It’s impossible to capture the significance of Einstein’s relativity in a single example. The impact of Einstein’s theories spans from the everyday to the cosmic.

GPS navigation only works because both special and general relativistic corrections are applied: without them, positions would drift by 10 kilometres per day, compounding rapidly while the entire system would be almost immediately useless.

Modern atomic clocks are so precise they can detect time slowing from raising a clock just a few centimetres in Earth’s gravitational field — a precision now used in Earth science and geodesy.

If you’ve ever seen an image of a distant galaxy distorted into an arc or a ring, you’ve seen general relativity in action: gravitational lensing, the warping of light’s path by massive galaxies and clusters, for which no alternative explanation exists.

And in the most stunning confirmation of all, relativity’s prediction that moving masses should ripple through space-time has enabled us to detect signals from colliding black holes and neutron stars with a precision reaching 21 decimal places.

But did the man who formalised this theory and derived its most astonishing and provocative consequences — which impact our lives every day, and have been subjected to the most sophisticated and accurate experimental tests in all of physics — fail to fundamentally understand its true meaning?

Even asking the question must surely raise eyebrows. I suspect they’ll raise a little more, however, when I say in all sincerity that I’m convinced he did.

The basics of relativity

You’ve likely passed a ball with someone in your life — a baseball, football (whether that’s the sport that uses hands or feet), dodgeball — whatever. Imagine you and a friend are playing catch with an American football. You’re both standing still, and you throw the ball with the same speed every time, back and forth, so it’s always in the air for the same amount of time. Let’s call this scenario A.

Now, imagine that at the same time you throw the ball your friend starts walking towards you at a constant speed. Clearly, they’ll catch it sooner than they had been, as they’ll intercept it somewhere along the path the ball had previously been travelling, before it gets to the place they were standing when you threw it. Let’s call this scenario B.

Now, imagine that they’re back to the original spot, and this time when you throw the ball both you and your friend start walking so you maintain constant separation while the ball is in the air. You’re walking backwards while they’re walking forwards, the ball flies their way and is caught at the same place they caught it in scenario B, but this time there’s constant separation between you two. We’ll call this scenario C.

The essence of relativity — both where the theory gets its name and how we interpret it as a description of physical reality — boils down to how you answer two simple questions:

- In scenario C, does the ball take the same amount of time to reach your friend that it did in scenario A, or does it take the same amount of time as it did in scenario B?

- If the separation between you and your friend remains perfectly constant in scenario C, and you’re not being accelerated, can you really be said to be moving at all?

Most of us would say the ball takes the same time to reach your friend in scenarios B and C, and that it doesn’t matter whether or not you move after you’ve thrown the ball. And most of us would say that in scenario C you and your friend are both moving while the ball is flying through the air in the opposite direction.

But Einstein’s take on the fundamental meaning of relativity was that we should instead answer “No” to the second question, and therefore to say that the amount of time it takes the ball to reach your friend in scenario C is actually the same as in A, not B.

What about relativistic corrections?

With reference to the thought experiment above, we must clarify two things:

- The three scenarios I’ve outlined aren’t concerned with sending photons back and forth, but a ball instead, which is thrown much more slowly than the speed of light; and,

- Technically, Einstein would say the ball takes slightly less time to reach your friend in scenario C than it does in scenario A, due to special-relativistic time dilation, length contraction, and velocity addition.

However, neither of these points is actually significant in our discussion here: we need not be concerned about developing relativistic intuition through a thought experiment that uses a football instead of photons since the relativistic phenomena we’re concerned with here do not specifically depend on photons or the light-postulate; and, in this particular scenario the special-relativistic effects according to which the ball’s flight time in scenario C is different from the flight time in scenario A are vanishingly small and insignificant.

For these two reasons, we can effectively ignore the vanishingly small relativistic corrections to the distance between you and your friend in scenario C, the ball’s flight time, and the ball’s speed, and can consider direct implications for the meaning of the relativity of simultaneity that can be inferred intuitively through this thought experiment.

The essence of relativity

The local physics in all three scenarios is independent of what you define to be “at rest.”

You could, for example, define the Earth to be at rest in all three scenarios, and conclude that the ball takes longer to reach your friend in scenario A, while it takes the same amount of time to reach your friend in scenarios B and C.

Instead, you could define yourself to be at rest in all three scenarios. In that case, in scenario C as you and your friend move your feet it will be the Earth itself that rolls past under you like the belt on a treadmill. In that case, it’s clear that the ball will take the same in scenario C as it does in scenario A to reach your friend — as that time interval must be independent of whether the Earth is moving or not, and should depend only on the relative distance between you two and the speed of the ball, which are both the same in scenarios A and C. In this case, you would also say the ball reaches your friend after a shorter time interval in scenario B since they walk towards you while the ball is in the air and intercept it after it travelled a shorter distance.

