Science, at its best, has always been an art form—a philosophical endeavor. We see what we see, and by comparing those impressions with everything else we know, we try to tease out what might be causing them. We keep observing, refining our methods, working to constrain and test the apparent data as precisely as possible—comparing the results against models based on the hypothetical causes we’ve inferred. Often, things don’t quite add up the way we thought they should.

Sometimes the process gets creative—or messy, or uncertain. And at its most transformative, it reveals that the very principles we’ve long taken for granted—the ones we believed were secured by overwhelming evidence, the ones we used to build our entire worldview—are false.

Plato captured this philosophical challenge with striking clarity over 2,000 years ago, through his Allegory of the Cave in Book VII of the Republic. In this story, a group of people live chained in place, their eyes fixed to the back wall of a cave. Behind them burns a fire, and objects passing in front of it cast shadows that the prisoners interpret as reality. Never having seen anything else, they learn to distinguish forms like “dog” or “cat” from the flickering shapes on the wall.

One day, one of them is freed and comes to see what’s really going on—that the shadows are not reality at all, but projections cast by real objects blocking the firelight. He returns to the others to explain, but they resist, unable to imagine any world beyond the shadows they know so well.

The history of science—astronomy in particular—is filled with episodes like this: moments where we’ve come to realize that the phenomena we observe are not the things themselves, nor even faithful representations of what’s real, but shadows cast by a deeper structure—distorted by perspective.

In astronomy, we rarely have the luxury of leaving the cave. Instead, we piece together the hidden shape of things by comparing shadows from different angles, demanding that our interpretations yield a coherent, self-consistent picture. But once we recognize the distortion for what it is, and sort out what’s really going on behind the scenes—when we find the correct explanation, the true cause of the shadows—our understanding deepens. We emerge with a more accurate, more coherent picture of reality.

Crucially, the right explanation doesn’t discard misleading phenomena—it reclassifies and explains them. It makes sense of the very appearances that once misled us, and does so consistently, without hand-waving or exception. It’s not enough to call appearances illusions and replace them with prettier stories. The test of understanding is whether we can explain why they appear as they do.

To extend Plato’s metaphor: the astronomer is like a cave-dweller who manages to free one hand. Holding it up into the light, they study its shadow on the wall, rotating and flexing it—inferring from its shifting silhouette that it’s cast by a real hand. By continuing to study these distorted projections, accepting them for what they are, and reasoning carefully about their limitations, they begin to learn the hand’s structure. From there, they infer that all the other shadows must likewise be projections of unseen things—and begin to form better understandings of the “dogs” and “cats,” along with their own hand.

Reading Earth’s Geometry from its Shadows

Take Earth itself as an example of how shadow-reading works. From our limited vantage, the horizon appears flat—but even here, there are clear signs that Earth is a vast sphere. Aristotle offered two in On the Heavens:

- During a lunar eclipse, Earth’s shadow is always round; and

- When we travel south, the stars shift northward—the pole star lowers toward the northern horizon, and new stars appear in the southern sky (replace north/south if observing in the southern hemisphere).

While point 1 could, in principle, be explained by either a spherical or a disc-shaped Earth, the disc hypothesis breaks down on closer inspection: if Earth were a flat disk, its shadow would change shape depending on the Moon’s position above the plane. But Earth’s shadow during an eclipse doesn’t change—it’s always a perfect curve.

Observation 2, on the other hand, only works if Earth is spherical. On a flat Earth, your north-south position wouldn’t affect your view of the stars.

Therefore, Earth’s shape logically must be spherical, as Aristotle reasoned.

A century later, Eratosthenes of Cyrene measured Earth’s circumference by applying principle 2. He compared the Sun’s altitude at the same time on the same day in two cities lying roughly along a north-south line. From the angular difference in the Sun’s altitude and the distance between the cities, Eratosthenes used basic geometry to calculate Earth’s circumference: roughly 40,000 km—which is, astonishingly, correct.

Since then, of course, we’ve launched spacecraft that have photographed Earth from orbit—offering a rare case of direct confirmation. In Plato’s terms, these images are like glimpsing the fire and the scurrying animals and seeing that the shapes on the wall are indeed shadows. But such moments of direct visual confirmation are rare in astronomy. Normally, we must infer the nature of the scurrying animals by doing detective work with only the shadows as evidence: we’re chained to the Earth, our eyes fixed on a sky that moves and shifts and transforms, night after night, as we remain fixed and relatively motionless; and we see only light that’s been projected by distant astronomical objects, not the objects themselves—but we use it to tease out the nature of those objects and the reality in which they exist.

The canonical example of how the scientific process tends to work—in fact, the story of how science itself came to be—is the story of how we discovered that Earth is a planet orbiting the Sun. That fact was only generally accepted relatively recently, toward the end of the seventeenth century. In fact, the most direct observational proof that we are actually moving around the Sun came much later still: the first measurement that nearby stars appear to shift slightly in position as we move from one side of the Sun to the other every six months came only in 1838—and precision measurements of this general shift, which decreases as stars get further from us, were only confirmed with the launch of space telescopes capable of the necessary precision in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

But long before this direct confirmation, astronomers spent two thousand years—culminating in two centuries of effort during the sixteenth and seventeenth—doing the detective work: observing the cosmos, constructing theories to explain the projections, and eventually—four hundred years ago—shattering the illusion that Earth rests at the universe’s centre.

