Imagine you’re on a train or a plane, gliding at constant speed. Four hundred years ago, Galileo Galilei clarified something remarkable about this situation—something that would forever change physics: in such an “inertial state,” everything inside the moving vehicle behaves exactly as it would if the vehicle were standing still.

Think about it. If you jump straight up in the aisle, the train doesn’t rush out from under you so that you land metres behind your seat. When the train accelerated earlier, so did you. The seatback, the floor, your own muscles—together they brought you up to speed. By the time you’re cruising smoothly, you share the train’s momentum. No further push is needed to keep you moving with it. You are in the same inertial state.

So, when you jump straight up, you come right back down where you started. Your momentum carries you through the air even when you aren’t touching the ground. Your connection to the ground when you are standing there is not the reason why you keep moving forward.

That’s obvious to us. We’ve all been on planes, trains, or cars moving steadily down a highway.

But without that experience, it isn’t obvious. For thousands of years people thought differently. They believed that if you leapt straight up from a runaway cart, the cart would dash ahead while you dropped straight down, landing behind it at precisely the point below where you jumped. And indeed, on a bumpy road with jostling horses and clattering wheels, forces do throw you about and it’s not easy to disentangle your forward momentum from the rest. And at slower speeds, you might subtly push yourself backwards, and among all the other jostling forces a slight backwards shove could go unnoticed. But in a perfectly smooth cruise, the effect is clear—and at high speeds it’s unmistakable—a subtlety hidden from ancient eyes.

You know this firsthand. Picture your last flight: a jet slicing smoothly through the air at 300 metres per second. If you jumped straight up in the aisle so you were off the cabin floor for a second, you wouldn’t be hurled 300 metres backwards. If Aristotelian physics had been true, you would have to be strapped down at all times in order to fly at such a speed, and you’d feel a constant force keeping you moving with the plane. If you did make that one-second hop, you’d crash hard into the back of the plane, and unless it had a 300-metre cabin you’d probably crash right through it since your body would be moving relatively at 300 metres per second upon impact.

But in reality, if you jumped straight up while cruising, you’d land straight back down on the very same spot. If you hopped two feet toward the front, you could just as easily hop two feet back and end up at the same place you started. If you stood mid-cabin with a baseball and pitched it toward the cockpit, and it took 0.57 seconds to reach the front, you know that the exact same pitch in the opposite direction would also take 0.57 seconds to reach the back.

You know this. I know this. Einstein knew this. Galileo would have known it too—if he’d ever seen an airplane.

It’s simple. And yet the interpretation of this very simple situation—more precisely, the misinterpretation of it, as it’s been made in various ways—has misled thinkers for centuries.

It once convinced humanity that Earth must be motionless at the centre of the cosmos, else we’d feel the effects of our planet’s swift motion. Galileo corrected that.

But at the beginning of the twentieth century, Einstein fumbled the interpretation again, just as Aristotle had done. And in the process he convinced physicists and philosophers that there is no such thing as “now,” and that the passage of time itself is a grand illusion.

This essay will unpack Einstein’s mistake and explain how relativity must be interpreted if it’s to be consistent with the available evidence.

Does the ball really take as long to hit the back wall as the front?

Let’s go back to the idea where you’re pitching balls from mid-cabin.

And let’s imagine to start with that the plane isn’t really cruising along at 300 metres per second. Let’s assume a different convention. We’ll take the plane to be perfectly still, suspended in the air, while the ground beneath is actually moving 300 metres per second in the opposite direction.

Our ability to establish a specific inertial convention is similar to the way we’re able to set our minds to see either animal in the famous rabbit-duck illusion.

You can easily imagine this, reconciling this convention with experience. Just think back to flying again. Sitting there in your seat, nothing around you in the cabin appears to be moving at 300 metres per second. It’s all relatively still. Particularly with the windows closed, you can easily imagine that you and everything around you is at rest. That’s what it means to be inertial.

And even if you do look out the window, in this frame of mind you can convince yourself that you actually are at rest while the ground below zooms along.

Mentally, our ability to establish a specific inertial convention is similar to the way we’re able to set our minds to see either animal in the famous rabbit-duck illusion. It’s a simple matter of perspective.

Your choice of perspective is irrelevant to your local physics. The principle of relativity ensures the description from this perspective must be equivalent to the description from the perspective in which the plane is conventionally understood to be really moving.

With the plane perfectly at rest, it is clear that if you stood in the precise centre of the cabin and threw the ball to the back wall, then turned around and threw the ball with exactly the same speed, again from the centre, it would take exactly the same amount of time to reach the front wall.

In an ideal scenario, you could imagine constructing a perfect pitching machine: one that pitches two balls in opposite directions at exactly the same time with exactly the same speed. If you put this in the exact middle of the cabin, then of course the two balls will reach the back and front walls at exactly the same time.

Equivalently, and more realistically, you could put a light bulb in the exact centre and flick it on. Clearly the photons from the bulb will reach the front and back walls at the exact same time, having travelled the same distance at the same speed in both directions.

Now, let’s establish a new convention for “rest” and describe the same scenario.

In this case, imagine that the plane is now moving—that it’s now flying above the fixed ground at 300 metres per second. You can imagine this either from the perspective of being on the fixed ground, seeing the plane move above, or from an onboard perspective, looking out the window and seeing the ground move, but interpreting that as your own motion relative to the fixed ground.

In essence, whereas you previously described everything as a “duck,” you’ve now decided that the world is a “rabbit.” Having established this alternative convention, let’s repeat the same set of experiments.

When the plane is conventionally understood to be moving, the ball travels a shorter distance and takes a shorter amount of time to travel to the back of the plane, and it travels a longer distance and takes longer to travel to the front of the plane.

First, when you stand in the middle of the cabin and pitch the ball at the back wall, it’s clear that, after it leaves your hand, your hand continues to move forward, along with the plane, because you have the same inertia.

In fact, so does the plane continue to move. From the moment the ball leaves your hand until the moment it hits the back of the plane, that back wall will have clearly moved toward the point in space where the ball left your hand.

Therefore, the ball does not have to cover the whole distance, from the point where it left your hand to the point where the back wall was when the ball left your hand, by itself. The distance between the centre of the plane and the back, which you can measure, is still the full distance that must be travelled in order for the ball to hit the back wall. But from this perspective—this new convention you’ve established for interpreting “space,” “motion,” and “rest”—over the course of the ball’s flight that distance is covered in parts by both the ball and by the back wall.

In essence, during this interval, both the ball and the back wall travel in space, moving relative to each other and relative to the points where the ball left your hand and where the wall was when the ball left your hand. And over the course of this interval they come to be the same point; the ball and the wall collide with one another.

And, significantly, because the wall moved towards the point where the ball left your fingers, the ball did not have to make up the full initial distance on its own. The wall “helped” it out because it, too, was moving.

Therefore, the distance travelled by the ball must be less than the instantaneous distance between your fingers and the wall at the time the ball was thrown. This is intuitive and clear, given the established convention.

Now, what about when you throw the ball in the opposite direction?

