Although pulsar planets are exotic, rare objects that were interesting mainly because they were the first type of planet scientists ever observed around another “star,” the discovery was unsatisfying in terms of our search for other habitable worlds and the question of whether life exists beyond Earth. Neutron stars emit intense radiation only from their magnetic poles and produce almost no steady heat. A planet orbiting a neutron star would have a temperature near absolute zero and would be completely inhospitable to life.

We believe that life requires a sustained energy source and therefore can only exist on a planet orbiting a star like our Sun, which maintains a nearly constant luminosity over billions of years through a steady rate of hydrogen fusion in its core. For this reason, astronomers were unsatisfied with the discovery of pulsar planets, and the search continued for the first planet orbiting a true, Sun-like star.

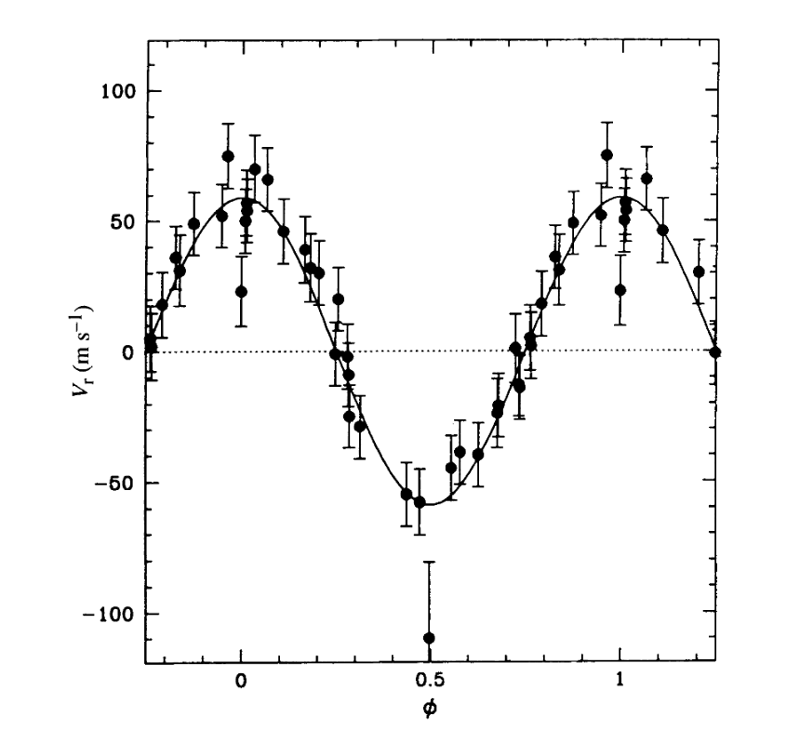

The wait was short. In 1995, Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz announced the discovery of a Jupiter-mass companion to a Sun-like star, 51 Pegasi. The detection came from Queloz’s PhD research, using the radial-velocity method to observe a periodic Doppler shift in the star’s light. Following the official extrasolar-planet naming convention, in which a lowercase Roman letter is added to the star’s name beginning with “b,” the planet was designated 51 Pegasi b. Similarly, Draugr, Poltergeist, and Phobetor are named PSR B1257+12 b, c, and d.

Source: M. Mayor & D. Queloz, Nature 378 (1995)

Like the pulsar planets discovered a few years earlier, 51 Pegasi b was detected through the apparent wobble of its parent star—by measuring the periodic Doppler shift in its spectrum (see Figure 11-3). But 51 Pegasi b’s very existence posed a profound challenge for planetary scientists. The planet, roughly half the mass of Jupiter, orbits its star once every 4.23 days at a distance of just 0.05 AU.

Based on observations of our own Solar System, astronomers had long assumed that Jupiter-like planets could form only at large distances from their stars. Nearer the star, high temperatures would prevent a planet from retaining the light gases needed to grow to Jupiter size, yielding instead a small, rocky world. For that reason, many scientists were initially sceptical of Mayor and Queloz’s claim. Yet follow-up observations quickly confirmed it—and since then, hundreds of hot Jupiters have been found orbiting close to their parent stars.

Today, the most widely accepted explanation is that hot Jupiters formed farther out and later migrated inward. The migration may have occurred gradually through gravitational interactions with the gas disk (disk migration) or later through gravitational encounters with other giant planets that produced highly eccentric orbits (high-eccentricity migration). Either way, the discovery of 51 Pegasi b forced astronomers to rethink planetary dynamics—just as the Nice model you studied in Module 10 reshaped our understanding of how the giant planets of our own Solar System moved into their present positions.

Mayor and Queloz’s discovery was a turning point. It not only revealed a new class of planet but also showed that such worlds could be detected with existing technology. The result opened the floodgates: astronomers around the world began dedicating telescope time to planet searches, setting the stage for the great survey missions that followed.

In 2019, Mayor and Queloz were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery. Their work transformed planetary science into a rapidly expanding field that now boasts more than 5,600 confirmed exoplanets—ranging from giant hot worlds to Earth-sized planets orbiting in their stars’ habitable zones.

The following video documents the early history of exoplanet discovery. It traces the breakthroughs that began with Mayor and Queloz’s detection of 51 Pegasi b and follows the cascade of discoveries that led to NASA’s Kepler mission—the most successful planet-finding mission to date, which identified nearly 5,000 planetary candidates and confirmed more than 2,700 planets, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of how common worlds like our own are.

Much of the story in the video centres on Bill Borucki, the NASA engineer whose persistence made the Kepler mission possible. As early as the 1980s, Borucki began developing sensitive photometers to detect the tiny dips in starlight that would occur when a planet passed—or transited—in front of its star. His proposal was repeatedly rejected before finally being approved in 2001, leading to Kepler’s 2009 launch. The mission’s success not only confirmed thousands of planets but also demonstrated that planetary systems are the rule, not the exception. Borucki’s work laid the foundation for today’s generation of planet-hunting observatories, including TESS, PLATO, and the James Webb Space Telescope, which continue to refine our understanding of distant worlds.