There’s a prevailing myth in the history of science that Copernicus rediscovered heliocentrism independently—and that he had no real connection to Aristarchus, whose own theory was vague, obscure, and uninfluential. This essay dismantles that myth.

While researching this previous essay, trying to get all my facts straight with reference to primary sources, I found several interconnected things that are badly misunderstood at the present—things I previously thought were true, but which closer inspection showed to be false.

I used to think, as it’s the common consensus, that it was unclear whether Nicolaus Copernicus had known Aristarchus of Samos proposed a heliocentric (Sun-centred) model similar to his in the third century BCE—and that he probably didn’t since he never mentioned it. But with some reading and piecing together of some related bits of evidence, and thinking about context, I’m now completely convinced Copernicus did know of Aristarchus’s hypothesis, and that he deliberately withheld acknowledgement of the fact.

Another thing I’ve always understood to be true, which is written all over the place, is that one of the main obstacles that stood against Aristarchus’s theory being accepted in his time was the fact that we don’t see any stellar parallax in nearby stars as Earth orbits the Sun. But this, too, turns out to be an anachronistic myth—and one that’s pretty clear to see when all the relevant information is pulled together. It’s also linked to a lot of inaccuracy related to interpreting Copernicus and Aristarchus, and in a way I think it has indirectly influenced the false consensus that Copernicus likely wasn’t aware of Aristarchus’s hypothesis.

Consequently, while this essay’s primary purpose is to explain that Copernicus was, without a doubt, aware of Aristarchus’s heliocentric theory—in fact, he was every bit as aware of its details as anyone today is—it will also clarify some other things that people seem to commonly misunderstand, such as the anachronistic parallax myth.

I want to be clear: I’m not claiming Copernicus originally got the heliocentric idea directly from Aristarchus. That is too strong a claim, and I don’t think we can ever know one way or the other. Aristarchus likely became known to Copernicus at some influential point during his studies in Italy, but whether that was before or after Copernicus had thought of the basic concept, and realised for himself that e.g. retrograde motion could be explained through parallax rather than by actual backwards motion as the planets looped around a fixed Earth, we cannot know. It is reasonable to think that Copernicus realised the latter on his own, though he did not keep a detailed diary as he worked through his ideas, so we can’t confirm this.

So we can’t know precisely when in his early years Copernicus became aware of Aristarchus, nor how influential the Ancient Greek had been in shaping Copernicus’s theory. In fact, very little is even known of the details of Aristarchus’s model, so it really can’t have been too influential. Copernicus must have come to realise much of what makes the concept so compelling on his own.

But still, this does not change the fact that Copernicus did Aristarchus dirty.

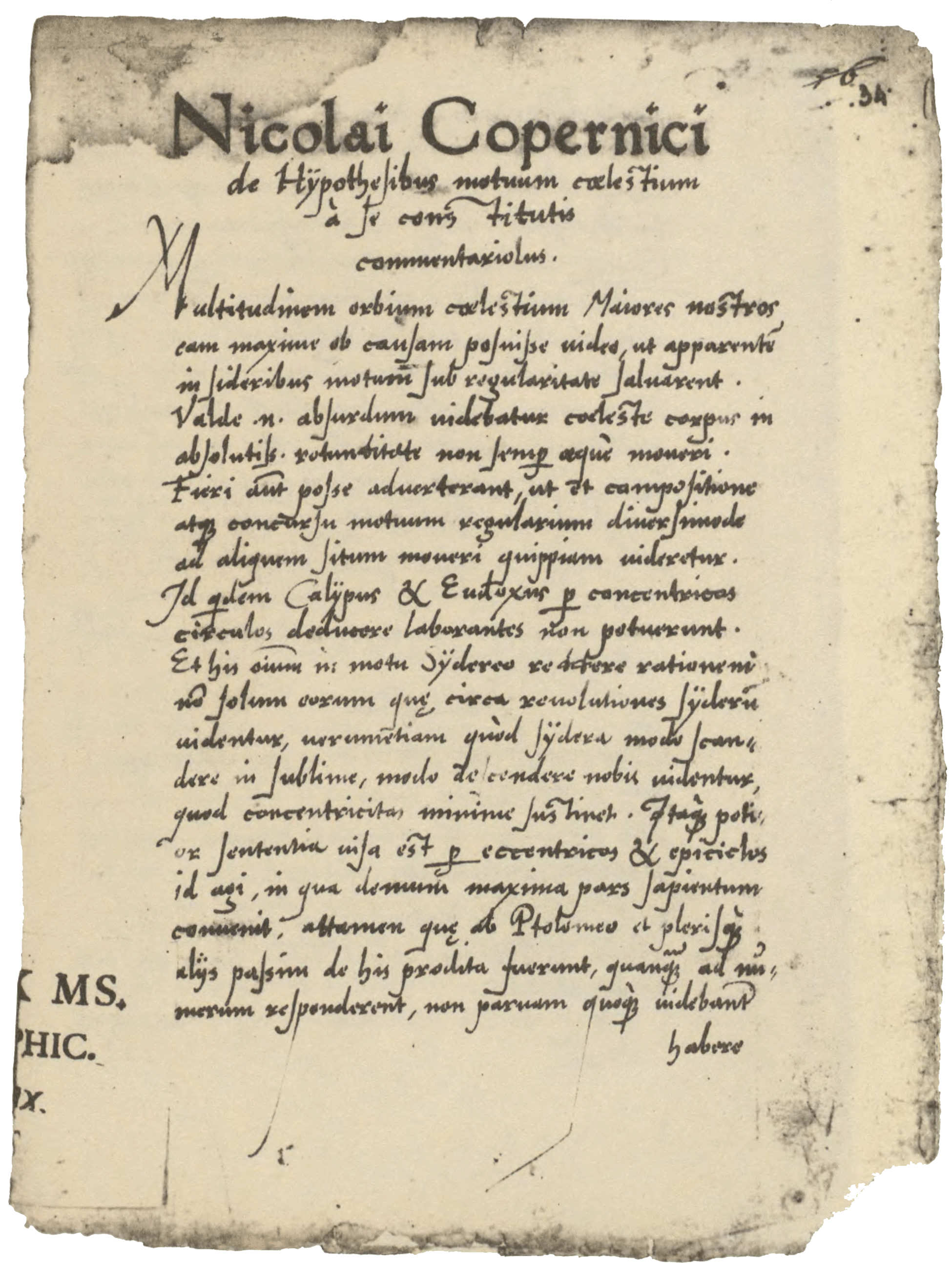

He knew Aristarchus had proposed a heliocentric theory in the third century BCE. He knew Aristarchus was a serious astronomer, e.g. the first to estimate the Sun’s distance through careful measurement and detailed geometric reasoning. And Copernicus deliberately withheld that information from both Commentariolus and De revolutionibus orbium coelestium—as he was absolutely aware of his predecessor’s theory already when he wrote his early draft.

This much is true. And it is also true that Copernicus made this omission so he could claim priority to the idea that the Earth orbits the Sun.

While he did not explicitly say this—how could he, as he omitted his knowledge of Aristarchus entirely?—he did so implicitly, by excluding Aristarchus from the broader group of Ancient geokineticists he listed in support of his proposal that the Earth moves, which he followed by explicitly claiming that he had come to the idea that Earth is orbiting the Sun on his own, “by long and intense study.”

Leaving Aristarchus out of that sequence worked well rhetorically, as he could cite precedent for the proposal that the Earth spins daily, or that it moves about a central fire in an abstract, metaphorical sense. And from there, Copernicus could frame himself as taking those ideas to the next level with a novel hypothesis that this moving Earth actually orbits the Sun.