In that case, the opposite is true. After the ball leaves your fingers, the front wall continues away from the place it was when the ball left your fingers. As a result, the ball has to travel further than that instantaneous distance before it will collide with the wall, because it effectively has to overtake the forward-moving wall. It travels further, and therefore takes longer than it would have had to if the wall had remained where it was at the instant the ball left your hand.

Therefore, when the plane is conventionally understood to be moving, the ball travels a shorter distance and takes a shorter amount of time to travel to the back of the plane, and it travels a longer distance and takes longer to travel to the front of the plane.

Whether two events are described as synchronous or not depends on the conventions of ‘space’ and ‘rest’ one assumes a priori. Synchrony follows identically from the assumed convention.

In this scenario, then, when using the same contraptions that were used in the previous scenario, the outcome is different.

When you use your perfect pitching machine, the balls do not arrive at the front and back walls at the same time. The ball that heads towards the back arrives first, and the ball that goes towards the front arrives later.

After you turn on the light bulb, the photons that move towards the back arrive first, and those moving towards the front arrive at the front wall later, having taken a longer time to travel an overall further distance.

All of this simply depends on the convention you establish to define what is “at rest” and what is “moving.” If you say that the ball really takes as long to hit the back wall as it does to hit the front, that’s because you’ve already previously committed to the convention that the plane is really at rest and the Earth is really moving. If you say the Earth is actually at rest and the plane is moving, then the ball takes less time to reach the back than it does the front, and if the two are thrown at the same time the one at the back hits before the one at the front.

Whether two events are described as synchronous or not depends on the conventions of “space” and “rest” one assumes a priori. Synchrony follows identically from the assumed convention.

The Relativity of Synchrony as a General Consequence

The relativity of synchrony established above is not particular to Einstein’s theories of relativity, nor is it tied to light or the light postulate. It’s a more general result, which depends only on the geometry and kinematics of relative motion.

The relativity of synchrony is not a feature of Einstein’s light postulate—it’s a more general consequence of how we define motion and rest.

The general conclusion, illustrated by the thought experiment above, is that there is a one-to-one correspondence between one’s definition of “rest” and one’s definition of “synchrony.” Two events described to occur synchronously in one reference frame do not occur at the same time in another frame where a different definition of rest has been assumed, and vice versa.

In fact, as opposed to more familiar considerations involving photons, the above thought experiment shows that this general consequence is true even when the speed of the “ball” is less than the speed of the “plane”.

In the thought experiment, when the plane is defined as moving at 300 m/s, that is much faster than any human can throw. A 100-mph fastball only moves a little over 40 m/s. Therefore, when you “throw the ball to the back of the plane” what you’re really doing is putting all your might into slowing its 300-m/s inertia—slowing it up so the back of the plane which is moving at 300 m/s can overtake and run into the more slowly moving ball.

Similarly, in the other direction you’re really just speeding the ball up, again by definition, so that by moving even faster than the front wall which is already moving at 300 m/s, the faster moving ball can catch up and hit the wall.

When we use photons instead of balls in this same thought experiment, two things happen. First, the photons aimed at the back of the plane actually move in that direction since they move at 300 million m/s rather than just 40 m/s. Therefore, if the plane is treated as moving through space at 300 m/s in one direction, the photons travelling towards the back of the plane are, by this same convention, moving in the opposite direction.

This observation is not specific to photons, but must be true for any “ball” whose speed is greater than the plane speed.

But it also has no bearing on the general result we’ve already established—that when the plane is conventionally defined to be at rest, the balls reach the back and front of the plane synchronously; and when the plane is conventionally defined as moving, the ball moving to the back will reach the wall first and the ball moving to the front will reach that wall later. This result is true whether the ball moves faster or slower than the plane.

And since this relativity of synchrony is a general result that does not depend on the “balls” being photons, travelling at the speed of light, it is also not particular to Einstein’s light postulate—which is more specific yet.

The light postulate is a specific principle of Einstein’s theories of relativity that says the speed of light in a vacuum is the exact same value regardless of the conventional reference frame. In the frame in which the plane is understood to be at rest, photons from a light bulb in the centre will travel at exactly the same speed towards the front and the back. And in the frame in which the plane is understood to be moving, photons moving in both directions will still move, according to Einstein, at the same speed towards the front and back, and that speed will be the same as it is in the frame in which the plane is defined to be at rest.

But since the relativity of synchrony follows from frame conventions alone, and holds regardless of how fast the balls travel, it is clearly independent of Einstein’s specific light postulate. Therefore, the relativity of synchrony is not a feature of Einstein’s light postulate—it’s a more general consequence of how we define motion and rest.

What Does the Light Postulate Logically Entail?

Einstein’s light postulate has specific metrical consequences that can be scientifically measured. For example, assuming that the vacuum speed of light has the same value in every inertial frame leads directly to the conclusion that velocities cannot simply be added together.

Imagine again that the plane is moving to the right at 300 m/s and the pitcher throws a ball at 40 m/s relative to the cabin. In Newtonian thinking, an observer on the ground would describe these speeds as 260 m/s (toward the back) and 340 m/s (toward the front). But relativity alters this arithmetic. Speeds combine according to:

which ensures that even in the limiting case—when the pitcher turns on a flashlight instead of throwing a ball—both the observer in the cabin and the observer on the ground must measure the photons’ speeds as exactly the same value, c, in both directions.

This is where the hallmark “weirdness” of Einstein’s relativity begins. In Newtonian physics, velocities add in a way that matches our everyday intuition: throw a ball forward on a moving train and it moves faster relative to the ground. But the light postulate defies this logic. No matter how fast the source is moving, light is always measured to travel at c. That single fact—empirically grounded but conceptually shocking—forces a dramatic revision of how space and time behave. From this point forward, familiar things begin to twist.

The invariance of c affects measured lengths and times. The cabin itself is contracted relative to the ground frame. Clocks on the moving plane tick slowly relative to the fixed ground. Or, if the plane is fixed and the ground is moving, then it is lengths along the ground that contract, and the ticking of clocks on Earth that slow.

The light postulate introduces specific metrical refinements that determine how much clocks in different frames desynchronize and precisely how space and time must adjust to preserve the invariant light speed. These quantitative refinements are crucial for scientific tests of relativity and allow predictions—such as those confirmed by modern GPS—that distinguish Einstein’s theories from Newtonian physics.

Once grasped, the relativity of synchrony feels natural—much like inertia, which puzzled thinkers for millennia but becomes intuitive once understood.

But the fact that two events can be synchronous in one conventional rest frame yet asynchronous in another is not something Einstein’s light postulate causes—it’s a general consequence of relativity itself. And while it’s not an obvious fact (it takes reasoning through the geometry and kinematics to see it), it is not “weird” in the way the light postulate is. Once grasped, it feels natural—much like inertia, which puzzled thinkers for millennia but becomes intuitive once understood. The light postulate fixes the numbers and dictates exactly how much desynchronization occurs; the very possibility of relative synchrony comes first, and follows straightforwardly from the choice of rest frame.

