high energy neutrino. The energy of all the neutrinos released from the core of a collapsing star forces all the imploding matter to explode outwards, and what’s left behind is an expanding shell of gas with a neutron star at its centre.

The reason for mentioning what happens at the heart of a supernova is to illustrate the extreme physical situation that is required to cause an electron to “fall into” the nucleus of an atom. If an electron did orbit the nucleus of an atom much like planets orbit the Sun, there would be little reason that it couldn’t just fall in.

In fact, the situation was even worse because classical electromagnetic theory predicts that an orbiting charge should emit electromagnetic radiation—i.e. light—thereby losing energy. For this reason, an electron in a planetary-like orbit around a nucleus should actually spiral in. A good estimate for the amount of time this should take is around 16 picoseconds (i.e. one-trillionth of a second).

The solution to this problem that Bohr proposed in 1913 is now called the Bohr model of the atom. It did not incorporate Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, which was not introduced into quantum mechanics until 1927, but described electrons as moving in classical, planetary-like orbits around the nucleus with two additional quantum-like properties:

- There are finitely many discrete orbits at which electrons can orbit an atom stably without radiating (he based this idea on Planck’s result for blackbody radiation); and

- Electrons can jump from one orbit to another by emitting or absorbing a photon—a quantum of energy—whose energy is exactly equal to the energy difference between the two electron orbitals.

Bohr’s model was able to accurately predict the spectrum of a hydrogen atom (see Figure 5-11), but because it was not fully quantum-mechanical it did require subsequent modifications that are not important for our present purposes. (If you are interested in further reading, the Wikipedia page History of quantum mechanics provides a concise overview and an excellent further reading list). What is relevant for you to know is that the structure of every atom and every molecule—the number of protons, neutrons, and electrons it contains, and their geometrical arrangement—determines its own unique set of energy orbitals. Those orbitals show themselves to us in absorption and emission spectra as the electrons in those atoms and molecules interact with light.

Our main goal in exploring the history of these discoveries was that we needed to explain why light happens to have the different features it has; i.e. to explain how the characteristic glow of every object with a temperature above absolute zero, as well as the absorption and emission of light with specific frequencies, are due to the structures of atoms. Surprisingly, despite being continuous, we know that blackbody spectra can only have the observed shapes in observed intensity that they do because they are composed of atoms whose electrons exist in discrete energy orbitals. In contrast, the connection between discrete emission or absorption lines and discrete energy orbitals is far more obvious. Due to the Coulomb force pulling electrons towards the nucleus, they will inevitably tend to fall into the lowest possible orbit—but Bohr’s model tells us that this can only occur as a quantum leap to a lower orbital, with a photon of equal energy emitted in the process. One of the strangest features of the Bohr model is its other implication, that a photon simply will not interact with an electron if its energy is anything other than the difference between the electron’s current orbital and a higher one.

These are the basic quantum-mechanical results that allow us to look at an object’s spectrum and determine its physical properties. In the next section, we’ll explore some of the ways that astronomers are able to exploit this knowledge.