The omission of Aristarchus provided a clean and compelling narrative within the opening argument for his life’s work, and it’s understandable that he did it. The alternative would be to frame the whole theory as something that had basically been thought of and explored in Ancient times, and eventually rejected by those who Copernicus and everyone around him thought of as intellectual authorities, leaving him to argue that while they’d eventually abandoned the idea he nevertheless proposed circling back to.

This more honest approach would have placed Copernicus at a much greater disadvantage, making him far more easily dismissed on superficial grounds, which he needed to avoid. “Check out my theory! Someone already thought of it 1800 years ago and the astronomers at the time eventually dismissed it as an abstract peculiarity that’s nevertheless absurd. But for the past several decades I’ve worked through the details anyway and I think I can make it work, never minding the absurdity which you’re likely to find insane.”

Copernicus actually acknowledged in De revolutionibus, that the idea that Earth was rapidly spinning and orbiting as he proposed seemed “absurd,” “insane,” and “almost against common sense.” To admit this, and to also say that people had nevertheless already considered the hypothesis and discarded it would have considerably heightened his disadvantage.

So, instead, he omitted the detail and framed the idea as novel:

“For a long time, then, I reflected on this confusion in the astronomical traditions concerning the derivation of the motions of the universe’s spheres… having obtained the opportunity from these sources, I too began to consider the mobility of the earth. And even though the idea seemed absurd, nevertheless I knew that others before me had been granted the freedom to imagine any circles whatever for the purpose of explaining the heavenly phenomena. Hence I thought that I too would be readily permitted to ascertain whether explanations sounder than those of my predecessors could be found for the revolution of the celestial spheres on the assumption of some motion of the earth… [and] by long and intense study I finally found that if the motions of the other planets are correlated with the orbiting of the earth…”

So you see: this narrative does not work if Copernicus acknowledges that Aristarchus had actually beaten him to the claim, and that Copernicus was reviving something that had been rejected almost two thousand years ago, by those who had the full original manuscript to work with. Omitting Aristarchus allowed Copernicus to cast himself as the innovator rather than revivalist—to frame heliocentrism as a novel hypothesis rather than a return to an abandoned theory.

Copernicus’s source on Aristrarchus’s theory—Archimedes’ Sand-Reckoner—was also not widely known when De revolutionibus was published in 1543. It was first printed (purely coincidentally?) in a Latin edition of Archimedes’ works in 1544. Copernicus was therefore not compelled to cite his source, as his knowledge of the former work was relatively private and not expected.

Anyway, the above explains roughly why I think Copernicus cut Aristarchus out. This is my reasoning based on Copernicus’s rhetorical framing of his proposal, and a suspicion that he was not acting purely in bad faith. Not necessarily because he wanted all the glory to himself, though there may have been some of that, but mainly because it would have been a disadvantage to do so.

But this essay is not about my own, personal speculative opinion. And I will not go so far as to demonstrate why Copernicus did what he did, nor how large a debt Copernicus owed to Aristarchus nor how much of his realisation about the compelling aspects of heliocentrism was original insight. I don’t think we’ll ever find more direct evidence to help in ascertaining these things.

What I will show, as I said above, is that Copernicus clearly, unquestionably did read Archimedes’ Sand-Reckoner sometime before 1514, when he circulated Commentariolus to his friends and colleagues—and that he therefore knew Aristarchus proposed a heliocentric theory before him. That he therefore deliberately withheld the reference in De revolutionibus. And that twentieth century Copernicus historians wrongly concluded he did not.

In the process, I’ll also set the record straight on a related point—a common anachronistic reading of the evidence that was held against heliocentrism, both in Ancient times and in Copernicus’s day. The idea that the Ancients cited an apparent asbsence of parallax shift in the nearest stars due to Earth’s hypothesised orbit about the Sun, that they favoured geocentrism in part because of this, and that Copernicus hedged against this criticism, is a complete falsehood that is almost universally accepted at present. This anachronistic parallax argument against heliocentrism was not noted until after Copernicus died—and in fact it was not even applicable to either his theory or Aristarchus’s. The fact that it is commonly thought to have concerned Copernicus and Aristarchus’s contemporaries is unfortunate for several reasons:

- it represents a fundamental misunderstanding of an Ancient worldview that persisted unchallenged until nearly the end of the sixteenth century, which Copernicus never dreamed of questioning;

- it therefore obscures the debt we all owe to one of the most influential innovations in the history of cosmology, to a person (Thomas Digges) whose name is hardly ever even mentioned in the history books—and certainly not as a key player in the Scientific Revolution—who frankly deserves to be celebrated as the father of modern cosmology, finally given his rightful place alongside Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, and Newton;

- it leads to anachronistic misreadings of both Ptolemy and Copernicus, when we fail to realise the notion of a parallax shift in nearby stars relative to those further away never could have crossed their minds; and,

- it obscures a key piece of evidence that renders Copernicus’s obvious plagiarism of Archimedes unmistakable, along with the deliberateness of his omission of Aristarchus as his predecessor.

It’s an interesting and deeply illuminating historiographic reset, and I hope you enjoy reading. It’s far more than just a detail about intellectual credit. These false narratives that have been propagating for more than a century warp our entire understanding of cosmological progress, Ancient science’s sophistication, and even modern assumptions about scientific reasoning.

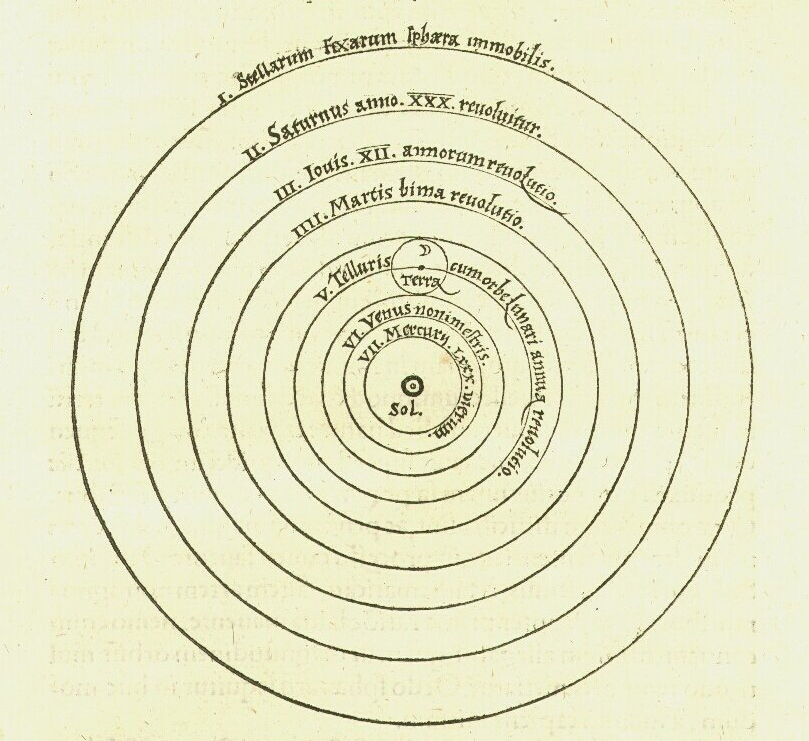

Given everything I’ve said above, I’ll work through the actual demonstration of claims as follows. I’m going to start with a recap of previous arguments that incorrectly concluded Copernicus was unaware of Aristarchus’s heliocentric theory, clarifying on their own terms how weak and flawed they are. I’ll then explain the anachronistic parallax argument, clarifying why it is an anachronism. With that context, we can then immediately clarify Archimedes’ reference to Aristarchus in the Sand-Reckoner—both, what his concerns were and what they were not. I’ll then also discuss both Ptolemy’s argument in Almagest Book I, Chapter 6 and Copernicus’s argument in De revolutionibus Book I, Chapter 6 (Copernicus deliberately paralleled the structure of Almagest as a rhetorical device in his work, so these chapters are similar), clearly establishing that neither was aware of the anachronistic parallax idea. Thus, we’ll clarify both, that Ptolemy was not arguing against heliocentrism on that ground—in fact, there is no evidence he entertained the heliocentric hypothesis at all in Almagest, as he never addressed it—and that Copernicus was not hedging against the anachronistic parallax argument in De revolutionibus—and again, there’s no evidence he ever even dreamed it was a problem he’d need to guard against—and in fact when we consider his actual worldview it’s clear the problem should never have crossed his mind.