And indeed, every one of these pieces—conventional rest, relative synchrony, the light postulate and its metrical consequences—leaves untouched the deeper question: does relativity itself require simultaneity to be relative, or only synchrony? That is a separate, ontological issue we will return to below, once we’ve established clearly relativity’s scientific limit.

The Science of Relativity

Einstein’s theories of relativity have been extraordinarily successful as science. Countless experiments have confirmed their quantitative predictions: time dilation has been measured in particle accelerators and on satellites; length contraction and velocity-composition laws have been validated; even the subtle desynchronization of distant clocks, exactly as relativity predicts, is corrected for every day in the operation of the global positioning system. These empirical triumphs leave no doubt that the metrical consequences of relativity and the light postulate are scientifically sound.

But this success highlights an important limit: none of these experiments tell us whether we are really moving or really at rest. The relativity principle itself ensures that local experiments cannot distinguish a true state of rest; that any one provides a valid description of phenomena.

This limit again boils down to a general property of relativity—i.e. one that does not depend on the light postulate specifically. Therefore, as with the relativity of synchrony, it can be understood through a general qualitative thought experiment.

Even in the case where the plane is conventionally understood to be moving, in which case two balls thrown simultaneously reach the front and back walls asynchronously, by symmetry the balls return to the centre at exactly the same time. And this precise symmetry ensures that inertial observers must be incapable of ascertaining any truth of their own motion.

Returning to our pitcher-on-an-airplane scenario, just imagine what must happen in the case where the ball bounces instantaneously off of either wall and completes a round-trip journey back to the pitcher without losing speed.

In the case where the plane is defined to begin with as “at rest”, the result is trivial: if the ball never loses speed, it must take the same amount of time to return to the pitcher after bouncing off the wall as it does to reach the wall after being thrown. Both the ball thrown to the back wall and the ball thrown to the front wall will spend precisely half the time travelling to the wall and the other half travelling back to the pitcher.

The moving case is more interesting, and demonstrates a deep symmetry by which the relativistic effects cancel. As established above, if the pitcher uses a machine to launch the balls simultaneously towards the front and back, the ball headed to the back will reach the wall earlier than the one launched towards the front, due to the motion of the walls over the course of the journey.

But the exact opposite happens on the return journey.

The distance travelled from the back wall, at the time of the bounce, to the pitcher’s position when they later catch the ball, is the same as the distance from the pitcher when they throw the ball to the front wall when the ball hits it. The ball returning from the back wall to the pitcher is moving in the same direction as the ball thrown by the pitcher to the front wall. The return journey from the back wall to the pitcher must therefore take exactly as long as the journey from the pitcher to the front wall did.

Likewise, similar reasoning ensures the ball that bounced off the front wall will take just as long coming back to the pitcher as the other ball took to travel from the pitcher to the back wall. The outbound journey of the one ball takes the same amount of time as the inbound journey of the other ball, and vice versa.

Therefore, even in the case where the plane is conventionally understood to be moving, in which case the two balls reach the walls asynchronously, by symmetry the balls return to the centre at exactly the same time.

And this precise symmetry, which is a structural property of relativity in general, ensures that inertial observers must be incapable of ascertaining any truth of their own motion, whether by bouncing signals off their surroundings or by signalling to distant observers and receiving responses carrying information. Any amount of time gained or lost in the outbound travel of the signal is lost or gained symmetrically on the inbound signal, so the observations come to the observer just as if they were not moving at all.

When it comes to deciding whether a universal state of rest and a corresponding absolute simultaneity exist, local experiments have nothing to say.

If we replace the balls in this thought experiment with photons bouncing off mirrors, we therefore reproduce Einstein’s two-way light signaling procedure for clock synchronisation. This perfect symmetry guarantees that, by any such local experiment, you cannot tell whether it is the plane or the ground that is “really” moving. All you can establish is synchrony within your own reference frame—and from that, a conventional definition of relative rest—while motion relative to some external standard remains empirically hidden to such experiments.

This is the scientific limit of relativity: the theory allows us to measure differences in clock rates and spatial intervals between frames, and to confirm its precise metrical laws. But when it comes to deciding whether a universal state of rest and a corresponding absolute simultaneity exist, local experiments have nothing to say. That question is left entirely open from the standpoint of relativity.

The Philosophical Fork and the Naïve Realist Temptation

So far, we’ve established two key insights about relativistic physics in general:

- Synchrony is identically tied to a conventional state of rest: as soon as a state of rest has been specified, a corresponding definition of synchrony comes with it; and,

- One cannot empirically ascertain whether or not they are “truly” moving or at rest by sending and receiving signals from their surroundings. Instead, clocks synchronised through such procedures are implicitly tied to a local state of rest. This synchronisation procedure essentially identifies the associated conventional state of rest.

These observations can be explained in two different ways. That is, there are two logical alternatives by which, if true, these observations would naturally emerge as consequences.

From an empirical standpoint, relativity is fully consistent either with the convention of an objective ontological state of rest and an associated definition of true simultaneity, or with a convention by which motion is purely relative and the only meaningful definition of simultaneity is tied to frame-relative synchrony.

First, it is possible that there is one true state of rest, with a corresponding objective, ontological simultaneity (in contrast to conventional, frame-relative synchrony). In this case, an inertial observer who is by definition truly in motion will not be able to detect any sign of their motion through back and forth signalling with their relatively motionless surroundings. They will be able to detect when another system is moving relative to them, but could not determine through information that is passed back and forth whether either of them is truly at rest. They can synchronise clocks within their local reference frame, but just as they cannot determine that they are actually moving, they also cannot determine whether events they conventionally judge as synchronous are truly simultaneous. They do not have access to that ontological property.

Second, it may be that there is no true state of rest in reality, and therefore no corresponding sense of objective, ontological simultaneity. If so, then since both motion and synchrony are only relatively significant from the perspective of local scientific measurement, one is at liberty to say that there is no global definition of simultaneity in reality, but rather that simultaneity should be linked with synchrony and motion, as a frame-dependent quantity. In essence, in this case simultaneity is treated as synonymous with conventional synchrony.

From an empirical standpoint, relativity is fully consistent either with the convention of an objective ontological state of rest and an associated definition of true simultaneity, or with a convention by which motion is purely relative and the only meaningful definition of simultaneity is tied to frame-relative synchrony.

You cannot both conventionally define simultaneity as identical to synchrony and conventionally define yourself to be moving, even when you are certain that you are, and the world around you clearly confirms it.

While both interpretations are logically coherent, one may be inclined to prefer one or the other based on philosophical preferences. For instance, the frame-dependent option—that simultaneity is identical to synchrony—aligns fairly closely with a naïve realist instinct. For example, if you set up a lab and you conventionally define it to be at rest, you can synchronise all your clocks in the lab and by this convention you’d say that any two events that happened at the same time were simultaneous.

Similarly, if you are seated at rest on a plane, and you believe the plane is really at rest while the ground below you is really moving, then your naïve intuition will align with the convention that ties simultaneity to frame-relative synchrony. In essence, if you turn on a light bulb in the exact middle of the cabin, then the photons will indeed take just as long to reach the back as they will to reach the front, so they’ll arrive at the front and back walls at the same time. By convention, these two synchronous occurrences will also be said to occur simultaneously.