This essay explains how that was done, and the important lessons we should take from one of the greatest achievements in the history of science, lest we doom ourselves to repeat past mistakes.

Ancient Astronomical Shadow Reading

Prior to the Scientific Revolution, all the available evidence was taken to suggest that the Earth is at rest at the centre of the universe. This was not a trivial inference, but one supported by a wide range of observations.

For one thing, ancient cultures around the globe were acutely aware of the nightly motion of the stars. Every star in the sky follows a concentric arc, making one revolution per day about an axis that runs through the centre of the Earth, from the north to the south pole. Stars near either pole trace small circles and never set below the horizon, while stars near the celestial equator trace the largest arcs—all travelling at the same angular rate.

Near the beginning of spring or autumn, when days and nights are equal in length, a star that is just rising in the east at dusk will travel all the way around the sky and set in the west at dawn.

While much of the world’s traditional sky knowledge has been lost, some of the scientific and philosophical investigations of ancient Greek and Mesopotamian cultures have survived. The best source of this knowledge is preserved in Ptolemy’s Almagest, a second-century CE treatise on mathematical astronomy. It was the principal astronomical text passed down by Persian astronomers and eventually inherited by European scholars during the Renaissance.

Most of the Almagest is devoted to scientific measurement, calculation, and predictions of the positions of the Sun, Moon, and visible planets—since these seven objects exhibit the most complex motions within the celestial sphere. But in the first of the thirteen books that make up the volume, Ptolemy laid out the worldview on which his mathematical theory was based, identifying basic principles that seemed to be supported by observational evidence.

In the first six sections, he took for granted that the Earth is at rest, and on this basis argued that the stars must lie on a spherical shell—since this is the only shape that could account for the observed uniform angular arcs of the stars. He then explained that the Earth must also be spherical, and elaborated on Aristotle’s reasons, citing:

- That while lunar eclipses begin and end simultaneously everywhere, the corresponding local times of these events occur later in the east than in the west, with time differences proportional to the distances between locations;

- That the way the celestial poles rise in altitude when travelling north—while stars visible in the south vanish below the horizon—cannot be explained if the Earth were any shape other than a sphere;

- That when sailing toward mountains or other elevated landforms, they appear to rise up out of the sea as if previously submerged—an effect due to the curvature of the water.

He then argued that the spherical Earth must lie at the centre of the celestial sphere. If it were offset, the apparent angular speeds of the stars would vary, and lunar eclipses—when the Moon lies opposite the Sun—would not occur as they do. Next, he explained that the celestial sphere must be so distant that the Earth is essentially point-like by comparison. If this were not so, then the apparent angular speeds of, and distances to, the stars would vary with hour or latitude, which they do not. And the horizon would not always bisect the celestial sphere perfectly, as it consistently does.

Finally, in section seven, Ptolemy addressed the possibility that Earth might itself move. He first rejected the idea that Earth might drift through the celestial sphere, on the same grounds as before: such motion would result in varying distances and angular speeds that are not observed. He then considered a more radical hypothesis—one that had existed for at least six hundred years but had always remained a minority view—that instead of the whole celestial sphere rotating daily, the same phenomena could be explained if the Earth were rotating once per day instead.

Ptolemy acknowledged that there was nothing in the celestial phenomena that ruled this out. If Earth were spinning and the stars were fixed, the sky would look the same. But he argued that the idea was absurd and contradicted all known physics. To him—and to essentially every philosopher and astronomer before him:

- Earth is the heaviest element, and naturally comes to rest when no force is applied. (Throw a rock as hard as you can—it always comes to rest.)

Water is lighter than earth (rivers, lakes, and oceans lie above ground, and rocks sink in them), but it too tends downward.

Air and fire are lighter still and tend to rise.

The cosmos, including the stars and planets, sits above it all. - Even if, for the sake of argument, we grant that the lightest elements are perfectly still—despite the evident motions of clouds, winds, birds, and insects…

- And even if, further, we grant that Earth itself might be in perpetual motion—despite the obvious difficulty of budging heavy boulders, let alone the whole Earth…

- The imagined rotation of the Earth is not slow or modest. It would have to be the most violent motion in existence: Earth, to rotate once per day, would have to be spinning so rapidly to the east that:

- Anything above it—air, clouds, birds, butterflies, arrows—would appear to move rapidly westward;

- Or, if the air were somehow moving with the Earth, then anything launched into it—even a person who jumps into the air—would also move westward upon landing;

- Or, if things somehow “stuck” to the air as we imagine rocks and people stick to the spinning Earth, then nothing would fly through the air at all.

The concept of a “second” did not yet exist in Ptolemy’s time—there was no way to measure such short intervals. But to give a modern sense of scale: for Earth to account for the apparent daily rotation of the sky, and given its 40,000 km circumference, it would have to rotate at roughly 400 m/s at Mediterranean latitudes.

That is—to Ptolemy—if Earth were spinning rather than the stars, then when you jumped off the ground for just one second, unless you somehow became stuck in the air, you’d land 400 metres to the west.

Given the absurdity of this conclusion, he reasoned that Earth must be at rest. And to reconcile that with the apparent rotation of the heavens, the following picture necessarily followed: a sphere of fixed stars rotating once per day around a spherical Earth, motionless at the exact centre, and proportionally so small that it is like a single point at the centre of a sphere.

The Earth, which appears to be motionless—and which would give rise to violent effects if it did move—must therefore be still. And the sphere of stars, which appears to move as one, must truly be rotating.