We’ll then loop back to the Sand-Reckoner, specifically focusing on Archimedes’ application of Aristarchus’s theory, what that application says and what it explicitly does not imply about the Ancient reasons it failed to attract a wider following. In my previous essay, I gave three reasons why Aristarchus’s theory faded into obscurity until it was revived by Copernicus, and this diagnosis clarifies that the anachronistic parallax argument was never one of them—that it was never even dreamed of until after 1576, when Digges proposed his radically different cosmological worldview, which we’ve all come to accept implicitly, and tend to project onto earlier thinkers. Finally, having all these pieces in place, this analysis will close with the evidence that Copernicus lifted his fourth proposition in Commentariolus directly from Archimedes—that there is no other explanation for the specific formulation he chose, as he never would have come to that specific formulation on his own, he did not require it, he never made specific use of it, and in the end, in De revolutionibus he reverted to the less specific, mathematically imprecise argument that paralleled Ptolemy’s reasoning in the Almagest.

Previous Accounts by Science Historians

Copernicus’s Commentariolus was lost for more than 350 years. While he had shared copies privately with several friends and colleagues in 1514, those languished in private libraries. This first articulation of Copernicus’s heliocentric hypothesis was only rediscovered in 1878, by the historian Maximilian Curtze in Vienna. And it was first translated into English by Edward Rosen in 1939.

In 1942, Rudolf von Erhardt and Erika von Erhardt-Siebold published a sprawling article in the History of Science journal Isis, closing with a claim about “the almost certain acquaintance of Copernicus with the Sand-Reckoner.” In the article, this claim was buried at the end, and even there it was not well explained: The section is two paragraphs long, the point is made (without proper context) that Copernicus’s fourth postulate in Commentariolus is conspicuously similar in its construction to a passage from the Sand-Reckoner, and then the authors proceed to speculate—incorrectly!—that with this postulate Copernicus may have been guarding against the non-observability of stellar parallax due to Earth’s orbit.

The authors move on from there to speculate about the plausibility of Copernicus having had access to the Sand-Reckoner. They note that the potential accessibility had been considered by others who convinced themselves Copernicus could not have seen it. The argument they cite was that the popular printing of Archimedes’ works that included the Sand-Reckoner didn’t appear until 1544, so it was not widely accessible during Copernicus’s lifetime, and that Copernicus did cite others who proposed the Earth moved, but left out Aristarchus. The von Erhardts counter that “the argument is far from being unassailable,” as it is well-documented that the transcript existed, others were aware of its contents, and it had been shared and transcribed prior to Copernicus’s time in Italy, where he studied from 1496-1503; therefore, he could have obtained similar access. Furthermore, they observed that the fact that Copernicus did not name Archimedes or Aristarchus in connection with his fourth axiom from Commentariolus is inconclusive.

Later that same year, prominent historian of science Otto Neugebauer published a follow-up article. He noted that while the von Erhardts had “made it very plausible that Copernicus knew the Sand-Reckoner and could thus have been influenced by Aristarchus’ ideas,” the main purpose of their article—to question the authorship of the Sand-Reckoner—was itself less convincing and based on misunderstanding of the meaning in the text.

I think Neugebauer was right on both counts. And while the validity of the claim that Copernicus had known of Aristarchus through his reading of the Sand-Reckoner seems to have gone uncontested, in 1978 Edward Rosen followed up with a rather pathetic take of his own. His aim was to discredit the von Erhardts’ claim about Copernicus, and he spent the first half of the article simply reiterating points that the Sand-Reckoner was not readily accessible in print, and that if Copernicus had been aware of Aristarchus’s theory not only would he have cited it as he did others, “he would have leaped with joy.”

To the first point, regarding the relative unavailability of the Sand-Reckoner, Rosen noted that earlier in the fifteenth century Regiomontanus transcribed his own copy of the Sand-Reckoner while he was in Italy—though Rosen noted Copernicus could not have seen that transcript. He also noted that while Giorgio Valla both possessed a copy of the Sand-Reckoner and was known to Copernicus, Valla did not include a translation of the Sand-Reckoner in a volume of Archimedes’ works that Copernicus is known to have made extensive use of.

This argument relies on a modal fallacy: that the absence of evidence of a specific copy that Copernicus had access to amounts to strong evidence that he did not have access to any such manuscript. But the fact remains that the Sand-Reckoner was known to exist in Italy while he was there, and is known to have been made available to scholars who were interested in it. And in De revolutionibus, Copernicus tells us:

“I undertook the task of rereading the works of all the philosophers which I could obtain to learn whether anyone had ever proposed other motions of the universe’s spheres than those expounded by the teachers of astronomy in the schools. And in fact first I found in Cicero that Hicetas supposed the earth to move. Later I also discovered in Plutarch that certain others were of this opinion.”

Thus, both the opportunity and the desire were there during Copernicus’s 7 years in Italy. And while we don’t know the details, it is not unlikely under the circumstances that he should have found a copy.

Rosen’s second protestation actually seems to have been deliberately misleading, and the only explanation I can think of is that he idolised Copernicus as the “founder of modern astronomy” and was willing to lie in a misguided attempt to exonerate his hero.

In De revolutionibus, Copernicus mentioned four Ancient thinkers who had proposed the Earth moves in some fashion. Hericlined and Ecphantus, the Pythagoreans, along with Hicetus of Syracuse, were all credited with positing that the Earth rotates daily, and that this is the reason the stars appear to circle overhead. And Philolaus the Pythagorean was credited with postulating not only Earth’s rotation, but that it travels with several motions, that it is one of the heavenly bodies, and that, like the Sun and Moon, it revolves around the central fire in an oblique circle.

Rosen classified all of these generally as “geokineticists,” and noted that Aristarchus was conspicuously absent from Copernicus’s list of predecessors. He claimed the only explanations were that Copernicus did not have satisfactory evidence to group Aristarchus with the four other geokineticists or that he did have that evidence, and deliberately suppressed it. Rosen then oddly linked the affirmation of the latter to a crossed out passage in an early draft of De revolutionibus, in which Copernicus wrote “Philolaus was aware that the earth could move. Aristarchus was also of the same opinion, as some people say.” At this point, Rosen fully showed his hand. He wrote:

“These deleted lines make quite clear Copernicus’ unfamiliarity with the Aristarchus passage in the Sand-Reckoner. Had Copernicus realized that he could cite Archimedes as his authority for Aristarchus as a fifth geokineticist, he surely would not have submerged that renowned mathematician in an anonymous and undistinguished group of “some people” (nonnulli). Nor would Copernicus have confined his remark about Aristarchus to the earth’s mobility, had he learned about the additional features of Aristarchus’ astronomy from Archimedes’ report: the sun’s immobility and centrality, the stars’ immobility and enormous remoteness. Had Copernicus known that he could align the great Archimedes on his side, that he could add the distinctively Aristarchan insights to those proclaimed by the other four geokineticists, he would have leaped with joy. For he was painfully aware that, with the theologians and Aristotelian philosophers certain to denounce him, he needed all the support he could muster.”