However, the frame-dependent option runs into a snag, and becomes inconsistent with the naïve realist perspective, in the case where you are seated at rest on a plane and you believe the plane is actually flying while the Earth is at rest. In this case, imagine that all the windows are closed before you are able to make any measurements and determine your speed, so you do know qualitatively that you are moving but you’re unable to measure your speed. From within the plane, you are unable to detect that you are at motion, and you recognise that you are in an inertial state. You can synchronise clocks, you can turn on the light bulb in the exact centre, and you will find that the light reaches the front and back walls at exactly the same time.

But in this case you know that the plane is actually moving, even though you can’t sense it or detect any effects of its actual motion. You know that after the light is turned on, and before the photons reach the ends of the cabin, the plane will have moved forward so the light will reach the back of the plane before it reaches the front. Conventionally, you understand that the two events are not simultaneous—but your clocks are synchronised with your local inertial frame so your measurements show that they nevertheless occurred at the same time.

And this is the crux of the choice—i.e. that it is a choice—a convention—and one that’s beyond the limits of scientific measurement—at least, by the measurements discussed so far, which rely on relaying information back and forth within a lab.

And neither of the two options is perfect—at least not in the absence of a confirmed state of objective rest. Lacking that, choosing the first option amounts to allowing that something we’ve not observed is nevertheless a true aspect of reality. On the other hand, the other option—the one that Einstein preferred—actively privileges one perspective at the expense of another, even when the “excluded” perspective is the one that matches unblinded intuition.

Just consider the three examples above, and let us draw on the analogy of the rabbit-duck illusion from earlier, as it exemplifies our common cognitive bistability—i.e. the brain’s ability to toggle between two equally valid but mutually exclusive perceptual interpretations.

In the first example, in which you’re working in a lab on Earth, let’s imagine that your natural perception of what is at rest is linked to the interpretation of the image as being “really” a rabbit. You synchronise clocks, run some experiments, and it all agrees with your intuition that you are really at rest and the image you see is really a rabbit.

The second example is of course absurd. No one flying in a plane believes that they are truly at rest and the Earth below is actually the thing moving. Our intuition anchors to the Earth as a natural state of rest whenever we see it—plus you know about gravity and planes that aren’t moving. We can think about this example as one where you look at the rabbit-duck image and convince yourself you’re seeing a duck. Even though you know it’s really a rabbit, the duck is still plain to see. And, if you synchronise clocks and run some experiments, because of the relativity of inertia and the relativity of synchrony you’ll find that they are all consistent with the “fact” you’ve convinced yourself of—that you “really” aren’t moving; that the picture is “really” a duck.

The third example is the one where you decide not to fool yourself. The picture is obviously a rabbit, even though you can see a duck if you reframe your perception. You obviously are moving, even though you can imagine you’re not since you’re in an inertial frame. And in this case, none of your experiments or conventional description align with your understanding of reality. You are moving; photons from a light that flashes at the centre do not reach the front and back simultaneously, yet they do reach the front and back at the same time. The picture is a rabbit—even if you can see a duck.

But you cannot both conventionally define simultaneity as identical to synchrony and conventionally define yourself to be moving, even when you are certain that you are, and the world around you clearly confirms it. Einstein’s preferred convention forces you to choose the duck even when you know it’s a rabbit.

The philosophical fork does not pose a straightforward choice in this. And the scientific evidence from local inertial experiments has nothing more to say—the picture can be either a rabbit or a duck, as far as science is concerned, whether you’re in the lab or on a plane. Based on the information we’ve considered so far, neither choice is more objective than the other.

In essence, because synchrony is empirically determinable locally, Einstein preferentially chose to identify simultaneity with it. Yet relativity itself ensures that one’s actual state of rest—if such a state objectively exists—along with its corresponding objective simultaneity, must remain inaccessible to local experiments. The absence of such evidence was taken as evidence of absence: a modal fallacy that elevated a philosophical preference to the status of being “more objectively” aligned with the evidence from local experimentation, when the correct conclusion should have been that both options are equally valid on the basis that local experimentation cannot distinguish between them.

Therefore, we must look elsewhere if we want a better answer.

Lessons from History

Relativity presents us with a logical fork. On the one hand, we have an option to choose, by convention, one specific definition of simultaneity. And in this case relativity tells us that events which occur simultaneously in reality will only occur synchronously from the perspective of observers who remain at rest in the corresponding rest frame. Any observer who is, by this definition, actually moving, will describe simultaneous events as occurring asynchronously; and the events they describe as synchronous will not occur simultaneously in reality.

On the other hand, we can collapse simultaneity entirely to a locally real concept, defining simultaneous events as the ones that occur synchronously in any given rest-frame.

The second option seems most closely linked to a naïve realist interpretation of reality. But even in that it fails, as it is inconsistent with naïve realist interpretations of inertial observers who believe they are really moving. This frame-dependent option is, in essence, only superficially naïve realist—it lets you treat your own frame’s synchrony as “simultaneity,” but collapses when you admit your frame might truly be in motion. The first option, however, adds a metaphysical layer to reality which is inaccessible to local experiment: since one cannot box themselves off inside a clean room and devise an experiment that would determine their “true” state of motion, this convention adds a constraint which it seemingly could never verify scientifically.

Faced with such a dilemma—a philosophical choice between two imperfect alternatives, that cannot be decided by the scientific evidence under consideration—the history of science (as explained in significantly greater detail in this essay) affords valuable insights.

Naïve realist interpretations should never be preferred by default when confronted with a purely philosophical choice.

First of all, we should not be hasty in choosing the naïve realist option. In the case of geocentrism, we did this. We inferred the obvious, lacking an understanding of relativity, that the Earth is at rest and everything moves around it. The stars appear to inhabit a two-dimensional sphere that circles around us once a day, and that’s how we interpreted them in reality. The Sun appears to circle the ecliptic once a year and we interpreted it as making this annual orbit around the stellar sphere. The outer planets appear to pause and reverse their usual eastward course, looping westward for a while and then returning to their eastward motion, and we interpreted this westward motion as real looping motion. It took nearly two thousand years from the first serious proposal that all of these should be interpreted as illusions due to our own real motion, spinning and orbiting around the Sun, before we finally convinced ourselves that the naïve realist interpretation was completely false. The most important lesson we can learn from the history of science is that naïve realist interpretations should never be preferred by default, when confronted with a purely philosophical choice.

History shows that we should not fear real underlying structure, even if we cannot yet detect it.

Second of all, for all these same reasons science has taught us that it is wrong to naïvely fear the possibility of real underlying structure that we’re unsure how to detect. Neither Aristarchus, nor Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, or Newton was able to directly detect that the Earth is orbiting the Sun. Kepler and Newton did eventually arrive at descriptions of planetary positions that were more accurate than the alternative Ptolemaic system afforded, but even they could not produce direct evidence that the Earth and planets are orbiting the Sun. The others were on even shakier ground in that regard because even their models were not more accurate from an empirical perspective. Yet each of them recognised that heliocentrism offered a more coherent alternative. And none of them were afraid to imagine that the Earth could really be moving in ways that could not be directly observed. That this supposed motion led to a simpler and more coherent account of the observed phenomena was enough for them to believe it must be true, and to explore the consequences.