This was the worldview that most cultures on Earth accepted for millennia. And they arrived at it by piecing together observations of the stars and of earthly motion, considering all possibilities, and identifying a coherent set of principles that accounted for the appearances. They did not rely on qualitative impressions alone, but measured and recorded data, tracked positions and timings, and developed mathematical models that successfully predicted celestial events.

And it should humble us to know that while astronomers like Ptolemy carefully considered the evidence available to them—working with precision instruments, gathering data that spanned centuries, and entertaining alternative hypotheses in order to build a mathematically predictive theory that matched observations—their entire worldview was still wrong in nearly every essential detail.

Reading the Planets’ Shadows

In addition to the uniform, concentric motion of the stars, there is a secondary motion layered onto the celestial sphere: the motion of the Sun, Moon, and five naked-eye planets—Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. All seven objects trace paths near the Sun’s course, called the ecliptic.

Ptolemy first discussed this secondary motion—slower than the daily rotation of the celestial sphere, variable in speed, and mostly in the opposite direction—in the eighth section of Book I. He then devoted the remaining twelve books of the Almagest to developing mathematical models that described it.

Roughly speaking, each planet was modeled as moving along a small circle called an epicycle, whose center in turn travelled along a larger circle called a deferent, with Earth near the center. Each epicycle’s motion was described as uniform—but relative to a particular point called the equant, which was offset from the center of the deferent. The Earth, in turn, was located on the opposite side of the center, at a point called the eccentric.

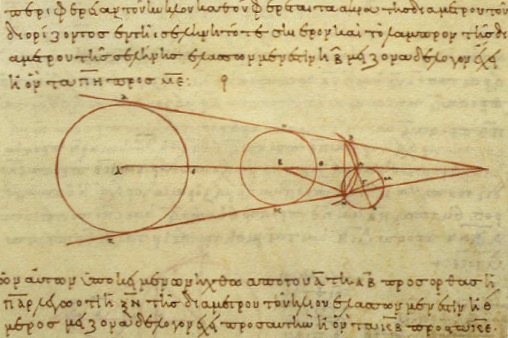

The geometric principle behind the model—that celestial motions must be reducible to uniform circular motion—goes back at least to Plato and Eudoxus, who described the heavens in terms of concentric spheres. By the early second century BCE, Apollonius of Perga had introduced the deferent–epicycle construction, showing its mathematical equivalence to the eccentric circle. Hipparchus then developed these schemes into working models of the Sun, Moon, and planets, employing both epicycles and eccentrics to improve predictive accuracy. Ptolemy’s major innovation was the equant, a point offset from the center of the deferent relative to which the motion of the epicycle was uniform. This device greatly improved the model’s accuracy, but it also violated the very principle of uniform circular motion—and this was the feature that drew Copernicus’s ire 1,400 years later. In De revolutionibus, he described Ptolemy’s model as a “monstrosity,” and proposed a Sun-centered alternative that aligned more closely with Platonic and Aristotelian ideals.

But whatever Copernicus’s philosophical objections, Ptolemy’s model was grounded in reasoned first principles and explained a wide range of phenomena—hallmarks of a good scientific theory.

The combined effects of shifting perspective (by placing Earth at the eccentric), speed and distance variations (enabled by the equant), and the layered motion of each planet’s epicycle orbiting its deferent, allowed Ptolemy to model many subtle observations. These included changes in the Sun and Moon’s distance and speed across the sky, phenomena like Supermoons, and annular or total solar eclipses—explained by the apparent changes in the Sun’s and Moon’s angular size throughout their orbits. The model also accounted for the Sun’s varying speed along the ecliptic: it moves fastest—and appears largest—in January, and slowest—and smallest—in July.

By giving the planets greater speed around their epicycles—as if they were moons orbiting invisible companions several times per orbit around Earth—Ptolemy also explained retrograde motion: the fact that planets occasionally halt in their eastward drift through the stars, loop westward, then resume their course eastward.

All of these phenomena—the Sun and Moon’s varying size and speed, and the retrograde motion of the planets—were, in Ptolemy’s system, explained as real effects. Just as the celestial sphere was taken to rotate daily because it actually did rotate around Earth, so too the planetary motions were treated as physical events. The Sun and Moon actually changed size because they moved closer or farther. They moved through the stars because they really moved relative to them. And the planets’ irregular speeds and retrograde loops were caused by real motion—genuine eastward or westward movement—encoded in a geometric model that described physical relationships, not just predictive rules.

As noted above, Ptolemy was aware that his was not the only proposal. He discussed the earlier, “ridiculous” suggestion that it might be Earth—rather than the heavens—that rotates each day. The most famous version of that idea came from Aristarchus of Samos, a prominent third-century BCE astronomer and a contemporary of Eratosthenes. Aristarchus is remembered for his early estimate of the distance to the Sun, but his most radical proposal was a model in which the spherical Earth rotated daily on its axis and orbited the Sun annually—a framework we now know to be true.

The Shadow Reader’s Epistemic Playbook

Ptolemy’s model was, without a doubt, the most obvious choice of any astronomical framework.

All the physical evidence suggested the Earth was at rest, and that it was in fact ridiculous to think that it could be spinning at several hundred metres per second without any observable consequences. That the Earth might be spinning like this, and yet when an arrow was shot straight into the air it would still appear to fall straight down to the moving Earth rather than appearing to travel several kilometres westward while the Earth rotated beneath it, lacked a reasonable explanation. That the wind likewise would not be constantly blowing to the west at more than a thousand kilometres per hour was similarly unexplained by those who suggested the Earth was rotating.