This is utter bullshit.

For one thing, significantly, no one Copernicus named had proposed the Sun and stars are at rest and the Earth is the third of six planets orbiting the Sun. He framed that as his own novel proposal. For Rosen to lump Aristarchus in generally with the four other “geokineticists” conspicuously leaves out the significant fact that Aristarchus had specifically anticipated Copernicus’s heliocentric theory—not just any old geokinetic theory.

Rosen’s failure to acknowledge this detail is downright intellectually corrupt!

Second, Archimedes did not align with Aristarchus—in fact, he explicitly referred to “our cosmos” as “the sphere whose centre coincides with the centre of the earth and whose radius is equal to the straight line connecting the centres of the sun and earth,” which he contrasted with Aristarchus’s model in which the sun is at the centre of the fixed sphere of stars, and the earth follows a circular orbit with the Sun at the centre.

Finally, most importantly, Rosen never even mentioned the damning fourth postulate in Commentariolus. He never actually engaged with the specific claim made by the von Erhardts, the very reason why they claimed Copernicus must have read the Sand-Reckoner—which is damning as all hell! He simply skirted it while speculating adamantly to the alternative based on his personal opinion of what he felt Copernicus would surely have done.

He concluded with absolute resolve: “Copernicus was not aware of [the Sand-Reckoner] by Archimedes.”

A few years later, Copernicus’s most prominent biographer in modern times, Owen Gingerich, essentially reaffirmed Rosen’s opinions in his short article, “Did Copernicus Owe a Debt to Aristarchus?”

There, he began by essentially discarding the Sand-Reckoner as a possible text that Copernicus might have consulted, noted that there were in any case indirect connections between Aristarchus and Copernicus, but consolidated his focus to the question of “how much Copernicus might have known directly of Aristarchus, particularly concerning his heliocentric ideas.”

Gingerich proceeded from there to cite the most likely references to Aristarchus that would have been accessible to Copernicus, occasionally interjecting opinions about passages that may have been the only indication Copernicus ever had about Aristarchus as an architect of a heliocentric system, or that “Had Copernicus known of these references, particularly the latter one, he likely would have quoted it. But there is not a shred of evidence that Copernicus knew anything about Aristarchus as a heliocentrist except for the single rather cryptic passage…” Eventually, he concluded that it is not really the task of the science historian to “assess the comparative originality of these two scientific giants,” that neither had managed to convince their contemporaries, but that Copernicus had been fortunate enough to have his proposal taken up by later generations.

Finally, Gingerich concluded: “For better or for worse, scientific credit goes generally not so much for the originality of the concept as for the persuasiveness of the arguments. Thus, Aristarchus will undoubtedly continue to be remembered as “The Copernicus of Antiquity”, rather than Copernicus as “The Aristarchus of the Renaissance”.”

Again, Gingerich failed to engage with the damning passage from Commentariolus, and with that key omission arrived at a false conclusion.

The Anachronistic Parallax Argument

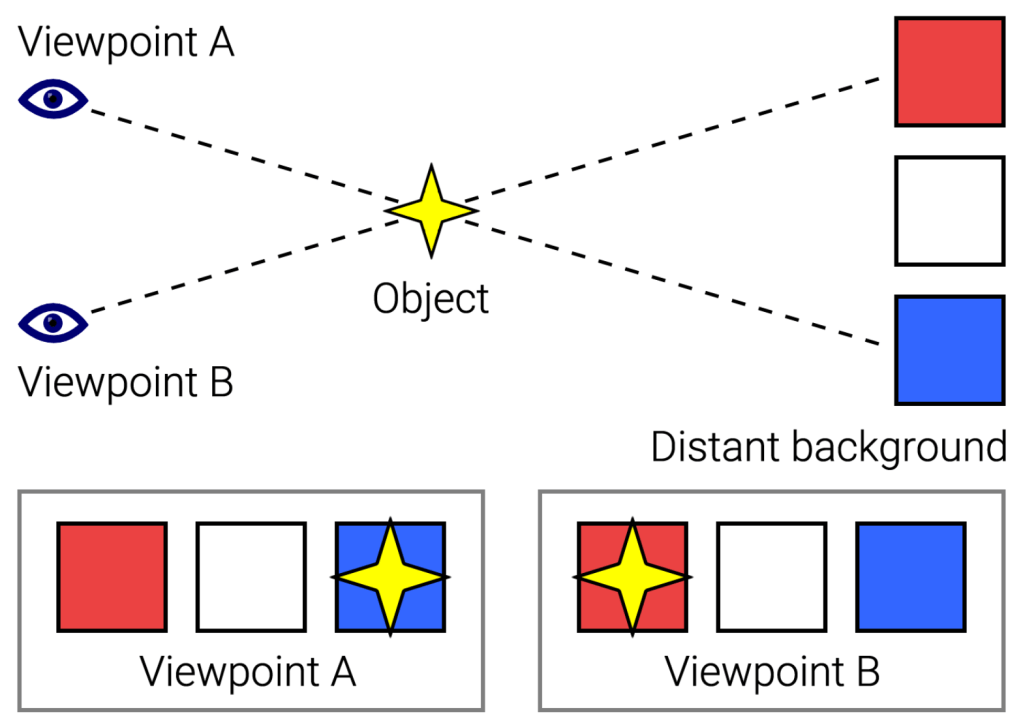

Because the Earth orbits the Sun, every six months our planet moves three hundred million kilometres from one side of it to the other. This motion induces a parallax shift in different stars, which is more prominent for nearby stars than it is for the ones further away.

To see this, take your two eyes as representing the Earth’s position at six-month intervals, with your nose representing the Sun. Hold your thumb in front of your face and wink back and forth so you see your thumb shift with that change in position, just as a nearby star shifts when we move from one side of the Sun to the other.

Now, extend your arm so your thumb gets further away. You should see that parallax shift get smaller and smaller as you do.

Similarly, we see stars hop back and forth when we monitor them over time. This is the most direct evidence we have that the Earth is actually a planet orbiting the Sun. But the stars are so far away, and the phenomenon is so difficult to observe, that even though everyone believed the Earth is a planet orbiting the Sun from roughly the turn of the eighteenth century onwards, it was roughly another 150 years before any parallax shift was confirmed.

Most recently, however, ESA’s Gaia spacecraft, launched in 2013, has measured parallax shifts in roughly 1.5 billion stars out to the edge of our Milky Way galaxy. Today, we are certain not only that this shift should happen, but that it does. In fact, it provides our most direct measurement of the distances to the stars, since there is a simple mathematical relationship between distance and the amount of parallax shift we observe.

So what’s the “anachronistic parallax argument”?

It is the idea that Ancient philosophers and contemporaries of Copernicus argued against heliocentrism on the basis that there is no observed stellar parallax shift; that in order for this to be true, either the stars must be unfathomably far away or Earth must be at rest at the centre of the universe.