From the standpoint of local relativity and its experimental tests, both sets of descriptions are equally valid. You may take the Earth to be at rest in all three scenarios, you may take yourself to be at rest in all three scenarios — or you can arbitrarily define any other state of rest you prefer, and it can even be a different one in all three scenarios.

For this reason, motion is commonly taken to be purely relative, dependent on the state of rest one assumes in formulating a physical description. In essence, we say there is no objective truth of the matter when it comes to definitions of “rest” and “space”; one’s arbitrarily chosen frame of reference defines both “space” and also “motion” through space from their perspective.

The ambiguity of now

In addition to definitions of space and motion through it being arbitrarily defined, it’s a simple matter to show that whether two events occur at the same time or not also depends on how one defines motion and space. To see this, imagine that in scenarios A, B, and C, you add a second friend, on the opposite side of you, who maintains a fixed distance from your other friend in all three scenarios, who is the same distance from you as your other friend at the moment you throw the ball. You also now have two footballs, which you’re able to throw simultaneously in the two opposite directions with exactly the same speed.

From the perspective in which the Earth is taken to be at rest, the balls arrive at your two friends as follows.

- In scenario A, all three of you are at rest with respect to each other and the Earth. The two balls travel the same distance at the same speed, so they arrive at your friends at the same time.

- In scenario B, at the moment you throw the balls your one friend moves towards you while the other moves away, so the ball is caught first by the friend who moves in your direction, then later by the friend who is walking away, since the distance of travel is shorter overall for the first friend and longer overall for the second friend.

- Finally, scenario C is essentially the same as scenario B, except you now walk in the same direction at the same speed as your friends after throwing the ball, maintaining constant relative distances. But since your motion after throwing the ball has no bearing on how far the balls travel or how long they take to arrive at your friends, you all conclude that the ball got to the first friend first and the second friend second.

But now, we switch perspective and describe all three scenarios as if you are always at rest, with all motion defined relative to you.

- Scenario A comes to the same result since you, your friends, and the Earth are all relatively motionless.

- In scenario B, you and the Earth are still at rest while your friends move towards or away from you. The first friend who walks towards you receives the ball before the friend who walks away from you.

- But now in scenario C, the situation is essentially reversed from the perspective in which the Earth was taken to be at rest. Now, after you throw the ball, you and your two friends start moving your feet, all three of you remaining in the same position while the Earth scrolls past underneath like a treadmill. Now, the two balls must take the same amount of time to reach your two friends, so they arrive at the same time.

This is, in essence, the phenomenon known as the “relativity of simultaneity.” It comes to mean that, according to relativity, not only are space and motion defined locally, within a given frame of reference, but simultaneity is as well.

Whether two distant events, such as when your two friends catch the two balls, happen “simultaneously” or not is understood, according to relativity theory, to be ambiguous — a matter of relative perspective and arbitrary definition.

A philosophical fork

Essentially, these results lead to a philosophical fork. On the one hand, we can infer from these results that motion, space, and now are all relative; that the definitions of each are ambiguous and there is no objective truth about whether two events happen “simultaneously” or not, or whether something can truly be said to be “moving” through “space.”

On the other hand, relativity is not actually inconsistent with there being a “true” state of rest, a true definition of “space,” and an objective definition of “simultaneity” and of “now” in reality. Relativity simply tells us that a valid description can be given from any relative reference frame. In this case, there would be a well-defined set of events happening right now, e.g., in the Andromeda galaxy. And the reality of this would not depend on whether you are running towards Andromeda, away from it, or sitting still.

Essentially, this fork really comes down to whether we should insist — together with Einstein — that the most objective description of scenario C is the one where you and your friends are described, from your perspective, as being at rest, with the two balls being caught simultaneously. When we insist that this is indeed the most objective interpretation for you to make from your perspective, and not that you and your two friends are actually walking along a fixed Earth, then we arrive at the standard conclusions, that motion, space, and simultaneity are purely relative.

But what if there actually is a true state of rest in our universe?