The inability to measure a thing locally is not proof that it cannot be measured at all.

And third, while relativity ensures we cannot measure our own state of motion based on local experiments, passing information back and forth within an enclosed setting, that does not preclude any possibility that we can eventually detect a universal state of rest and measure our velocity with respect to it. Just as we can’t watch the Earth spin daily and orbit the Sun every year, but eventually we were able to measure annual parallax shifts in the positions of nearby stars as direct evidence that the Earth is actually orbiting the Sun, so too we may find direct empirical evidence of a cosmic rest frame, along with our motion through it.

In fact, it turns out that we do have exceptionally clear evidence of our own cosmic velocity.

Our Cosmological Motion

In the early twentieth century, viewing the universe as a vast sea of stars, each with their own relative motion, Einstein could not imagine that there could be a single, well-defined cosmic state of rest or that the universe would ever present us with a means of measuring our actual motion through it. He therefore committed to a frame-relative definition of simultaneity, defining it operationally in his 1905 paper On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies, where he concluded on the basis of that definition that simultaneity is synonymous with synchrony and therefore relative.

The fact that the universe did present us with a means of measuring our actual motion through it, and that we have subsequently measured our velocity through it with remarkable precision, is truly amazing. It renders Einstein’s simultaneity convention obsolete—a metaphysical red herring. And it has gone silently unacknowledged by philosophers who are too steeped in the wild goose chase resulting from this choice to even realise their overwrought arguments are outdated—that the illusion of choice has been superseded by empirical evidence.

The fact that our universe has a well-defined and empirically measured common state of rest is, in fact, so poorly recognised in the relativity community today (among both philosophers and physicists), that it warrants a careful explanation.

While the universe was thought to be static at the turn of the twentieth century, evidence that space is actually expanding began trickling in as early as 1913, when Vesto Slipher began observing radial velocities of the spiral nebulae from the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, AZ. By the early 1920s, the overwhelming majority of these were found to be moving away from us and the notion of an expanding universe had captured the imaginations of theoretical cosmologists. By the time Edwin Hubble measured the distances to several of these galaxies and in 1929 discovered his famous redshift-distance relation, the theorists were already prepared with an explanation.

Look around you, at whatever furniture or other objects are in the room with you right now. Imagine that in some finite time interval the whole room doubles in size while the objects themselves do not grow. A chair that was four feet away is now eight. The lamp that’s fifteen feet away is now thirty. When the room’s size doubles again, the chair is now sixteen feet away and the lamp is sixty feet away.

The further something is from you, the faster it will move away in each step—just as Hubble observed.

Both Slipher and Hubble had initially interpreted the observed redshifts as Doppler shifts, which are due to relative motion through space. They did not think of space itself as expanding, but imagined that the galaxies were actually all fleeing through space, with speeds that increased the further away they were.

In a sense, the velocity idea works according to the expanding universe model, since more distant galaxies do actually recede more quickly in an expanding universe. But the modern explanation of the observed redshifts is fundamentally different—an empirical phenomenon that is not directly related to the galaxies’ effective radial motions.

The Doppler effect results from relative motion of source and observer, and applies to any wave. It’s the reason why the noise from cars on a race track rises in pitch when they’re travelling towards you and drops when they’re moving away. The sound waves literally bunch up when travelling towards you because the waves and the source are both travelling in the same direction, so the wave crests don’t propagate away from the cars as quickly, from your perspective, as they would if the car weren’t partially keeping pace. The same happens with light waves: light from a moving source is observed with higher frequency when the source is approaching you and with a lower frequency when the source is receding. This lowered frequency is called redshift, since red is at the low-frequency end of the visible light spectrum (whereas blueshifted light has higher frequency due to motion towards the observer).

Within expanding space, galaxies are not actually moving through space, but are being carried away by the expansion of space itself, so they do not exhibit Doppler shifts. Those result from relative motion through space. Light from the chair and lamp is not redshifted because of their effective motion away from you; the redshift you’d observe is due to a fundamentally different mechanism. Similarly, if a distant galaxy has no motion through space relative to us, standard cosmology says that its light has no Doppler shift.

Instead, the cosmological redshift of light we observe is explained as a result of the photons’ motion through expanding space. It accumulates continuously as the light travels through expanding space, all after leaving the galaxy. As photons travel from a distant galaxy to us, their wavelengths are continuously stretched. They arrive at Earth with a redshift that depends on the amount of stretching the space between us has done throughout their journey. As long as space has been continually expanding, as the evidence suggests it has, then the observed cosmological redshift must increase as the galaxies’ distances increase, leading to Hubble’s redshift-distance law.

Now, the hypothetical form of this expansion that is assumed in cosmology, and the precision with which the standard model confirms its basic assumptions in this regard, are truly remarkable.

From a logical standpoint, the degree to which cosmic expansion is empirically confirmed to have been uniform throughout cosmic history entails an equivalent confirmation of the theory’s more fundamental hypothesis, that in reality there is actually a cosmic time and a globally well-defined state of rest.

The standard model begins with five basic assumptions. First, the galaxies are all assumed to have an average state of rest and a corresponding time-direction. This essentially sets up a cosmic definition of simultaneity through which an associated space is defined. Second, simultaneous events occurring in that space are assumed to be synchronous. Therefore, in the assumed cosmic rest frame, where a galaxy is not moving relative to the average state of rest we observe, simultaneous events really do occur synchronously. Third and fourth, the space so defined is assumed to be both isotropic and homogeneous—i.e. perfectly uniform, so it appears the same in all directions, from every point in space. And finally, this uniform space is supposed to expand or contract uniformly, at a rate that depends on the average densities of matter and energy within it, according to Einstein’s field equations of general relativity.

Of course, all of this is merely assumed—and these assumptions were in fact originally intended to account only for the large-scale average values we observe in our universe. They were never intended to hold with any great precision.

And yet they have, with truly remarkable precision that no one initially imagined possible.

I will explain the observational evidence behind that claim in a moment, but before I do it is worth explicitly clarifying the logical structure of this set of assumptions and how they connect to the empirical data. Specifically, the assumptions about space, its uniformity, and the particular form of its uniform expansion are all predicated on the more foundational assumption that there is a three-dimensional space, an associated state of rest, and a cosmic time.

Without that first assumption, nothing else can be defined. Without it, there is no coherent reference against which “spatial” uniformity or “temporal” evolution can even be defined. The second assumption—synchronous occurrence of simultaneous events—is a legacy of Einstein’s simultaneity convention and does not fundamentally define the spatial structure itself. It links model parameters to observational quantities, such as age and energy density, but does not bear on the reality of a cosmic simultaneity in the same way the first assumption does. I will return to this point in a future post.

