Given the description of light as electromagnetic radiation with the properties of wavelength, frequency, and energy previously discussed in this module, you might be wondering about the possible ranges of each of those properties. For instance, can light be infinitely energetic, with infinite frequency and zero wavelength? Can a light wave have zero energy or frequency, and infinite wavelength? It turns out that these are the theoretical limits. Nothing actually has infinite energy, but the energies of light rays do get extremely high. Likewise, long wave electromagnetic radiation exists with wavelength on the order of a kilometre, but light that has no energy at all is actually nothing.

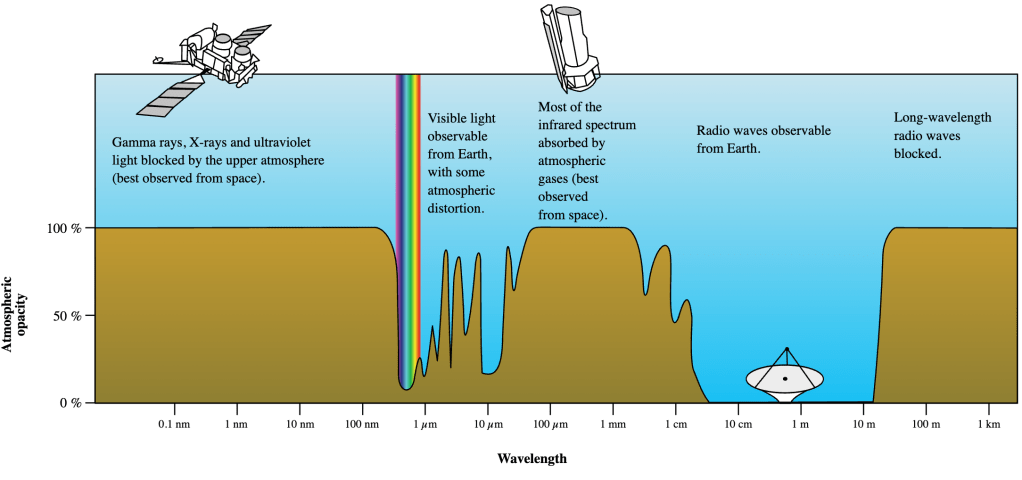

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of all possible wavelengths/frequencies/energies of electromagnetic radiation. You are most familiar with the spectrum of visible light, which ranges from red to violet—the colours of the rainbow. The wavelengths of visible light range from 700 nm (red) to 400 nm (violet), making up only a tiny window of the whole electromagnetic spectrum (see Figure 4-2). Note that 1 nm = 10–9 m (one nanometre is one billionth of a metre).

Just as we can sense the differences in the wavelengths of sound when we hear it, so our eyes sense the different wavelengths of light that we see. Similarly, just as our ears are not able to detect sound when the pitch is too high or too low, electromagnetic radiation is invisible to us when its wavelength falls outside the very narrow range of the visible spectrum. However, simply because our eyes are insensitive to them does not mean that other forms of electromagnetic radiation are particularly rare.

If you look through the names of the various ranges in the electromagnetic spectrum in Figure 4-2, you’ll likely find that you are familiar with most, if not all of them. Most people are aware of the harmful effects of high doses of ultraviolet light, X-rays and gamma-rays. These are shorter wavelength-higher energy forms of electromagnetic radiation which can cause cancer in humans who receive too much exposure to them. But practical uses exist as well. When we shine X-rays through a human body they do not pass through bone as readily as tissue, and as a result doctors are able to take pictures of our bones to look for fractures by exposing light that passes through a person’s body to X-ray sensitive film.

Similarly, you are probably familiar with longer wavelength forms of electromagnetic radiation such as infrared radiation, which is emitted by warm surfaces like the bodies of animals, and is visible through infrared-sensitive goggles. At even longer wavelengths we find microwaves, which are e.g. used to heat up food in a microwave oven, and radio waves, which are used around the world to transmit signals from devices like radio towers and cell phones.

Learning highlight

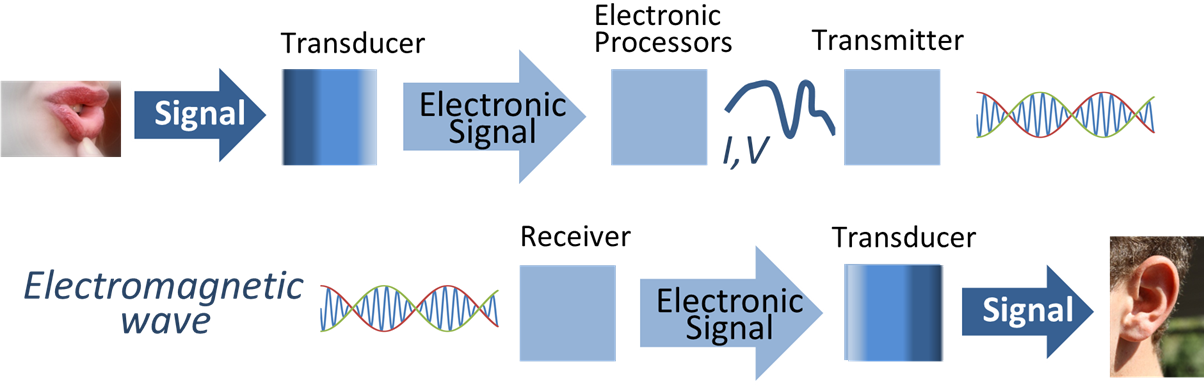

Have you ever wondered why you don’t hear the radio all the time? Or why you don’t hear people’s cell phone conversations as you walk down the street? It’s because radio signals are not sent as sound waves but as information that is encoded in electromagnetic radiation. See Figure 4-3 for an infographic that explains how radio works.

Electromagnetic radiation is all around us. Furthermore, depending on the wavelength of an electromagnetic signal, it may have a more or less difficult time passing through solid objects. Radio waves easily pass through walls, and X-rays (as well as radio waves) easily pass through skin tissue. If you’ve ever held a flashlight up to your hand in the dark, you’ll know that some visible light can also pass through thin layers of skin. As we’ll see in Module 5, the difference between electromagnetic radiation being absorbed and re-emitted by a material, rather than simply passing right through it, depends on the material itself and on the wavelength of radiation.

So: if light is just a form of electromagnetic radiation, and the electromagnetic spectrum spans invisible signals from gamma rays to radio waves, what is so special about visible light that makes us able to see it? The answer is that our eyes have adapted so that they are sensitive to the most intense sunlight coming through our atmosphere. As we’ll see in Module 5, visible light also comes from the part of the Sun’s spectrum where it emits light most intensely. Additionally, it turns out that the Earth’s atmosphere transmits visible light more readily than it does any other form except radio waves (see Figure 4-4). Since the Sun is a relatively weak source of radio waves, visible light is the most intense form of electromagnetic radiation naturally found on Earth. Our eyes therefore simply adapted so that we are able to see the world as brightly as possible.