Cosmology’s absolute time

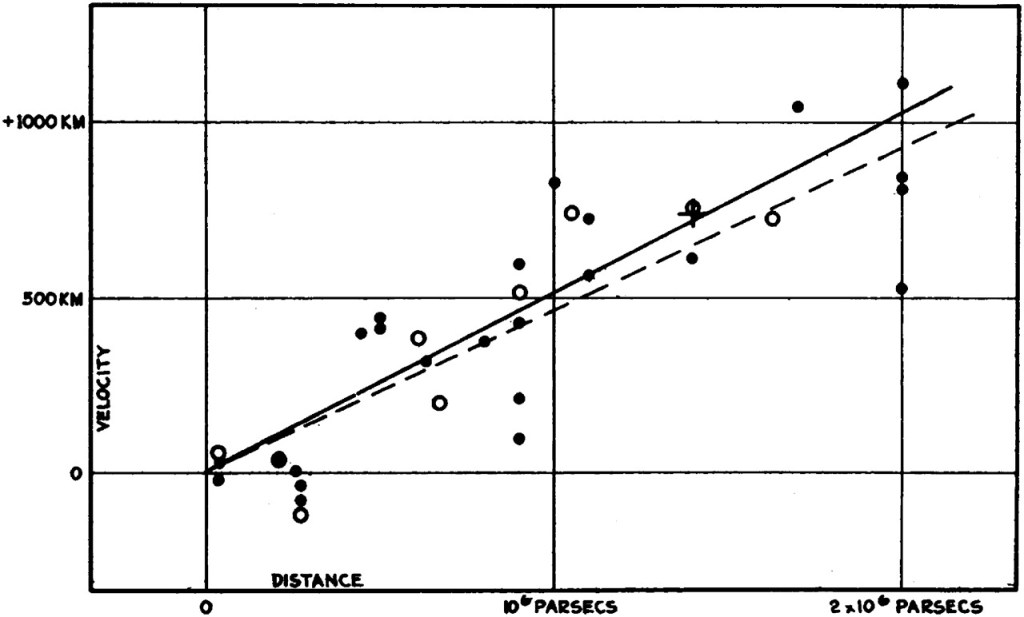

In 1929, Edwin Hubble discovered that there is a linear relationship between the distance to any galaxy and its redshift. Within a few years, cosmologists settled on an interpretation of Hubble’s Law that describes these redshifts not as Doppler shifts due to the speeds of galaxies. Under that interpretation, Hubble’s Law would then imply that we are at a special place in the universe from which all galaxies are fleeing, with the furthest ones moving the quickest.

Instead, cosmologists interpret Hubble’s Law as implying that our universe is a uniformly expanding three-dimensional space, somewhat like the two-dimensional surface of a balloon that’s being inflated, with dots to represent the galaxies.

In this scenario, all the galaxies do effectively flee from every point — and with speeds that increase in relation to how far they are from a given point. However, this effective motion is not what gives rise to their redshift, as it would if it were a Doppler shift. Within the expanding universe paradigm, the average motion of galaxies through space is assumed to be zero, and apart from very nearby galaxies the speeds are low enough than any corresponding Doppler shift is relatively small compared to the redshift due to expanding space.

In the standard model, the redshifts of galaxies that increase with increasing distance are described as a result of the continuous expansion of space along the path that light takes from distant galaxies to us. The redshift therefore does not depend on any intrinsic property of the emission source, but instead tells us about the expanding space that the light from each galaxy travels through.

The remarkable thing about Hubble’s Law is that the relationship is isotropic — the relationship between a galaxy’s distance and the amount of stretching that intervening space has undergone, leading to the cosmological redshift, is the same no matter which direction we look. Cosmologists in the 1930s therefore took this evidence to support a bold hypothesis: not only does the standard model describe space as expanding over time, but we assume space is — at the level of precision accessible through the redshift-distance relation — both perfectly uniform (appearing isotropic from every point in space) and uniformly expanding.

Initially, the idea that space is both uniform and uniformly expanding was assumed to be valid only on very large scales. This is important because the expansion of space is understood to depend on the energy densities of things like matter, radiation, and dark energy within the universe — and we can clearly see that our universe is rather lumpy, full of overdense galaxy clusters and huge underdense cosmic voids. Therefore, the observable universe is not expected to have been expanding perfectly uniformly.