For now, it’s enough to note that, from a logical standpoint—i.e. by the logic of the scientific method as much as by the structure of the model’s assumptions—the degree to which cosmic expansion is empirically confirmed to have been uniform throughout cosmic history entails similar confirmation of the theory’s more fundamental hypothesis, that in reality there is actually a cosmic time and a globally well-defined state of rest.

Now, consider the cosmic microwave background (CMB). Early in our universe’s history, it is understood to have been a uniform plasma. If we imagine the timeline of our expanding universe of galaxies in reverse, it contracts and matter comes together, eventually becoming quite dense and heating up. Eventually, it becomes hot enough to be like the interior of a star: atoms are moving so rapidly that the electrons are all stripped from nuclei and photons readily scatter off of them. But at the star’s surface, the atoms cool just enough that electrons can recombine with nuclei and are far less likely to interact with photons, so light can freely flow from the star’s surface.

The early universe was similar: photons moved around among the dense sea of electrons and atomic nuclei, easily scattered by them, so everything was in thermodynamic equilibrium and well-mixed—everywhere was essentially the same as everywhere else. But eventually, as the universe continued to expand and cool, it cooled just enough that the photons were no longer able to scatter off the electrons, the electrons recombined with nuclei to form stable atoms, and these photons could flow freely through the universe.

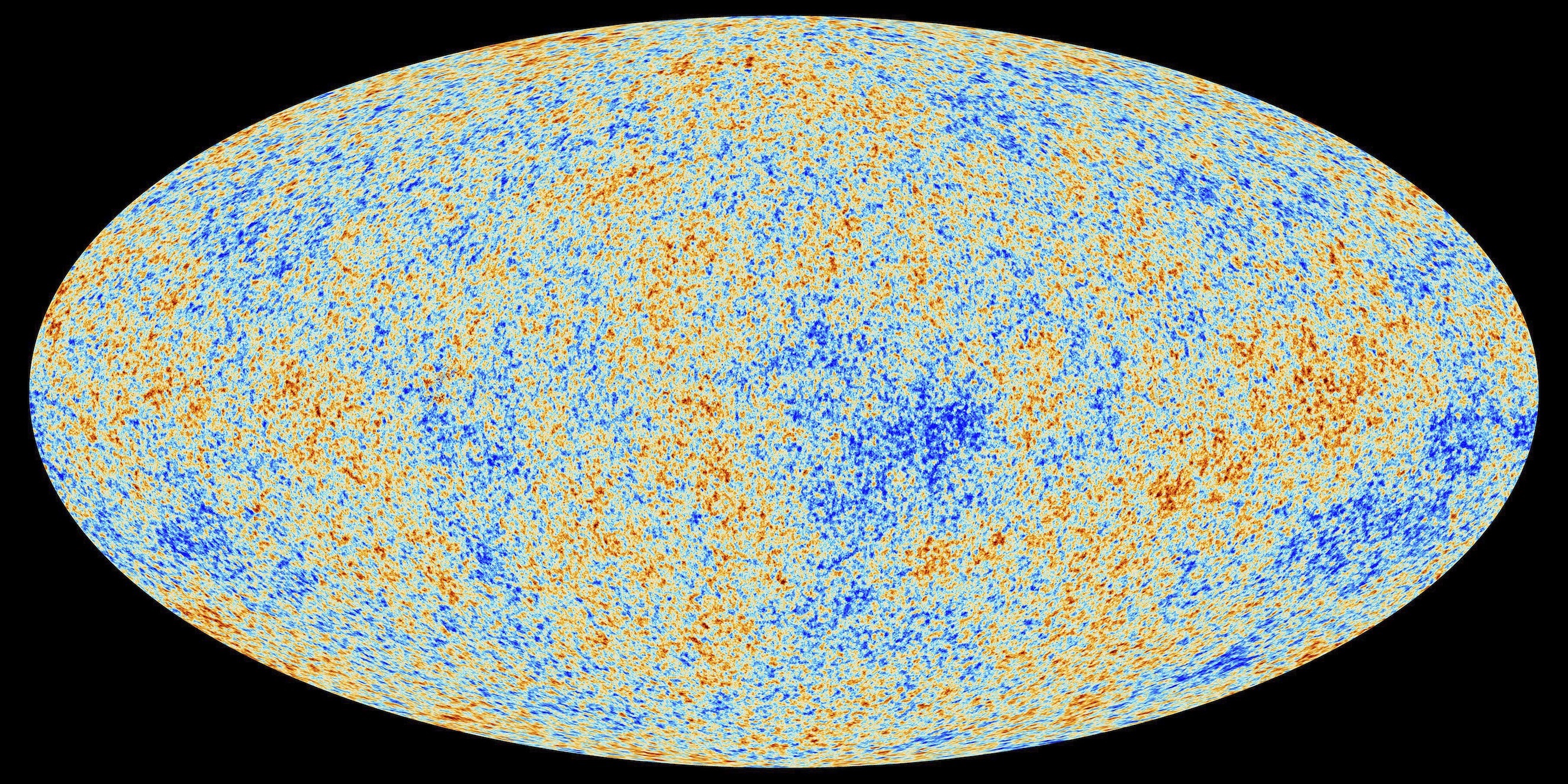

Today, those initially high energy photons have become the CMB. After recombination, each one was redshifted, continually over the course of 13.8 billion years as it travelled through expanding space—the cumulative amount of which depending on the integrated expansion of space the photon passed through. And the remarkable thing about the CMB is that no matter where we look in the universe, through directions that are mostly devoid of matter or through rich galaxy superclusters—which all should have affected the expansion of space differently in their local regions of influence—the total amount of redshift accumulated by each of the CMB photons, as they passed through these varied regions en route to Earth, is precisely uniform.

The actual universe is not a formless sea of randomly drifting stars. It has a dynamical structure, an evolving geometry, and a clearly defined state of rest through which its precisely uniform expansion is identified. Our Solar System is moving through the universe at 369.82±0.11 km/s towards the constellation Crater.

We actually do not even have an explanation for why this should be. But what we do know, very precisely, is that the CMB’s redshift is constant, no matter what direction we look. Therefore, either the expansion of space has been exactly uniform outside gravitationally bound galaxies and clusters, or, if it has varied locally, those variations must have conspired to cancel out to precisely the same value in all directions. The latter option is highly improbable, and would require a mechanism that could fine-tune all the varied cosmological redshifts so they emerge with precisely the same value today. But the former option, that the expansion of space actually has been uniform, also lacks an explanation since it is unexpected on the basis of general-relativistic dynamics.

Some models have even investigated what should happen if we take the apparent lumpiness of matter in our universe—the galaxies and clusters, voids and filaments—seriously in terms of how it should have affected cosmic expansion since the “recombination” era that produced the CMB. These find that the amount of cosmic expansion should have varied considerably across our universe, and should not have cancelled to anywhere near a constant value at present.