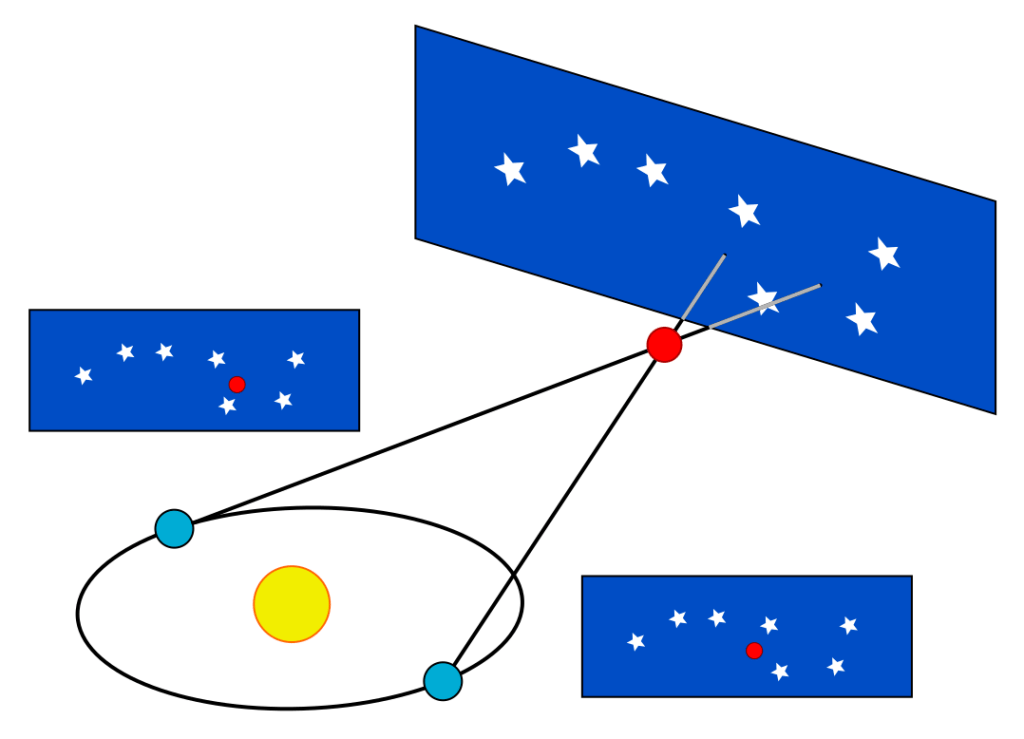

There are several reasons we can be certain that this argument was never made—that neither did the geocentrists argue against heliocentrism on the basis that we don’t observe parallax, nor did the heliocentrists argue that their model required a leap of faith in an absurdly large universe. First, neither Aristarchus’s model nor Copernicus’s actually implied that there should be relative parallax shifts between nearby and more distant stars; this notion comes from an anachronistic view of their cosmologies. Second, the actual stellar distances implied by measurement precision constraints weren’t even that incredible anyway. Third, Archimedes’ skeptical account of Aristarchus’s theory shows no indication that he was concerned about the large distance, yet he still did not accept the model. And fourth, neither Ptolemy nor Copernicus gave any indication that they had even thought of the issue, as becomes clear when we understand the true purpose of both Almagest I.6 and De revolutionibus I.6.

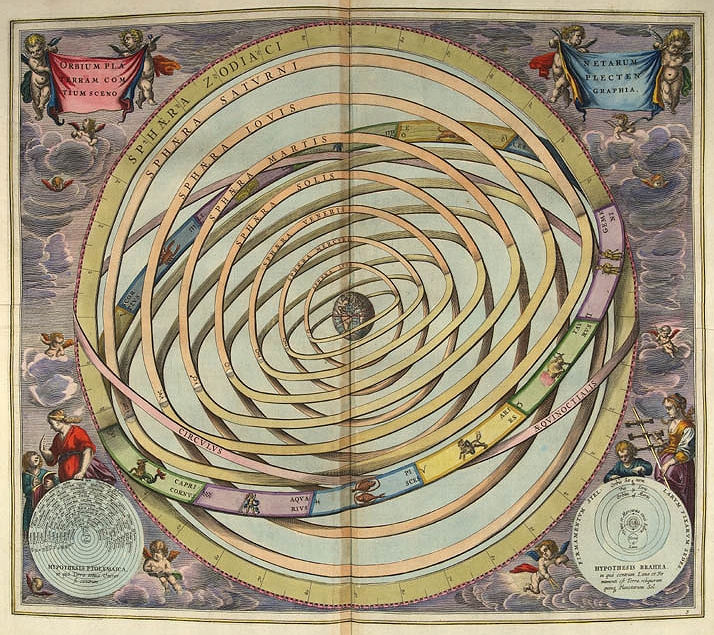

I. Parallax Was Conceptually Impossible in Ancient and Copernican Cosmologies

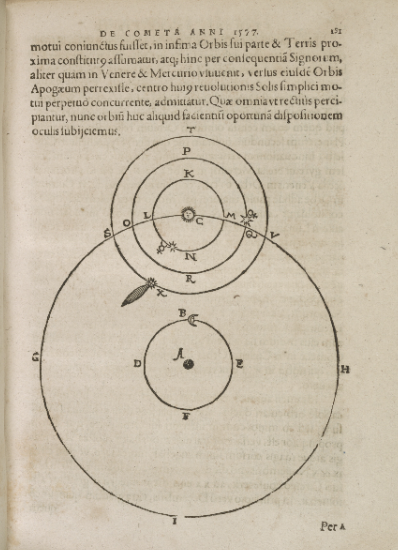

On the first point, it should be clear that the worldview that allows for parallax shifts to even become a potential issue is radically different from the one that Copernicus and all the Ancients held. In their view, the cosmos was composed of spheres in which all the heavenly bodies were either fixed or circled around their epicycles. In this view, the outermost sphere was the sphere of stars, a two-dimensional boundary of the cosmos, on which all the stars were located. This stellar sphere either circled the Earth once a day on its rotational axis (in the dominant view) or remained fixed while Earth rotated once a day inside it (in the view of the geokineticists Copernicus mentioned, along with Aristarchus, Copernicus, and likely some others).

Those were really the only two options, as anyone who studied the stars at all clearly saw that they were all circling uniformly, along arcs that varied in length depending on their distance from the poles, exactly as they would if fixed to a large spherical boundary. They were calling it as they saw it.

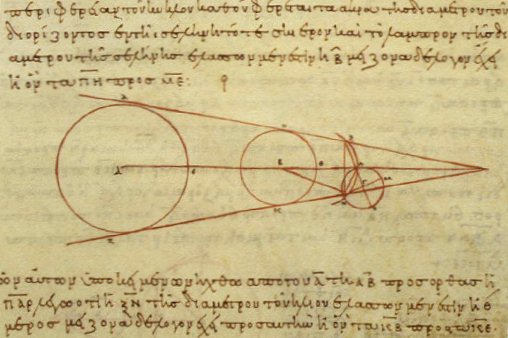

As far as I know, the first serious proposal to enter into this conversation, in which the universe was imagined to be fully three-dimensional with stars all at varying distances, was given by Thomas Digges in his 1576 English translation of Copernicus’s De revolutionibus. In the geocentric view, this simply had not been thinkable. The only way for the stars to all rotate at exactly the same rate was for them to be fixed to the same rotating spherical boundary. The idea of depth couldn’t cross anyone’s mind. Regarding Aristarchus, Archimedes makes it clear that he did not break from this tradition, that he too imagined a stellar sphere. And in both Commentariolus and De revolutionibus, Copernicus explicitly describes a similar stellar sphere, with no thought to giving it depth.

In this view, the notion of a relative parallax shift among stars at varying distances was incoherent; unthinkable. Neither Copernicus nor Ptolemy in their complete texts, nor any other extant text describing other Ancient models that I’m aware of, gives any indication that anyone even thought of the issue.