And on that basis, Ptolemy constructed a celestial model that likewise made sense. According to his model, the celestial sphere appears to rotate overhead once per day because it really does this. The Sun appears to circle through the celestial sphere every year because it does that. The Moon does the same each month because it actually travels around the celestial sphere each month.

The planets—particularly Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, which venture away from the Sun rather than moving back and forth across it—all appear to follow retrograde loops when they’re on the opposite side of the celestial sphere from the Sun because their paths really do loop backwards, their epicyclic retrograde speed temporarily outpacing their deferential speed.

In a qualitative sense, at least, Ptolemy’s model is characterised by a quality that it aimed to describe phenomena as appearing the way they do because the celestial bodies really do move as we see them to be doing.

This is a fair and defensible epistemic approach, even by the most conservative scientific standards.

And while on the surface the Ptolemaic model made a lot of sense, and its predictions were indeed accurate, it was not without its flaws.

In retrospect, the fact that geocentric models required first the eccentric, and then the equant to be incorporated into them, to provide enough flexibility in adjusting speeds and distances, is a red flag. These were not grounded in any physical reasoning, but were merely added to the geocentric picture of deferents and epicycles in order to “save the appearances”—i.e. they were fudge factors, added in to make the model match the detailed measurements.

Furthermore, there was no grand unified clockwork system, with set deferent and epicycle radii or associated eccentrics and equants, in which the whole planetary system could be modelled as one. In fact, the model had to be calibrated to each object individually using recent observations, and then evolved individually into the near future to predict planetary positions.

When modelling the Moon, its position and apparent size could not be modelled with a single set of parameters. To account for the Moon’s changes in speed and position, the Ptolemaic model had to assign it an epicycle so large that, if taken as real, the Moon would swell to much larger than its observed size at closest approach. But to match its actual apparent size changes, a much smaller epicycle would be needed, according to which its speed and position would be inaccurate.

This lack of consistency indicated that while the Ptolemaic model made sense as a framework for explaining the overall features of celestial orbits, as a detailed model it was lacking. The requirement to invent ad hoc parameters like the eccentric and equant, and the inconsistency between parameters needed to fit the model to different data sets should be viewed in retrospect as clear signs of a fundamentally flawed framework.

Insightful, Open-Minded, Courageous Shadow Reading: Six Figures who Revolutionised our Understanding of Reality

I. Aristarchus of Samos

In Johnson’s Rasselas, a philosopher devotes himself to the dream of flight. For months he labours in solitude, eventually crafting a set of wings fashioned after bats. With help from Rasselas and his companions, he hauls this contraption to a nearby height. There, as he prepares to launch himself into the air, he offers a final remark: “Nothing will ever be attempted if all possible objections must first be overcome.” He leaps—and plunges immediately into a lake below.

I like to think this story captures science at its best. We rarely stumble upon fully working models—let alone thoroughly accurate, full-fledged theories—on the first attempt. Usually, like the philosopher in Rasselas, our first attempts are flops. But fear of failure—of not having everything just right—doesn’t deter us from trying. And there can be merit even in complete failures like the one in this example. The design Johnson had in mind isn’t so different from modern hang gliders, which actually do work. And since learning to fly, we’ve gone far beyond merely gliding.

In the story of how we discovered that the Earth isn’t actually at rest at the centre of everything, Aristarchus’s third-century BCE Sun-centred model played a similar role to the philosopher’s bat wings.

Recognising that the retrograde loops of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn always occur at opposition—when the Sun lies on the opposite side of the celestial sphere from those planets—Aristarchus proposed an alternative explanation. A deferent-and-epicycle model doesn’t require loops to occur during this alignment (see the animation above—the Sun is not even in it!), so Aristarchus sought a deeper reason for the coincidence. He showed that if the Sun were instead the centre of planetary motion, and the Earth followed a circular orbit lying outside the orbits of Mercury and Venus but inside the orbits of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn—with inner planets orbiting more quickly than outer ones—then the outer planets would appear to follow retrograde loops whenever Earth passed between them and the Sun. This would happen even if the planets were simply following circular paths.

Thus, the apparent retrograde loops would be an optical illusion caused by parallax shifts—like the shifting of your thumb relative to more distant objects when you hold it in front of your face and wink back and forth. As we travel past the outer planets in our orbit around the Sun, they would appear to shift against the backdrop of the more distant stars.

Aristarchus’s explanation also accounted for why Mars’s retrograde loop is the largest, followed by Jupiter’s and then Saturn’s: Mars is the next planet out from Earth, then Jupiter, then Saturn, and closer objects exhibit greater parallax. (Try holding your hand close to your face and winking back and forth, then slowly pull it away.)

His model also explained why retrograde loops occur less frequently for the more distant planets. Mars, the closest of the outer planets, has a 687-day year, so we catch up to it every 780 days. Jupiter takes twelve years to orbit the Sun, so it comes to opposition every 399 days. Saturn, with a 29.5-year orbit, reaches opposition most frequently, every 378 days.

Aristarchus even estimated the size of the Sun and reasoned that it was the more natural centre of planetary motion. His method involved observing the geometry of the Sun-Earth-Moon system at first-quarter Moon to estimate the relative distances to the Sun and Moon, and determining the Moon’s distance from the geometry and timing of lunar eclipses. From these two values, he estimated that the Sun’s distance was between 400 and 1400 times the radius of the Earth, depending on his measurement of the Moon’s angular size—putting the Sun’s radius between 7 and 27 times that of the Earth.