Yet this is directly contradicted by the empirical evidence of the CMB’s isotropic redshift. Therefore, regardless of the fundamental mechanism that drives it, the fact remains that either the universe really did expand precisely uniformly throughout cosmic history or an impossible fine-tuning mechanism caused all the local variations to cancel in our observations here and now.

So: to what level of precision do we know that the cosmological redshift of the CMB is isotropic?

The short answer is that any deviation from perfect isotropy in the integrated cosmological redshift must be less than one part in 100,000. The reason for this is due to a third redshift mechanism, one that occurred in the early universe, which has been preserved so it is still observable in the CMB today.

Back when the CMB formed we actually suspect the universe was not perfectly uniform—that there were very slight inhomogeneities in its matter density and it was not in exact thermal equilibrium. And these density inhomogeneities should have given rise to a third type of redshift—gravitational redshift—that occurred when the CMB photons escaped from denser regions of the cosmic plasma.

And even this prediction has been confirmed in the data. Our observations show that the temperature of CMB photons varies all across the sky in a manner consistent with the primordial anisotropy predictions, with its signature still present at a level of one part in 100,000.

These tiny variations were not erased greater differences in expansion rate that might have occurred over the course of subsequent expansion. Instead, every CMB photon we observe was redshifted by the same amount as every other one, with a uniformity that has remained so precise throughout the entire history of expansion that any deviations from perfect isotropy are not detectable at the level of these primordial anisotropies. Thus, the expansion of space in every direction we look must have been the same to a degree of more precise than one part in 100,000, otherwise the primordial anisotropy signature should have been erased.

And this precisely uniform expansion, as explained above, amounts to an equally precise observation that our universe does in fact have a well-defined state of rest. This state of rest is therefore not a large-scale average as originally supposed, but is in fact one of the most precise measurements in cosmology.

Einstein rightly noted that local experiments could not detect one’s “true” state of motion. And indeed, within the universe he imagined in 1905—one filled uniformly with stars moving in random directions with random speeds—this would not have been possible. But reality, it turns out, provided a way. The actual universe is not a formless sea of randomly drifting stars. It has a dynamical structure, an evolving geometry, and a clearly defined state of rest through which its precisely uniform expansion is identified.

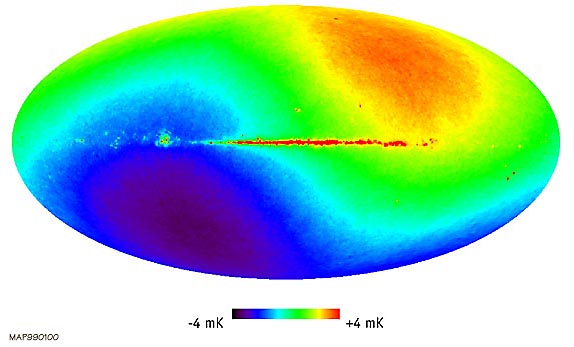

In fact, not only does the CMB allow us to identify that there is a cosmic standard of rest in our universe, but it actually gives a means of measuring our own relative velocity. Since we are actually moving relative to the CMB frame, we observe it with a Doppler shift—slightly redshifted in the direction we are coming from, and blueshifted in the direction we are going. From this, we infer that we are moving through the universe at 369.82±0.11 km/s towards the constellation Crater.

For over a century, generations of physicists and philosophers have doubled down on operational conventions and a purely relative ontology of motion—yet the universe itself has been quietly telling us otherwise. The “relativity of simultaneity,” long treated as a fundamental feature of reality, is instead a century-long detour—a wild goose chase. The universe itself shows that objective simultaneity is real, measurable, and cosmic in scale.

Objective Ontology Must Follow the Evidence

Ontological commitments must track empirical evidence objectively, wherever it leads. When the limits of science lead to a philosophical fork, the objective scientist would do well to honestly acknowledge when selecting one option preferentially over the other, noting clearly where evidence-based inference ends and subjective preference takes over.

In the case of relativity, historically this choice presented itself at the distinction between synchrony and simultaneity, and specifically whether there is actually an ontological distinction, or if the two should be treated as merely synonymous.

That choice should never have been framed as one between objectivity and preference, as it often has been, since both options amount to a choice that is not motivated by direct evidence. Rather, the one was motivated by a lack of evidence and a desire to avoid commitment to a non-evident structure which initially seemed outside the reach of evidence. The other, by a willingness to admit potential structure even if it could not initially be empirically confirmed; an acknowledgement that absence of evidence is not itself evidence of the absence of structure.

From a logical standpoint, neither option is “more objective” than the other. The system was merely underdetermined by the available evidence, and a preference could be chosen.

From the standpoint of objective logic and early twentieth century science, whether or not there is in reality a cosmic state of rest should have always remained an option on the table. The potential truth of this should have been admitted just as openly as the possibility that there is no cosmic state of rest.

From the perspective of early-twentieth century cosmology, it was reasonable to imagine that a random distribution of stars might not have a common state of rest. On the other hand, one might have noted that no star had been observed with relative speed anywhere near approaching the speed of light, as one would expect if stellar velocities were indeed purely random.

But such things were actually not seriously considered. And the logical fork was not objectively framed.

Instead, Einstein simply defined simultaneity as synonymous with synchrony. And the resulting “relativity of this simultaneity” was then taken as evidence that in reality there can be no objective “now,” and that the introduction of such a “preferred now” is not objective.

In time, what had always been—objectively—a preferential choice, settled into dogma. The notion of a “preferred rest frame” was disparaged as a subjective choice guided by flawed intuition. And the egalitarian option, that there is no ontological state of rest, and motion is purely relative, was viewed as the “more objective” choice.

From the standpoint of objective logic, this framing is a modal fallacy. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. In the absence of evidence that there is an objective state of rest in the universe, the two logical options are that there either is such a state of rest even though it is not evident, or there really is no such state of rest. Neither of these is “more objective” than the other.

The facts that synchrony is tied to a local state of rest, and that relativity ensures a potential actual state of motion is not locally measurable, do not together logically entail that there is no global state of rest and that simultaneity should be tied to frame-relative synchrony.

Yet this precise fallacy has been repeated for more than a century, and I imagine that Galileo has been rolling in his grave the entire time. His argument that Earth could well be actually orbiting the Sun and we’d not be able to detect that with reference to our local, relatively inert surroundings, was turned on its head. In its place, Einstein effectively argued that, given the same result, from the standpoint of relativity we should neither say that the Earth is orbiting the Sun nor that the Sun orbits the Earth, but only that both statements are equally true as a matter of relative perspective.

One might try to argue that the comparison is technically invalid because the Earth’s orbital motion is not inertial, but that is irrelevant: Earth’s non-inertial motions (daily spin and annual orbit) are insignificant in this context, since inertia is mainly responsible for the appearance that the world is relatively at rest, and the non-inertial spin and orbital effects are anyway insignificant relative to the local gravitational force. The fact remains that Galileo’s argument was that the Earth really is—in an ontological sense—spinning daily and orbiting the Sun annually, and that Einstein inverted the claim to say that if inertia is relative there can be no fact of the matter regarding one’s state of motion or rest, and motion should be treated operationally, assuming local conventions.