Digges’ idea of the cosmos was revolutionary: he was the first to dissolve the stellar sphere, scattering the stars through infinite space. Only in this post-Digges cosmos does it even make sense to ask whether nearby stars shift against distant ones as Earth moves. Therefore, it could only be after Digges, Bruno and others promoted the idea of cosmological depth, with stars radially distributed, that the idea even became thinkable.

Thus, the notion that the absence of observation of relative stellar parallax shifts was historically viewed as a problem for heliocentric theories is an anachronism—one that’s been projected backward from a post-Digges, infinite-space cosmos that was never imagined. Neither Copernicus, nor Aristarchus, nor anyone surrounding them thought of it because their heliocentric models simply halted the rotation of the stellar sphere and made the Earth rotate to give rise to the same apparent daily rotation. It was only after Digges added depth to the stars within the heliocentric view that relative parallax shifts even became thinkable.

II. The “Absurdly Large Universe” Myth Doesn’t Hold Up

To understand hypothetically what the implied “absurd distance” might have been, if anyone had even thought of the potential issue, we should consider what the actual constraint from the non-observation of parallax meant.

In Aristarchus’s time, a generous constraint on the angular positions they were capable of measuring is ten arcminutes. Some accounts suggest that Aristarchus put the angular diameters of the Sun and Moon at two degrees rather than half a degree, which would imply a significantly larger measurement uncertainty than ten arcminutes. However, this seems unlikely, so we will go with a more generous constraint and imagine that Aristarchus might have been able to detect a ten arcminute shift in a nearby star’s position relative to its neighbours.

Now, Aristarchus was the first to measure the distance to the Sun, and his measurement technique depended directly on his measurement of the Moon’s and the Sun’s angular radius. If the radius was one degree (implying a two-degree diameter), the distance to the Sun was 400 times the Earth’s radius. If the radius was more accurately taken to be one-quarter degree, the Sun’s distance increases to 1600 Earth radii.

The distance to the stars implied by parallax shift scales directly with the Earth-Sun distance. If we return to the idea that your eyes represent the Earth’s position on either side of the Sun (your nose) at six-month intervals, then you can imagine if your eyes were wider apart you’d see a greater parallax shift in your thumb (the nearby star) or if they were more narrowly set there would be a smaller distance.

A measurement precision of ten arcminutes means the stars would have to be near enough to us that they would move back and forth by this amount at six month intervals as we orbit the Sun. This corresponds to a factor of 344 times the distance to the Sun. Therefore, if the closest stars were more than 344 times as far from Earth as the Earth is from the Sun, Aristarchus and his contemporaries could not have observed a parallax shift. At this same measurement precision, the Sun was already 1600 Earth radii away from Earth. With the Sun’s distance already so much greater than the Earth, a further factor of 344 in the distance to the stars would indeed be significant, though surely not enough to be considered “absurd” or “incredible.”

By Ptolemy’s time, in the second century CE, the distance to the Sun was improved to 1210 Earth radii, while angular measurement precision was not significantly improved. At best, we can imagine Ptolemy might have been capable of three arcminutes precision rather than ten. In our hypothetical scenario, we can then imagine that if Ptolemy considered a Diggesian universe at all, he might have inferred the stars must be at least 1150 times further from Earth than the Sun is for no parallax shift to be seen at three-arcminutes’ precision. He might even have found the near-coincidence of this constraint and the Sun’s distance remarkable. However, there is no indication that Ptolemy or any of his contemporaries ever gave a thought to heliocentrism specifically, let alone a Diggesian world in which the stars were all radially distributed throughout infinite space and subject to this constraint.

Neither of these values were improved by Copernicus’s lifetime. Later in the sixteenth century, Tycho Brahe in particular had been capable of closer to one-arcminute precision in his angular measurements, multiplying the closest possible distance to the stars by a further factor of three. And Jeremiah Horrocks’ measurement of the Sun’s distance in 1639 through his transit of Venus observation extended that value by another order of magnitude, to 14,000 Earth radii.

Tycho seems to have been the first to formally argue against heliocentrism on these grounds, publishing this in his 1588 De Mundi Aetherei Recentioribus Phaenomenis. There, he argued that the non-observation of stellar parallax conflicted with his own stellar distance estimates. He had measured the apparent angular sizes of the largest stars were roughly two arcminutes. Therefore, he inferred that the stars must be incredibly large due to their implied distance, at least the size of Earth’s entire orbit around the Sun, or that the Earth is actually fixed. He famously preferred the latter explanation, offering it as support of his hybrid geo-heliocentric model.

Tycho’s technique is now known to have been fundamentally flawed (since the stellar diameters he observed were due to astronomical seeing, not true angular diameters of the stars, which are effectively points of light). Even so, he may have been the first to argue against heliocentrism on the basis of a non-observation of stellar parallax, following Digges’ introduction of the three-dimensional cosmological worldview in 1576.

III. Archimedes Was Not Concerned By The Size of Aristarchus’ Cosmos

Archimedes’ aim in the Sand-Reckoner was similar to that of the 1977 film, Powers of Ten. There, the scale of the universe is explored with logarithmic timing, starting from the size of a person, and then gradually working outwards to show how many times larger the Earth is than us, and how many times larger the solar system is than that, how much larger the Milky Way galaxy is than the solar system, etc. Then, the scaling reverses, eventually probing to sub-human scales, all the way down to atoms and then sub-atomic particles.

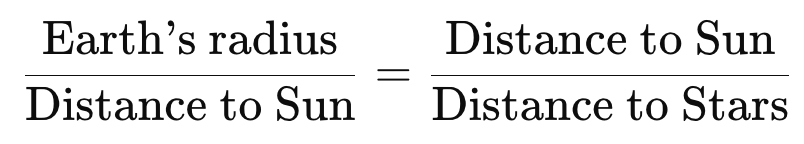

Archimedes was doing something similar, though with volume rather than length: he sought an estimate of the number of grains of sand that could be packed into the largest cosmos that had been conceived. To begin with, he noted that “our cosmos” extended from the centre of the Earth to the Sun, at the height of the celestial sphere. But, he noted that Aristarchus had proposed a model in which the Earth is a planet orbiting the Sun, with the Sun and stellar sphere fixed. According to this model, he noted that the ratio of the distance to the sphere of fixed stars and the distance to the Sun should be like the ratio of the surface of a sphere to a point at its centre.

A true mathematician, Archimedes then quibbled that this is obviously impossible since a point of magnitude zero can have no ratio to a finite length. Therefore, he revised Aristarchus’s second ratio to a comparison of the distance to the Sun and the radius of the Earth, leading to an equality of finite ratios. Thus, Archimedes suggested that in an Aristarchan universe the ratio of the radius of the stellar sphere to the distance to the Sun should equal the ratio of the distance to the Sun to the radius of Earth.

Note that this is a key piece of evidence that I’ll return to later, as it proves beyond reasonable doubt that Copernicus read the Sand-Reckoner, as he must have lifted this directly from Archimedes. Therefore, it proves Copernicus was fully aware of Aristarchus’s theory. Before coming to that, however, a few more points still must be established.

Now, by this time Eratosthenes had already produced an accurate measurement of Earth’s circumference, and Aristarchus had estimated the distance to the Sun. Therefore, Archimedes could have simply divided the square of the latter by the former to obtain a current “best” estimate of the size of the Aristarchan cosmos.

Using 400 RE as the distance to the Sun, in modern units this gives an estimate of 0.0001 light years. If we use 1600 RE instead for Aristarchus’s distance to the Sun, we get 0.002 light years. But neither of these estimates was large enough for Archimedes. He was looking not for the best estimate of the size of the cosmos, but the largest possible size that could be accommodated by existing measurements. His interest was in estimating how many grains of sand could possibly be packed within the cosmos—i.e. how much larger the cosmos might possibly be than a single grain of sand. Therefore, pulling together all the reasonable overestimates he could, he arrived at a much larger value, equivalent to 2 light years in our modern units.

