Having discussed the basic principles regarding the nature of light and the ways in which telescopes are used to collect light, it is important to make note of the environmental factors that affect astronomy. Telescopes are designed to gather light and focus it on a detector (such as your eye or a camera). However, they can only do so if they are located someplace where light at a specified wavelength is capable of being detected.

At most wavelengths, the best place to put any observatory is in space, where there is no atmosphere for light to interact with, no weather to keep astronomers from being able to make their observations, and no background noise from city light pollution. Furthermore, the scatter of sunlight that brightens the sky every day on Earth and limits astronomy to a night time activity, is not a problem in outer space.

In fact, as we learned earlier in this module, Earth’s atmosphere is opaque to most of the electromagnetic spectrum, so terrestrial astronomy can only possibly be carried out at optical, near infrared, and radio wavelengths. If we want to observe the universe at any other wavelength, we have no choice but to put telescopes in space (such as the Chandra X-ray Telescope).

Space telescopes are, however, extremely costly to place in orbit and to maintain, and they are far more challenging to operate, especially if we want to build very large ones with greater light-gathering and resolving powers. You may have noticed that the primary mirrors of the Hubble Space Telescope and the planned James Webb Space telescope in the bottom left-hand corner of Figure 4-8 are dwarfed by those of the largest telescopes that have been built on Earth. The reason for this disparity is feasibility (both practical and financial).

The practical benefits of building and operating telescopes on Earth mean that astronomers will continue to build observatories on the ground. In particular, radio telescopes will never be put in space because

- the Earth’s atmosphere, even when cloudy, is completely transparent to radio waves,

- radio sunlight is not scattered by Earth’s atmosphere, so radio sources from astronomical objects are observable day and night, and

- since resolving power is worse at long wavelengths, radio signals require enormous diameters in order to be resolved.

Despite the fact that we can see visible and infrared light that comes through Earth’s atmosphere, there are a number of factors affecting the quality of observations at these wavelengths that astronomers aim to mitigate. The question is, where is the best place to put a ground-based optical or infrared observatory?

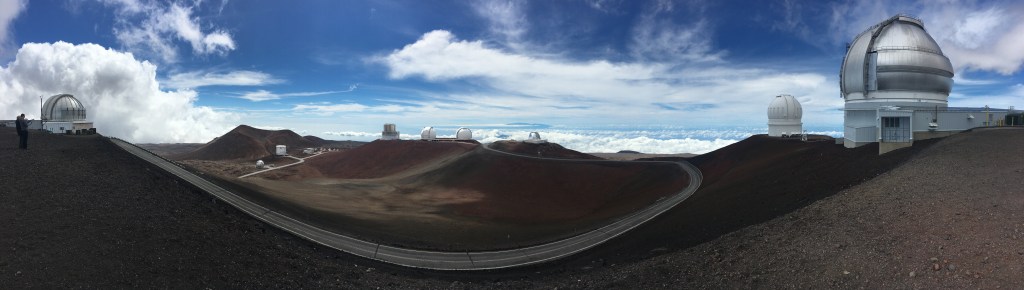

The best place to put an observatory is one where the weather is calm, where little precipitation or even cloud cover occurs, which is at a high altitude, and is far from city lights. On top of that, if the temperature is warm year-round and the location is near an airport so that astronomers can fly there from around the world, it is really ideal. For all these reasons, the two locations with the vast majority of the world’s largest telescopes are Hawaii and Chile (see Figure 4-10).

Placing telescopes on the tops of mountains such as Mauna Kea in Hawaii, at an altitude of 4205 m, means that they are above much of the clouds and weather that would otherwise limit the number of observing nights. Additionally, being so high up means that there is far less atmospheric disturbance, which can drastically reduce a telescope’s resolution. And finally, since Hawaii is an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean with controlled light pollution, there is very little background noise to affect observations.