As long as the celestial sphere was much farther out—so that Earth’s displacement from the precise centre would not produce the perspectival effects Ptolemy described when arguing that Earth must be like a point at the centre—Aristarchus’s model would work. In this case, the celestial sphere would have to be so vast that not only the Earth but its entire orbit would shrink to a point by comparison, ensuring the apparent stellar motions were not disrupted as Earth circled the Sun.

Several decades after Aristarchus made this radical proposal, Archimedes used Eratosthenes’s estimate of Earth’s size and Aristarchus’s estimate of the Sun’s distance to calculate that, even using the most generous values, Aristarchus’s model would preserve stellar appearances if the celestial sphere had a radius of two light years. (Amazingly, the nearest star to us, Proxima Centauri, is 4.2 light years away.)

The details of Aristarchus’s model have turned out to be remarkably accurate. His explanation of the retrograde loops of the outer planets is entirely in line with modern accounts. And from a contemporary perspective, his explanations of why retrograde motion occurs at opposition, why loop sizes vary, and why opposition intervals lengthen with distance, all offer compelling evidence for a heliocentric system.

But in its time, Aristarchus’s model had three very strong marks against it.

First, reconciling Earth’s motion with the appearance that it is not moving was a serious issue. As Ptolemy rightly noted four centuries later, if the celestial sphere rotates daily while Earth remains still, all is well. But if Earth were instead rotating relative to a fixed sky, it would have to spin at several hundred metres per second. And if it orbited the Sun at the distance Aristarchus estimated—refined by Ptolemy to 1210 Earth radii—it would have to move at 1.5 kilometres per second. There was no ancient explanation for how this could be physically possible. So however enticing Aristarchus’s account may have been, the model must have seemed physically untenable.

Second, in terms of practicality, after Hipparchus added the eccentric in the second century BCE and Ptolemy added the equant in the second century CE, the Earth-centred model became highly accurate at predicting planetary positions. In contrast, while Aristarchus’s qualitative explanations were compelling, no mathematically precise, predictive heliocentric model was ever developed in antiquity.

Third, Aristarchus’s model required accepting that the phenomena appear as they do not because the world really is as we see it, but because of optical illusions. The Earth appears to be at rest while the sky turns overhead—but Aristarchus claimed it’s actually the other way around. The Sun appears to circle through the zodiac constellations—but in his model it’s Earth that moves, and the Sun only appears to shift against the distant stars. The retrograde loops of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn appear to trace real paths—but Aristarchus explained them as parallax effects.

This last point is no trivial matter. We cave dwellers have consistently preferred to believe that the shadows are all there is—that there is no fire behind us, no cats and dogs casting shadows on the wall. And Ptolemy’s model described all of these motions as happening because they actually happen. The sky appears to rotate because it does. The Sun appears to circle the zodiac because it really moves along the ecliptic. The planets trace retrograde loops because they really do that. It’s the simplest, most literal reading of the phenomena. And it took no imagination at all to believe it was true.

To accept that the Sun is actually at the centre of planetary motion would require confronting all three of these challenges. The first serious attempt to do so would come 1400 years after Ptolemy—and 1800 years after Aristarchus first proposed his radical, imaginative, and fundamentally correct explanation.

II. Nicholaus Copernicus

In 1818, Mary Shelley introduced the world to a new kind of monster—a being assembled from pieces of other humans, reanimated into tragic life. While the Creature was fully human inside and out, its body, stitched together from disparate parts, was so grotesque that it would never be treated as human. Its monstrosity wasn’t the result of what it was made of, but how it was made: a single figure cobbled from mismatched anatomical fragments, held together only in outward form.

Frankenstein’s monster is now iconic—but it wasn’t the first of its kind.

The earliest known reference to this idea—a human form composed of mismatched parts—comes not from literature or myth, but from science. In 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus used the image as a metaphor in his preface to his major work, De Revolutionibus, addressing Pope Paul III. Reflecting on the state of astronomy before his own work, he described the Ptolemaic system as:

“Just like someone taking from various places hands, feet, a head, and other pieces—very well depicted, it may be, but not for the representation of a single person; since these fragments would not belong to one another at all, a monster rather than a man would be put together from them.”

What troubled Copernicus wasn’t their appearance—“very well depicted,” as he said—but that they came from incompatible sources, grounded in conflicting assumptions. Some omitted essential pieces; others included extraneous or irrelevant ones—stitched together only to save appearances. The result was not a coherent explanation of the cosmos, but a grotesque contraption—technically functional, but fundamentally malformed.

Copernicus gave his reasoning more specifically in the Commentariolus, a short document he circulated among friends in 1512. There, he offered his main criticism as being that geocentric models had only attained sufficient numerical precision through Ptolemy’s introduction of the equant, through which “a planet moved with uniform velocity neither on its deferent nor about the centre of its epicycle,” which seemed to him “neither sufficiently absolute nor sufficiently pleasing to the mind.” He therefore sought “a more reasonable arrangement of circles… in which everything would move uniformly, as a system of absolute motion requires.”

