Now that you’ve explored what light is and how it transmits signals across space which inform us about distant objects (such as computer monitors, stars, and planets), it is time to examine what optical telescopes do. Most of this, you will actually do in Observing Lab 1, where you’ll see for yourself how a telescope gathers light, and how different eyepieces can be used to view that light at different magnifications with different fields of view. This section of the module will provide an overview of how that all works so you have a better idea of what you are doing as you follow through the steps in the lab.

For now, we’ll specifically concentrate on describing the way optical telescopes enable us to observe enhanced visible light coming from distant objects. However, as you learned in the last section, visible light accounts for only a small percentage of all the electromagnetic radiation that is potentially observable, and astronomers need to utilise every bit of information they can in order to learn all we can know about the universe. The principles of astronomy at wavelengths other than the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum are essentially the same; therefore, when we have completed our discussion of the basics of optical astronomy, we can easily extend what we’ve learned to describe how astronomy works in other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum as well.

Light-gathering power

First and foremost, telescopes are light buckets. You can—and should—think of telescopes with different diameter openings as you would a bucket sitting outside in a rainstorm. The larger the bucket’s opening, the larger the volume of rain you’ll catch. Similarly, the larger the telescope’s opening, the more light you’ll catch.

If you allow your eye to become well adapted to the dark on a clear, Moonless night outside the city, your pupil will dilate to a maximum of about 7 mm in diameter. At this diameter, the size of the area that will gather light and focus it on your retina is π (7 mm/2)2 = 38.5 mm2.

If you then use a telescope to gather light and focus it on your eye, then the area you are using to capture that light is the area of the telescope’s opening. If you were to hook an eyepiece up to the Hubble Space Telescope, for instance, which uses a 2.4 m mirror to capture light, the light-gathering area would be increased to 4.52 m2 = 4,520,000 mm2.

Since it’s the light-gathering area that determines how much light an instrument (e.g., a telescope or an eye) gathers, this means that the Hubble Space Telescope should gather 4,520,000/38.5 = 118,000 times more light. Note that the only value that changes when calculating these light-gathering areas is the diameter of the telescope, which is squared. In general, the ratio of the light-gathering power of instrument A (LGPA) to (LGPB) is given by the ratio of the squares of the diameters DA and DB of their openings, i.e.

Light focusing: refracting and reflecting telescopes

The size of a telescope’s opening serves another important purpose: it determines how fine the resolution of the image will be. But before moving on to discuss how that works, I want to clarify two points that I glossed over in discussing light-gathering power.

The first is my use of the word “opening”. Technically, it isn’t really the opening itself that collects the light so that objects appear brighter. If you took any tube and held it up to your eye, the things you would see wouldn’t be any brighter. The reason is that all the light that enters the tube doesn’t magically get directed toward your pupil; it gets absorbed and reemitted by the walls of the tube, and much of it hits your face around your eye. In addition to a large opening, you also need a series of lenses, or a combination of lenses and mirrors, which redirect all that light so that it enters your eye.

The manner in which light is redirected through a lens is called refraction. When light passes from one medium into another, such as from air into glass, it gets refracted by an angle that depends on the properties of the two materials and on the wavelength of the light; red light is refracted a smaller angle than blue light. When light passes through a lens, it is refracted so that all the light of a particular colour comes together at a single point, called the focus. Figure 4-5 shows what happens to white light, composed of all colours, when it passes through a lens. Notice that the focal points of different colours of light are different.

Now, from Figure 4-5 you should start to see how we can use lenses to gather light from a larger area than our pupils. However, this lens clearly does not do a very good job of collecting light in any way that a person could see a clearer, brighter image. There are actually two problems with using a lens like the one in Figure 4-5 to gather light. First of all, none of the colours come together at the same focal point. In other words, the focal lengths—the distance between the centre of the lens and its focus—of different coloured light are different. This is called chromatic aberration (as Figrue 4-5 suggests), and it turns out that it can be fixed by adding a second lens to the first which causes all visible light to come to the same focus; i.e. to have the same focal length. When you build your Galileoscope, you’ll see that its primary lens does in fact have two lenses cemented together for this very purpose. The second problem with using just one lens like the one in Figure 4-5 to collect light is that if you look at light that has been bent this way and that while it passes through a lens, the image you see is going to look like it’s been bent this way and that! In order to preserve the image that is incident upon the telescope’s primary lens, we therefore require a second lens—the eyepiece lens—to straighten everything back out. Figure 4-6 shows how a refracting telescope brings all of this together, gathering a large amount of light into a small image in which the shape is preserved.

Before moving on from this discussion of how a refracting telescope works, to describe how we can use a mirror instead to do the job of the primary lens, there are two important things to note in Figure 4-6. The first is that the focus of the primary lens and the focus of the eyepiece lens are at the same point. If they weren’t, the image would appear out of focus. In order to focus a telescope, all you need to do is move the eyepiece forwards or backwards to the position that lines its focus up with that of the primary lens. The second important thing you should notice in Figure 4-6 is that the image must be upside down. To see this, follow the line of light from the top of the primary lens down to the bottom of the image that leaves the telescope’s eyepiece. Since the top of the incident image ends up at the bottom of the image that leaves the telescope, and the bottom of the insident image ends up at the top, the image must appear inverted!