All of this is to say that from the standpoint of objective logic and early twentieth century science, whether or not there is in reality a cosmic state of rest should have always remained an option on the table. The potential truth of this should have been admitted just as openly as the possibility that there is no cosmic state of rest.

Had this been done—had we been open to the possibility that evidence might emerge through some other mechanism, in which we could scientifically identify a cosmic state of rest and potentially measure our own “absolute” velocity—we should have long ago recognised that there is indeed a cosmic standard of rest and motion is not purely relative.

By sheer force of cognitive dissonance, relativists have clung to the fantasy that motion and simultaneity are purely relative—that time and “now” have no cosmic reference. Scientific realism demands otherwise: metaphysical commitments must track empirical discovery. Nature has spoken—there is a real cosmic rest frame, and with it, an objective simultaneity.

In 1965, when Penzias and Wilson detected the uniform cosmic microwave background, we should have already recognised this as scientific confirmation not merely of an early dense state in our universe, but that the evidence had been preserved as the photons emitted at recombination travelled through the universe being continually redshifted through the expansion of space. We should have recognised the uniform present temperature of the CMB as evidence that the universe has been expanding uniformly since its creation, resulting in isotropic redshift.

And we should have inferred from this apparently uniform expansion, by the logical structure of the standard model and by the basic principles of scientific reasoning, that this observation amounts to empirical evidence of cosmological time and a corresponding ontological simultaneity—empirical evidence that undermines Einstein’s preferred choice.

In 1992, when COBE mapped the CMB’s uniformity, the fact that it is an isotropically redshifted blackbody, and that our own velocity through it is well defined through the Doppler-shifted dipole anisotropy, should have been viewed as decisive evidence that Einstein had chosen incorrectly, and any justification for his preference had vanished in the face of empirical evidence.

And finally, when WMAP and Planck precisely mapped the primordial anisotropy signature in the early part of the twenty-first century, and we found that these anisotropies at one part in 100,000 have been preserved in the course of continuous cosmic expansion over 13.8 billion years, this should have been identified as overwhelming evidence that the expansion of space over that entire period has indeed been uniform, as any non-uniformity would have erased the subtle anisotropy signature.

But none of this happened.

The relativity of synchrony has never been objectively regarded as presenting an ontological fork. Instead, Einstein’s preference has been treated as dogma while the “relativity of simultaneity”—the notion that there is no objective “now” in reality—has been revered as a triumph of scientific logic with fantastic consequences.

While the discovery of CMB was taken as decisive evidence that our universe has continuously expanded from a hot, dense state, with space expanding ever since—and while the empirical evidence has consistently shown, with increasing precision, that this expansion must have been precisely uniform—that space has been uniformly expanding throughout time—we have continued to convince ourselves that relativity must be taken to imply that there is no objective state of rest, no ontological simultaneity, no universal now against which relative synchrony must be compared.

By the sheer power of cognitive dissonance, relativists have continued to believe the fantasy that motion and simultaneity are purely relative, and that time and now have no cosmic standards of reference.

But scientific realism demands that metaphysical commitments track empirical discovery. It means discarding conventions when nature itself presents a deeper structure. The universe has told us: there is a real cosmic rest frame, and with it, an objective notion of simultaneity.

The evidence is clear: synchrony is relative; simultaneity is absolute. Einstein’s simultaneity convention was nothing more than a historically understandable but now empirically obsolete metaphysical detour.

Einstein’s Metaphysical Wild Goose Chase

Einstein envisioned a world without absolute rest, convinced that making motion ever more relative was the path to deeper science. His brilliance—and his success in explaining experiments—convinced generations that the choice must have been metaphysically correct.

He was so convincing that the modal fallacy his position rested on (i.e. absence of evidence is evidence of absence) has not been held against him. In fact, the common claim has been that a “preferred frame” amounts to additional, unobserved structure, and the more objective interpretation of the available evidence is that no such frame exists.

Then, convinced as we’ve been that a preferred frame can’t be observed as a matter of relativistic fact, when the universe presented us with empirical evidence and we spent six decades refining our measurements with increasing precision, generally we’ve failed to acknowledge the fact that the claim was empirically falsified long ago.

At the same time, Einstein’s relativity of simultaneity has not sat idly by as a fascinating, scientifically verifiable (in terms of synchrony), but otherwise ontologically benign insight.

It birthed concepts like the claim that if one could find a way to travel faster than the speed of light, time travel would be possible. This rests on the notion that if simultaneity were ontologically relative, then the set of events happening “now” throughout “space” depend on one’s relative motion. Therefore, while I might describe certain events as happening “now” on Andromeda, if I went for a drive the events happening “now” on Andromeda could be several days in the past. From that perspective, if I could travel “instantaneously” to Andromeda I’d arrive there several days in the past. Then, if I moved in such a way that “now” here on Earth happened to be several days ago, and I travelled “instantaneously” back to Earth, I’d get back here several days in the past.

Such incoherent messes as this are more clearly identified as such when the empirical evidence in support of an ontological “now” is taken seriously. Cosmologists describe the universe as currently being 13.8 billion years old. The Andromeda galaxy exists “now,” not several days ago. Going for a drive here on Earth does not change that. If we were capable of superluminal travel, then according to modern cosmology the result would be more like Star Wars than The Time Machine: we’d simply zip around our galaxy, arriving at places that evolved a little more in cosmic time than they were when we set out towards them.

Of course, physical effects like time dilation would still happen, and superluminal travel is not actually possible, so the situation is technically closer to the one described in the Ender series than in Star Wars. But regardless, the notion that ontological “now” is objectively defined in a manner that’s consistent with the cosmological evidence, does put a decisive end to the alluring possibility of the superluminal time travel fantasy.

Indeed, by the same reasoning used to justify superluminal time travel, physicists and philosophers have often claimed that relativity objectively supports eternalism, or the block universe theory, in which “the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.” This is because, just as “now” was understood to depend simply on one’s state of relative motion, every event that ever happens throughout eternity can be described as happening “now” from the perspective of some observer who exists “now” from our perspective. Therefore, if all events are objectively happening “now,” in some combination of “nows,” then all of eternity must be happening at-once and the apparent passage of time must be an illusion.

This block universe interpretation of the implications of relativity has been the source of endless debate this past century, in which proponents claim to be objectively considering the facts and the basic logic of relativity, while denialists rely on subjective experience and a “preferred” definition of now. But the claim fizzles and the debate dissolves on identification of the fact that an objective look at the logic never supported one view over the other, and that the empirical evidence actually strongly supports the idea of a well-defined ontological now.

In general, the concept that space-time “exists”—that it is the “fabric of the cosmos”—which is as universally believed at present as it is fundamentally incoherent, is essentially predicated on the idea that simultaneity is fundamentally relative and has no objective definition.

We’ve been chasing a metaphysical wild goose of science fiction and fantasy—one that long ago should have been recognised as logically flawed, absurd, and contradicted by the evidence. It’s time to face facts and correct course, leaving the idea of pure relative motion and its fantastic consequences behind us, once and for all.

Leave a comment