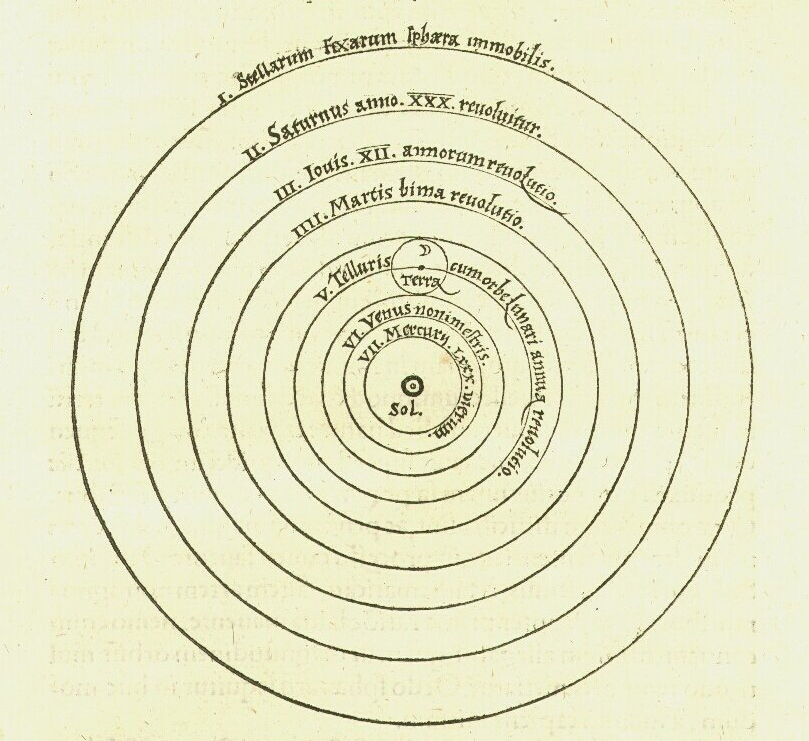

In other words, Copernicus’s main objection to Ptolemy’s model was that it violated the Aristotelian principle of uniform motion. His aim was to find a different framework that could restore that ancient principle. In the process, he became the first person in 1800 years to put forward a serious proposal for a theory that placed the Sun at the centre of planetary motion, including the Earth as the third planet from the Sun.

There has been a lot of speculation over the years about whether Copernicus was aware of Aristarchus’s theory, since he didn’t note, either in the Commentariolus or De Revolutionibus, that Aristarchus had made the same proposal in Antiquity. Several eminent historians of science and Copernican scholars have argued that he did not, that his was an independent proposal. I’m convinced they’re wrong: Copernicus most certainly knew of Aristarchus’s theory and didn’t credit him. Since this claim—that Copernicus was as aware as any modern scholar of the details of Aristarchus’s theory—is outside the scope of the current essay, I’ve written a follow-up essay that makes the case.

For our purposes here, the goal is to explain what Copernicus did to advance the theory and overcome the three obstacles noted above.

On the first point—justifying the claim that Earth is actually moving and yet does not appear to be—Copernicus made little progress. He did argue that projectiles launched from Earth should move with it, and noted that this is observed on a ship when the sea is calm. But his points weren’t novel—Oresme had made the same argument a century earlier—and his explanation remained imprecise and incomplete.

The second obstacle is where Copernicus made the greatest advance. While his model was incorrect on several significant details, he did manage to produce a model that could predict celestial motions as accurately as Ptolemy’s.

This model was still Aristotelian—and arguably more so—as he had successfully restored the principle of uniform circular motion. The planets all revolved around the Sun within crystalline spheres, moving at constant speed along circular paths. At the centre, Copernicus replaced a stationary Earth with an equally stationary Sun. And at the furthest extent, he placed all the stars around a two-dimensional sphere, keeping them at fixed positions.

Copernicus attributed the daily rotation of the stars to Earth’s own daily spin, and the Sun’s apparent annual motion through the ecliptic to Earth’s yearly orbit—viewed from a frame in which Earth appears at rest. These points, as well as the explanation of the planets’ retrograde motions, he took from Aristarchus.

Just as Ptolemy noted that the stellar sphere’s uniform motions are due to Earth’s radius being negligible compared to its size, Copernicus argued that the same observational evidence could be preserved in a heliocentric system, so long as Earth’s orbit is likewise insignificant relative to the distance to the stars.

Finally, regarding the third obstacle—interpreting the apparent motions as illusions caused by our own motion—Copernicus made no conceptual advances beyond Aristarchus. But his demonstration that the model produced results just as accurate as Ptolemy’s went a long way toward convincing others that the illusion argument could be taken seriously.

For all its imperfections, Copernicus’s achievement was monumental. He didn’t just imagine a better system—he committed to it. He fished Aristarchus’s bat wings out of the lake, took them back to his workshop, and spent decades refining them. When he finally jumped, his model spiraled and fluttered—it didn’t soar—but it cleared the bank and landed softly in the water. And that changed everything.

Or, to borrow his own metaphor, he gave birth to a coherent human form in place of a monster. It was an odd-looking human to eyes that had only ever known monsters, stitched together from centuries of epicycles and fudge-factors—to people who still desired what the monster stood for. But within a generation, this new being found defenders who nurtured it, refined it, and gradually turned it into something far stronger. The human could grow. The monster could not.

III. Thomas Digges

If Copernicus weakened the celestial shell, it was Thomas Digges who burst through it.

In 1576, just three decades after De Revolutionibus was first published, Digges released an English translation of key portions of Copernicus’s work. But he did more than translate. He expanded. In his commentary, Digges introduced a bold new conception of the cosmos—one that went far beyond what Copernicus himself had dared to claim.