Given his estimate for the size of the Aristarchan cosmos, Archimedes found that the universe could be as much as 1063 times the size of a single grain of sand. He did not comment on the absurdity of this difference, and crucially, he expressed no sense of disbelief about its scale—a silence that undercuts modern claims that cosmic size was an ancient objection.

In fact, Archimedes did not even offer a reason why Aristarchus required the ratio of the size of the cosmos to the Sun’s distance to be as the surface of a sphere to a point at its centre. He simply relayed that this had been Aristarchus’s requirement.

It is possible that this omitted explanation is partly to blame for the anachronistic myth that the Ancients had held the absence of apparent parallax shifts against Aristarchus. In that case, the argument could be that Aristarchus required this size to ensure that there would be no apparent parallax shifts in the positions of nearby stars. But this is clearly false, since neither Aristarchus nor his geocentrist contemporaries imagined a Diggesian cosmos; they all imagined the stars fixed to a spherical boundary, a uniform distance away from us, in which relative parallax shifts were unthinkable.

To understand why Aristarchus required Earth’s orbit to be as a point relative to the size of the stellar sphere, we need to turn to Ptolemy and Copernicus, as they explain the requirement.

IV. The Real Reason the Stellar Sphere Had To Be So Large

Ptolemy explained why the stellar sphere had to be large, even in his geocentric model, in Almagest I.1–6.

The first two chapters establish that astronomy is a branch of mathematics, uniquely capable of yielding certain knowledge about eternal celestial motions, and they lay out the logical structure of the treatise. Ptolemy begins by grounding astronomy philosophically, then explains that his analysis will proceed from general cosmological principles (Earth’s position, shape, and immobility) through the motions of the Sun, Moon, and finally the stars and planets.

Chapters 3 and 4 then establish that both the heavens and the Earth are spherical. Ptolemy argues first that only a spherical heaven can account for the uniform, circular daily motions of the stars and other celestial bodies, then demonstrates that Earth must also be spherical based on astronomical observations (such as eclipses and rising times) and practical evidence (like the gradual appearance of mountains to sailors).

In Chapter 5, Ptolemy provides a geometric argument showing that Earth must be positioned at the exact center of the heavens. He systematically rules out alternatives—being offset along the rotational axis, displaced toward one pole, or shifted in any other direction—demonstrating that such arrangements would distort observable phenomena like equinoxes, day lengths, rising and setting times, and lunar eclipses. Only by placing Earth at the center can the observed celestial motions and symmetries be preserved.

Finally, Chapter 6 establishes that Earth is vanishingly small relative to the heavens. Ptolemy argues that from any location on Earth, the celestial sphere is always divided into two equal hemispheres by the horizon, and star sizes and distances appear identical. Armillary spheres and gnomons set up anywhere function as if located at Earth’s true center. This universal symmetry would be impossible if Earth’s size were perceptible compared to the cosmic scale; thus, Earth has only the ratio of a mathematical point to the heavens.

Copernicus closely followed Ptolemy’s prescription De revolutionibus, similarly establishing, by the end of Book I, Chapter 6, that while the Earth “is not in the center of the universe, nevertheless its distance therefrom is still insignificant, especially in relation to the sphere of the fixed stars.” Like Ptolemy, he begins by elevating astronomy as the highest mathematical science, uniquely capable of providing certain knowledge about eternal celestial motions, and begins by establishing the spherical perfection of the universe and the Earth itself (I.1–2). He reinforces that land and water form a single sphere with a common center of gravity and argues that celestial motions must be uniform and circular (or compounded of circles), since only circles can account for their recurring, lawlike variations (I.3–4).

In Chapters 5 and 6, Copernicus departs from Ptolemy’s conclusion while preserving his logic. He questions the assumption that Earth must be fixed at the universe’s center, suggesting instead that its daily motions could arise from Earth’s own rotation. Yet he ultimately echoes Ptolemy’s geometric reasoning: horizons everywhere bisect the stellar sphere, lines of sight from Earth’s surface and center are effectively parallel, and the immensity of the heavens renders Earth’s size and displacement imperceptible. On the cosmic scale, Earth has only the ratio of a mathematical point to the fixed stars.

Crucially, nowhere in either text is an apparent parallax shift in the relative positions of the stars noted—neither as an argument against heliocentrism nor as a condition heliocentrists had to explain by postulating an exceptionally large stellar sphere.

Ptolemy never even considers heliocentrism directly. In Almagest I.7, he instead addresses Earth’s possible motion in general terms. Using the same reasoning Copernicus would later adopt, Ptolemy argues that Earth cannot be displaced from the center of the stellar sphere without contradicting observed symmetries. He explains that all heavy bodies naturally move radially toward Earth’s center, reinforcing its equilibrium at the cosmic midpoint. Finally, he dismisses the geokinetic view that daily rotation could be explained by Earth spinning on its axis, arguing that if Earth truly rotated, clouds, birds, and projectiles would appear to drift westward—an effect plainly not observed.

And Copernicus, following suit, never guarded against a potential rejection due to an extraordinarily large stellar sphere. In fact, he followed Ptolemy’s logic in Almagest I.1-7 carefully, noting for those same reasons that Earth’s motion must be essentially like a point at the centre of the stellar sphere. And those reasons had nothing to do with relative parallax shifts between nearby and more distant stars, as modern texts often imply. In fact, they can’t have since neither Ptolemy nor Copernicus ever imagined the stellar sphere had depth—they both thought of it as existing at a fixed radius.

Why Did the Ancients Reject Aristarchus?

In my previous essay, I discussed three main reasons why Aristarchus’s heliocentric model failed to gain traction, and explained how each obstacle was dismantled over the course of the Scientific Revolution:

- Reconciling a spinning and orbiting Earth with the overwhelming physical impression that it is at rest.

- The development of powerful predictive tools—Apollonius’s epicycles, Hipparchus’s eccentric, and Ptolemy’s equant—within the geocentric framework, which Aristarchus’s model lacked and which took Copernicus decades of work to rival.

- The radical interpretive leap required to treat many apparent motions as illusions caused by Earth’s own movement: the celestial sphere does not spin daily, the Sun does not orbit annually, planetary retrograde is not real reversal but parallax—all while other motions (e.g., Mercury, Venus, and the Moon) are real.

These obstacles were only fully overcome with Newton’s Principia. While point 3 recalls Plato’s Cave Allegory—our persistent tendency to accept appearances as reality—this pattern has rarely been treated as a central philosophical obstacle to scientific progress. In my earlier essay, I argued that our naive realism has repeatedly blinded us to deeper explanatory structures.

Notably absent from this list is the oft-repeated parallax objection to heliocentrism. I have now shown why: the ancient parallax argument is a modern myth, an anachronism projected backward into history. It has no basis in the ancient or Copernican worldview and should no longer appear in historical accounts.

Aristarchus in the Sand-Reckoner

With the anachronistic parallax myth dispelled, and with the true reasons clarified for why both Ptolemy (Almagest I.1–6) and Copernicus (De revolutionibus I.1–6) treated Earth or its orbit as effectively a point at the center of the stellar sphere, we can now return to the single ancient text that explicitly describes Aristarchus’s heliocentrism: Archimedes’ Sand-Reckoner.