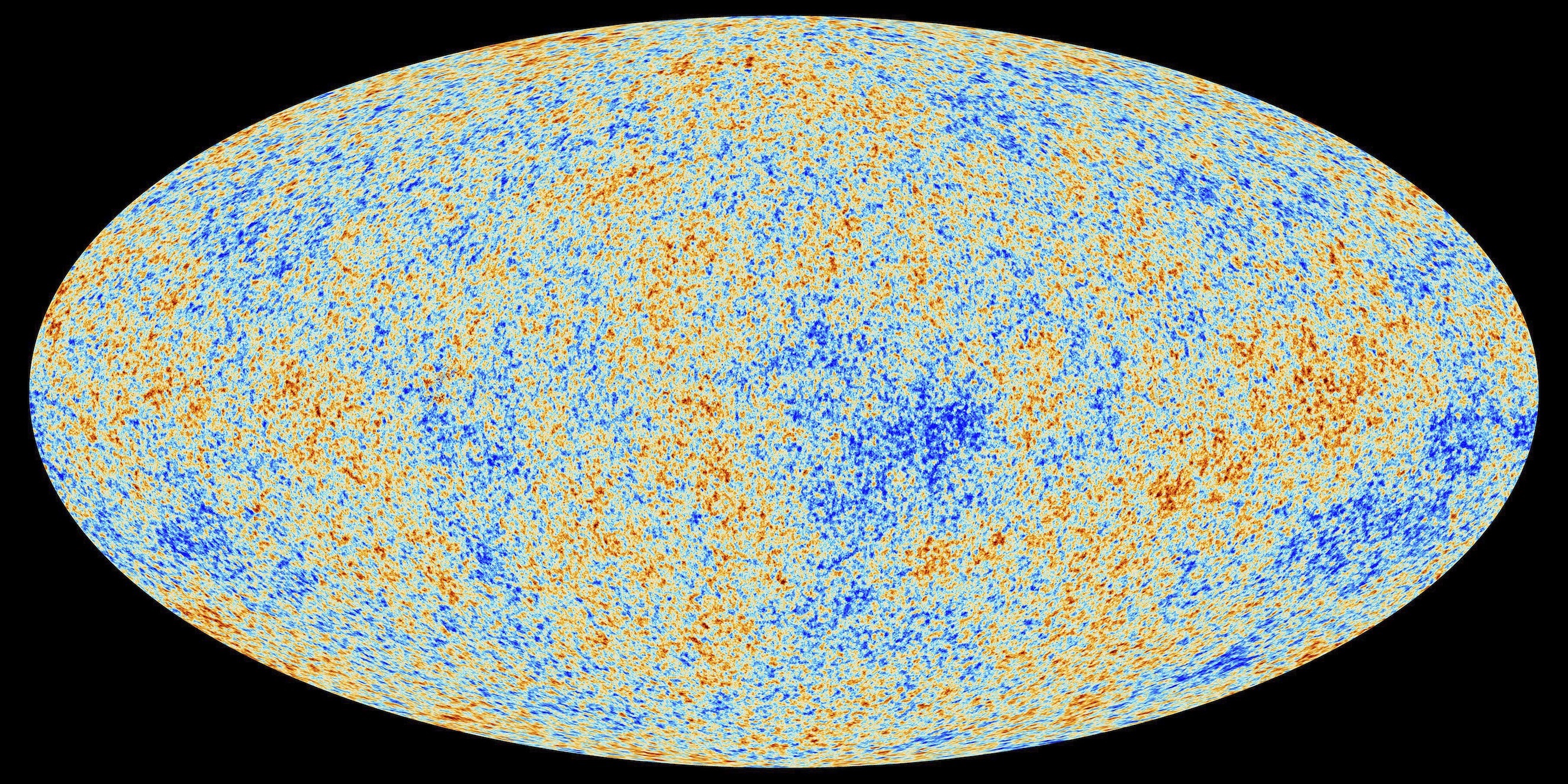

But gradually, over the course of the past century, we’ve found surprisingly clear evidence that the universe actually has been expanding precisely uniformly. The best evidence of this comes from the cosmic microwave background. CMB photons escaped from matter in the early universe, when the expansion of space had cooled temperatures to a few thousand Kelvin. At this point, the photons which had previously been interacting with matter became too cool, so they have been travelling through space ever since, becoming more and more redshifted as the universe continues to expand.

The uniformity of the CMB tells us many things. It tells us that the universe was highly uniform at the time the photons were emitted. And the uniformity of the CMB redshift tells us that the overall expansion of space along every line of sight has been precisely the same. According to the standard model, our lumpy universe actually should not have expanded as uniformly as the CMB data indicate — but the universe itself is not beholden to the models we use to describe it. And ultimately the data themselves show that the universe has expanded throughout the past 13.8 billion years with such uniform precision, that the anisotropy signature we do observe through precision measurements made with the Planck satellite is

- Only present at a level of 1 part in 100,000; and

- Even that is explained not by anisotropic expansion, but rather by anisotropies in the distribution of matter at the time the CMB was created, leading to small gravitational redshifts.

Actually, the fact that the small-scale anisotropy signature due to primordial anisotropies in the universe’s matter distribution was isotropically preserved through the expansion of space indicates that any possible anisotropy in the expansion of space itself must be less than 1 part in 100,000 in all directions.

Therefore, since Einstein’s initial development of his theories of relativity, we’ve found strong evidence that reality does consist of an objective “space” that continually expands, which defines an absolute state of rest and simultaneity. In fact, through measurements of the CMB dipole, we’ve found that our velocity through the universe is 369.82 ± 0.11 km/s toward the constellation Crater.

The universe has not only revealed that there is a true state of rest, but has let us measure our exact velocity through it.

Einstein’s philosophical insistence that motion and simultaneity are fundamentally relative does not survive the evidence. A century later, the universe has quietly revealed its secret: there really is a cosmic rest frame, and we are moving through it.

And this empirical fact fundamentally alters the basic meaning of relativity. Einstein’s equations remain flawless — but his preferred interpretation of the basic meaning of the theory must shift to align with the evidence.

Leave a comment