Learning Highlight

Did you know that the lens in your eye inverts the image of everything you see much like the lens of a refracting telescope, but that your brain processes what you see so that the world does in fact appear right-side up?

Now, the principles behind using a mirror to collect light within a telescope are essentially the same as with a lens, except that the telescope uses light reflection rather than refraction. The most common set-up for a reflecting telescope has a primary mirror at the base of the tube, which catches light and reflects it back to a smaller, secondary mirror at the top-end of the tube, which then reflects the light down through a small hole in the primary mirror (where it gets straightened out with a lens); see Figure 4-7.

There are advantages and disadvantages of both reflecting and refracting telescopes. The main disadvantages of refracting telescopes are:

- large lenses are more difficult to manufacture than large mirrors because they must be much thicker and can have no imperfections,

- while glass is quite rigid, lenses do tend to distort over time, particularly when they are large, and

- lensed images suffer from chromatic aberration, which cannot be corrected exactly over all wavelengths.

The main disadvantage of reflecting telescopes, on the other hand, is that the secondary mirror blocks a portion of the incoming light. If your telescope is, say, only 50 mm in diameter, then even a 10 mm secondary mirror blocks a significant portion of the incoming light. However, this is far less of an issue with very large-diameter telescopes, where the area of the secondary mirror can get quite small in relation to the area of the primary mirror. When it comes to building large telescopes, this minor issue is far outweighed by all the advantages of constructing large mirrors instead of large lenses.

The most important advantage that reflecting telescopes have over refracting telescopes is that they can be made so much bigger. Due to the fact that the primary lens of a refracting telescope must be free of imperfections in order to be of any use, the largest refracting telescope ever built for scientific research is the 102-cm Yerkes Observatory telescope in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, which has a 19.4 m focal length. In contrast, reflecting telescope mirrors have been built with ten times the diameter, and more recently telescopes have been built by piecing together hexagonal mirrors for even larger designs (see Figure 4-8). Today, all large professional telescopes are built with mirrors rather than lenses, while both remain common in small amateur telescope designs.

Resolving power and magnifying power

So far, we have explored the concept of a telescope as a big light bucked that gathers as much information as possible from space, and we’ve examined how telescopes focus that light into enhanced images. The other main functions of a telescope are its resolving power and its magnifying power.

Even if you’ve never looked through a telescope before, you’re likely aware that a telescope does more than just make objects brighter. If that were all it did, we could not expect to see mountains and craters on the Moon, or the rings of Saturn. Those objects are already sufficiently bright, but their details are so fine—the distances cover such small angles—that they have to be better resolved and magnified in order to become visible.

In a way, resolution and magnification go hand-in-hand: no matter how well an image is resolved, if we do not have the power to magnify it we cannot see its fine details; on the other hand, you can blow up a low resolution image all you want and you’ll never be able to pick up unresolved details. However, the resolving power and the magnifying power of a telescope are determined quite differently.

The theoretical resolution of any mirror or lens, including the lens in your eye, is limited by the fact that light is a wave, so parallel beams of light tend to interact with each other if they are close together. In order for you to resolve two distinct objects with your eye, the angular distance between those two objects must be great enough that the electromagnetic waves coming from each of them is able to enter your eye without interacting with the electromagnetic waves from the other. The wider the lens in your eye, the greater the chance that you can resolve the two distinct objects. Similarly, the wider the diameter of a telescope’s primary mirror or lens, the greater its resolution will be.

The theoretical resolution limit of a telescope is similar to the telescope’s light-gathering power in that it depends on the primary mirror or lens only; however, there are important differences. First of all, a telescope’s resolving power is proportional to the diameter of the lens or mirror, whereas its light-gathering power is proportional to the area, and therefore the square of the diameter. Secondly, resolving power also depends on the wavelength of light that is being observed: the longer the wavelength, the worse the resolution will be.

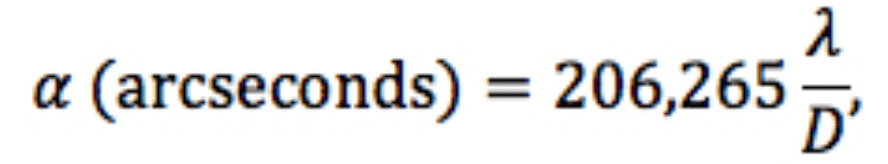

A telescope’s resolving power is given in terms of the smallest angular width that can be resolved. Therefore, as resolving power improves, its value decreases. When observing light with wavelength λ, a telescope whose primary mirror (or lens) diameter is D has a theoretical resolving power (in units of arcseconds) given by

where λ and D have the same units.

A common misconception about telescopes is that their primary purpose is to magnify objects. However, according to the discussion so far, you should begin to appreciate that magnification is the least important of the three powers. If a telescope did not resolve fine details in dim objects, but only magnified them, its only purpose would be to make small dim blobs appear larger. That’s not very impressive, especially considering the fact that with modern technology any image you might take through a telescope can be easily magnified on a computer screen. And for this very reason—i.e. the fact that magnification is so easily achieved—you might (correctly) suspect that magnifying power is not an intrinsic property of a telescope’s objective mirror or lens alone.

A telescope’s magnifying power, M, is given by the ratio of the focal length of the primary mirror or lens, Fp, to the focal length of the eyepiece, Fe, i.e.