Copernicus had retained the old framework of a spherical stellar shell: even though Earth orbited a stationary Sun which was surrounded by fixed stars, the stars were still placed within a shell beyond Saturn. Digges rejected this last relic of antiquity. In its place, he imagined the stars as scattered throughout boundless space—no longer fixed to a spherical shell but distributed at varying distances throughout an infinite cosmos. The celestial sphere was no longer the outermost wall of a nested universe; it was an illusion, a projection onto our apparent sky, born of perspective.

He even drew it: the first published diagram in history to depict the stars not on a shared surface, but dispersed outward, fading into infinity.

This was not a minor adjustment. It represented a shift in metaphysics as well as astronomy. For the first time, the cosmos could be conceived not as a system of layered, concentric spheres, but as a three-dimensional expanse without edge or center. Digges had not just embraced heliocentrism—he had reimagined the structure of space itself.

And the key to this transformation lay in a single conceptual move: the recognition that observed celestial motion could be a projection, not a property. The daily sweep of the stars and the Sun’s yearly path were not real motions through space, but artifacts of Earth’s own rotation and orbit—observed from a moving vantage point. The stellar sphere, so long treated as a literal wall of heaven, dissolved into depth.

It was, in a real sense, the beginning of cosmology as we know it.

Digges did not cloak these ideas in mysticism. He presented them as natural extensions of Copernican reasoning, made accessible to craftsmen, mechanics, and readers of English. And in doing so, he shifted the discourse decisively—from philosophical speculation to physical structure, from celestial metaphor to scientific model.

If Plato’s allegory warned us not to mistake the shadows for reality, Digges showed how to turn around—how to see that the rotating celestial sphere might be a shadow cast by our own motion. In this, more than any of his contemporaries, he quietly launched the conceptual revolution that would make Newton possible.

And in England, at least, he did more than launch it—he normalized it. For nearly a century, Digges’s version of Copernicanism was the version that circulated in English, long before telescopic evidence or Newtonian mechanics could vindicate it. His rendering helped shape the cultural and theological preconditions for England’s later embrace of an infinite, law-governed cosmos.

IV. Galileo Galilei

Aristarchus and Copernicus had constructed models that explained celestial phenomena on the assumption that Earth was moving. Digges went further still—reimagining the very structure of the cosmos as unbounded and filled with stars.

Galileo brought that vision into focus—through the lens of a telescope.

He was the first to offer direct observational evidence that the heavens are made of matter. The Moon, he saw, was mountainous—scarred like Earth. Jupiter had moons of its own. Venus exhibited a full set of phases as it orbited the Sun. The Milky Way resolved into a sea of stars—countless, unreachable. The Sun itself was marked with sunspots: rotating, active, unstable.

He also proved, through experiment and insight, that gravitational acceleration is independent of mass; that bodies in motion remain so unless acted upon; and that from any locally inertial perspective, the world behaves as if it is at rest.

Where Aristarchus, Copernicus, and Digges had shown that the observed phenomena could be accounted for if Earth were moving, Galileo dismantled every reason to think that Earth could not be moving. He showed that a moving Earth was not only conceivable, but dynamically consistent.

Today, his achievements are widely recognized. But in his lifetime, the frustration he felt at others’ inability to see what he saw is palpable.

He observed the Moon’s terrain and saw that it was no perfect sphere—just another world. If such a massive, Earth-like body could orbit Earth, why could not Earth itself move?

He studied Jupiter and Saturn and saw that they were not points of light but disks. Saturn had “ears,” and beside Jupiter were four bright points in a line—moons, visibly orbiting.

