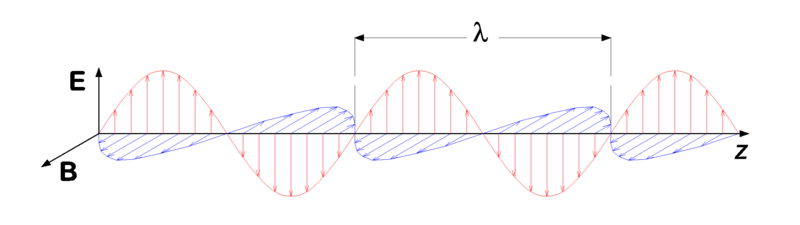

Earlier in this module, when I noted that billions of neutrinos pass through the Earth every second simply because it is empty space and neutrinos are electrically neutral (so they don’t interact with electrons and protons), you might have wondered about light and why it doesn’t pass right through the Earth. The reason why light doesn’t go through solid objects is that it actually isn’t electrically neutral. Light is electromagnetic radiation—a combination of perpendicular, oscillating electric and magnetic fields that radiate away from some source (see Figure 4-1).

In Module 3, you learned that Einstein’s general relativity describes the gravitational field as a curvature of space around a massive object. The gravitational fields surrounding two massive objects interact with each other and tell them how to move. Similarly, electric and magnetic fields surround electrically charged particles that are in motion, and the presence of an external electric or a magnetic field will influence the motion of a charged particle.

The great nineteenth century physicist, James Clerk Maxwell, was the first to recognise that electricity and magnetism are really two aspects of the same phenomenon, called electromagnetism. In addition, Maxwell realised that light is an oscillating electric and magnetic field—electromagnetic radiation. Light therefore interacts with electrically charged particles like electrons and protons, which are surrounded by electromagnetic fields.

One of the most peculiar aspects of light is that it can behave either as a wave or as a stream of particles. In the former view, a ray of light is pictured as in Figure 4-1, as a wave that oscillates with a given frequency (denoted by the Greek letter ν, pronounced “nu”). That frequency depends on both the speed of light (c) and the distance between peaks of the wave, called the wavelength (λ, another Greek letter which is pronounced “lambda”), as

ν = c/λ.

Note that if c is measured in units of meters per second, and if λ is measured in units of meters, this equation indicates that ν must be measured as “per second”. Another name for this unit is hertz, after the German physicist Heinrich Hertz who was the first to find conclusive evidence of the existence of Maxwell’s theorised electromagnetic waves.

In addition to having wavelike properties, electromagnetic radiation of low enough intensity manifests as individual particles, called photons. While various concepts of particles of light date back to ancient times, the modern idea of a photon was proposed by Einstein in 1905, in order to explain a peculiar phenomenon.

Prior to Einstein’s 1905 proposal, it had been known that electrons can become dislodged from atoms when light shines on them, but the rate at which this tends to occur does not depend on either the intensity or the wavelength of light in the way one would expect from the perspective of classical electromagnetic wave theory. For instance, when light of sufficiently low intensity first shines on a material, classical theory suggests that there should be a time lag before electrons start to become dislodged. However, it was observed that no matter how low the intensity, electrons instantly begin to be dislodged at a rate proportional to the intensity of the light source. Furthermore, it was found that light with long enough wavelength will never dislodge electrons, no matter how intense the source may be.

In order to explain these observations, Einstein proposed that light could be described as discrete wave packets, called photons, and that the intensity of light with a given wavelength is equal to the number of photons of that wavelength that are emitted by a source. Furthermore, he proposed that the energy (E) of an individual photon should be proportional to its frequency (therefore, inversely proportional to wavelength):

E ∝ ν = c/λ.

This way, as long as the energy of an individual photon is sufficient to dislodge an electron, he suggested that is precisely what would happen—even in the case of a single photon being shone on the material. He called the phenomenon the photoelectric effect.

Learning Activity

A useful analogy is to think of a 1 kg weight sitting on the top of a table. You could hit the weight with paper airplanes with unlimited intensity (e.g. ten per second) and it would never budge. However, hitting the weight just once with a basketball—or anything else above a certain threshold mass/speed—would be enough to knock it off the table.

Einstein’s proposal accurately predicted both the threshold nature of the wavelength (or frequency) of light required to dislodge electrons from a material, and the fact that electrons will be dislodged provided this threshold is met, regardless of the intensity of the light source. In 1921, after the photoelectric effect had been sufficiently confirmed by experiment, Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics “for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect” (Nobelprize.org).

As we shall see further on in this module, the modern method of imaging astronomical objects is a particularly important application of the photoelectric effect. However, before we discuss making these records of the electromagnetic radiation that comes through a telescope, we will first explore how telescopes work. And before we do that, we must first complete our description of electromagnetic radiation—and its many forms beyond merely the visible light that we can see with human eyes.