Archimedes begins by noting that while most astronomers described the cosmos as a sphere centered on Earth, with radius equal to the distance between Earth and Sun, Aristarchus had proposed an alternative model in which the cosmos must be vastly larger. He writes:

“He assumes namely that the fixed stars and the sun remain stationary, while the earth moves round the sun through the circumference of a circle, which extends midway along its [apparent] track. Furthermore, that the sphere of the fixed stars is concentric with the sun and is of such size that the circle, through which he assumes the earth to revolve, has a ratio to the distance of the fixed stars equal to that which in a sphere bears the centre to the surface. Quite obviously, this is impossible. As the centre of the sphere has no magnitude, it is clear that it can neither have a ratio to the surface of the sphere.”

This passage establishes several things and warrants clarification. First, it is a clear summary of Aristarchus’s heliocentric model: the Sun and stars are fixed while Earth moves in a circular orbit. The phrase “which extends midway along its apparent track” is misleading. The original Greek, ὡς τι ἐν μέσῳ κείμενον, literally means “as though lying in the middle.” Thus, the statement should read:

“…while the earth moves round the sun through the circumference of a circle, as though [the sun] lay in the middle of it.”

Second, Archimedes specifies that the stellar sphere is concentric with the Sun—a two-dimensional boundary, not a depth-filled cosmos. There would therefore have been no relative parallax shifts to detect.

Archimedes then explains Aristarchus’s claim that the cosmos must be enormous: the distance to the stars is to the Sun’s distance as a sphere’s radius is to its center—a pointlike ratio. This is echoed nearly verbatim by Copernicus in De revolutionibus I.6, where he states that although Earth “is not in the center of the universe, nevertheless its distance therefrom is still insignificant, especially in relation to the sphere of the fixed stars.”

Finally, Archimedes raises a mathematical objection to Aristarchus’s phrasing. A point cannot have a ratio to a surface; a finite formula is needed to estimate the size of this heliocentric cosmos. Archimedes resolves it:

“In fact, we must understand Aristarchus to conceive the following… the ratio of the earth to the cosmos of our definition is equal to that which the sphere containing the circle of Aristarchus’s assumed orbit of the earth bears to the sphere of the fixed stars. In this way… he assumes the size of the sphere, in which he makes the earth revolve, equal to our cosmos.”

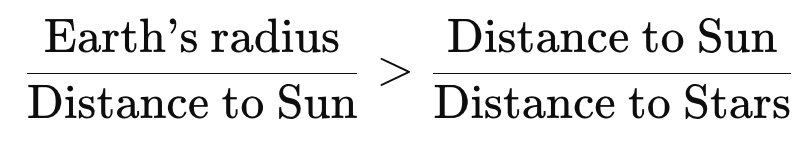

Thus, Aristarchus’s implied formula is:

Now, it’s important to note that in this context, this formula makes sense. The Sun’s distance was equal to the radius of Archimedes’ cosmos; therefore, the first ratio represented such a small value that all the effects Ptolemy would eventually discuss in Almagest I.1-6, several centuries later, would not be observed. Earth would be effectively a point relative to the size of Archimedes’ cosmos, just as it had to be to avoid the effects Ptolemy articulated, which must have been known already in Archimedes’ time. Therefore, if Aristarchus’s hypothesis were to be valid, his model required the size of Earth’s orbit to be similarly small compared to the size of his larger cosmos.

This equivalence of ratios compares how small one’s observing location must be, relative to the cosmos itself, for observed phenomena to remain unchanged. Since Archimedes’ cosmos ended at the Sun’s distance, this required Earth’s orbit to be as negligible within Aristarchus’ larger cosmos as Earth’s size was within the geocentric one. With this finite ratio in hand, Archimedes could extrapolate the largest possible size of the heliocentric cosmos from existing measurements.

Copernicus’ Tell

While the decisive evidence that Copernicus read the Sand-Reckoner lies in the specific formulation of his fourth postulate in Commentariolus, recent historiography adds a deeper layer of context. Bardi (2023) has shown that this earlier work was not yet shaped in the Ptolemaic mold of De revolutionibus, but rather structured as an Archimedean-style treatise. The draft’s axiomatic opening, concise structure, and mathematical tone reflect the intellectual environment of Renaissance Italy, where Archimedes’ works were being rediscovered and emulated. This broader Archimedean framing makes it all the more plausible that Copernicus had gained a deep familiarity with Archimedes’ writings by the time he drafted his early heliocentric theory. And the fourth postulate is the smoking gun that shows without a shadow of a doubt that Copernicus was familiar specifically with the Sand-Reckoner.

Swerdlow (1973) translates the fourth postulate thus:

“The ratio of the distance between the sun and earth to the height of the sphere of the fixed stars is so much smaller than the ratio of the semidiameter of the earth to the distance of the sun that the distance between the sun and earth is imperceptible compared to the great height of the sphere of the fixed star.”

Now, there are a few reasons I would claim that this is incontrovertible evidence that Copernicus read the Sand-Reckoner.

First, Copernicus had absolutely no reason to include the initial equation,

He effectively renders this equation, and then adds the clarifier that the inequality should be so great that the Earth’s orbital radius is imperceptible compared to the stellar sphere. But Ptolemy had gotten away with only the sloppier formulation, that his geocentric Earth’s radius was as a point compared to the distance to the stars, for 1400 years. Objections had not been raised that it was mathematically imprecise to compare infinitesimal and finite values. And by the time Copernicus wrote De revolutionibus three decades after Commentariolus, emulating Ptolemy rather than Archimedes, he dropped this unnecessary formula. But even in this early draft, he had no actual reason for including this formula, and he did not apply the specific formulation anyway.

Furthermore, in the context of Copernicus’s time, the first ratio he gave is actually incoherent. Why compare the Earth’s radius to the Sun’s distance in this context? What had made sense in Archimedes’ time no longer applied in Copernicus’s, where the dominant geocentric model was Ptolemy’s—not the single sphere cosmos of Archimedes’ day that placed that Sun at the same height as the stellar sphere. But in Ptolemy’s model, the spheres were nested, and they were all at different distances. The Moon was closest, merely 59 Earth-radii away from us. Then came Mercury’s and Venus’s spheres, and the Sun’s above that, which was 1210 Earth-radii away. Then Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and finally the fixed stars, which he placed at immeasurable distance.

Given that Copernicus’s purpose with this fourth postulate was to establish that the Sun’s distance is so miniscule compared to the radius of the stellar sphere, it is unclear, based on only internal logic, why it made sense to him to set the ratio of the Earth’s radius to the Sun’s distance (i.e. still 1/1210 in Copernicus’s day) as a finite upper bound, nor to connect them to the stellar sphere—those values have nothing to do with each other in this model.

Copernicus had no reason to include this formula within his fourth postulate in Commentariolus: he was neither compelled to for any reasons related to Ptolemaic astronomy, nor did he apply the formula afterwards. And the specific formula he chose to include sets the upper bound on the miniscule ratio he required, to a value that should have made little sense to him.

This formula is, however, nearly identical to the one given by Archimedes—differing only in replacing equality with inequality. Its appearance in Copernicus’s Commentariolus is therefore unmistakable evidence that he had read the Sand-Reckoner.

It’s a clear tell—a smoking gun—a quacking duck. Von Erhardt and von Erhardt-Siebold (1939) first noted this similarity; Neugebauer (1942) found the evidence very plausible even without the full context. Yet Rosen (1978) protested, Gingerich (1985) concurred, and what should have been a settled verdict has remained unresolved. By explaining the context, in particular exposing the anachronistic parallax myth that infects modern interpretations of these texts, the truth of the matter should now be clear. To state it plainly, then:

Copernicus read the Sand-Reckoner, was fully aware of Aristarchus’s heliocentric theory, and deliberately withheld attribution.

Leave a comment