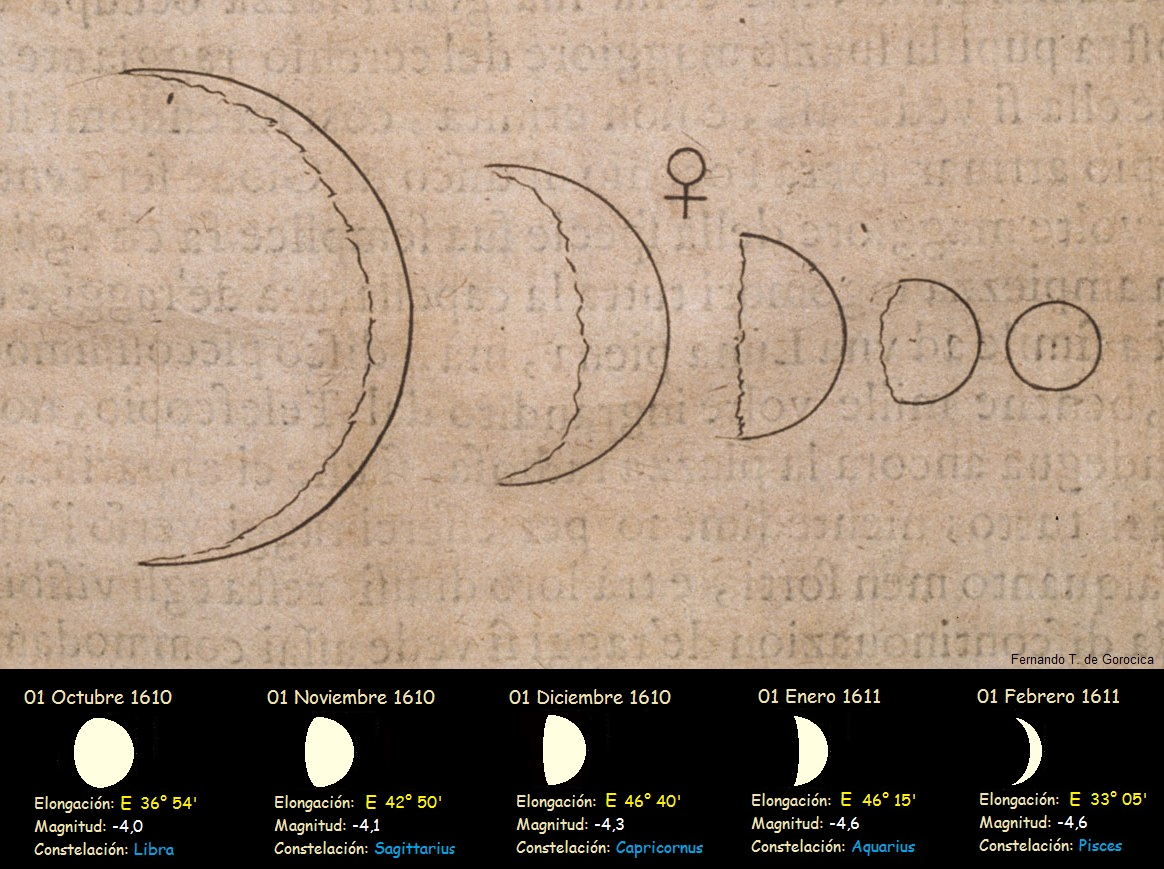

He watched Venus wax and wane in a full cycle of phases, proving that it orbits the Sun.

These observations—of Venus, and the moons of Jupiter—disproved the idea that Earth is the center of all motion in the universe.

Galileo damaged his eyesight observing sunspots: dark regions that rotated, grew, and faded. The Sun, he saw, was not immutable.

He gave telescopes to others, showed them what he had seen. But many refused to believe. Some said they could not see it. Others claimed the images were distortions.

If you’ve ever tried using a cheap telescope—or tried teaching someone else how to—you’ll understand that this was not mere stubbornness. And Galileo’s instruments, even compared to the worst telescopes today, had abysmal optics and a tiny field of view.

And if you’ve ever tried to persuade someone to abandon their deepest beliefs—or had someone try to do the same to you—you’ll understand why Galileo’s claims, however carefully argued, were dismissed. What he saw upended their entire worldview. Their resistance was not just stubbornness—it was human nature.

In addition to the observational evidence, which was easy to dismiss, his explanation of the phenomena was more abstract than the standard theory. In keeping with Copernicus, he explained that the apparent motions of the Sun, stars, and planets were illusions—created by Earth’s own motion through space. That the Earth’s daily spin explains the apparent rotation of the sky. That its annual orbit accounts for the Sun’s apparent path through the zodiac. That the retrograde paths of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn are projections—epicycles dissolved by perspective, in a model that still required epicycles to account for other phenomena.

Even so, Galileo showed that Aristotle’s physics was wrong: heavier objects do not fall faster than lighter ones. Everything falls at the same rate, unless altered by air resistance. The Earth’s incredible mass gave it no special place—no anchor at the bottom of the cosmos.

He dismantled, one by one, the reasons to believe that Earth must be fixed and central. And the frustration of being right and dismissed—of seeing clearly what others would not see—must have worn on him. But he was not done.

When he prepared his masterwork, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, he was given strict instructions by the Church: he had permission to present the Copernican model only hypothetically, and he must include Pope Urban VIII’s argument—that God, being omnipotent, could have arranged the universe in any way, and we have no right to say it must be one way and not another.

But Galileo could not help himself. Most famously, in this book he gave an unmistakably clear explanation of the fact that an object moving at constant speed will continue that way unless acted upon by an external force—and that there could be no means of differentiating, through local experiment, between such inertial motion and actual, absolute rest.

He accomplished this by situating the reader in the cabin of a ship moving along a calm sea at constant speed. There could be no wind resistance—so he explained that under these conditions, butterflies would fly freely in all directions rather than being pinned against the back wall; that water dropping from a table would fall straight down; that a person who jumps straight up would land straight down; and that they’d be capable of leaping forward just as easily as backward.

We experience the same today when driving along the highway, or on a train or plane that has reached cruising speed. When accelerating, we feel a force that pushes us back in our chairs; when cruising, it’s as if we are perfectly at rest. We can throw a ball up, and it will come back down—rather than hitting us in the chest.

In a plane cruising at 500 miles per hour, a major-league pitcher can still throw a ball forward at 100 miles per hour. It doesn’t fly backward at 400—it travels forward as expected, relative to him and the cabin. Any person can throw a ball with the same speed whether toward the front or the back of the plane.

This simple thought experiment shattered a long-standing argument—repeated from Aristotle and Ptolemy through to Galileo’s time—that if Earth were rapidly spinning, and if it were orbiting the Sun at even greater speed, then winds would howl, and birds could not fly eastward. We would feel and see this motion.

But none of these things happen—because the air, the birds, the projectiles, and the people all have the same inertia as the spinning and orbiting Earth.

Galileo’s argument for a moving Earth was clear. And while he included the contrasting geocentric view, in his dialogue he placed it in the mouth of Simplicio—the “simpleton.” And it was Simplicio who, near the end of the dialogue, presented Urban’s favored argument.

Galileo let his frustration get the better of him. And Urban, once an ally, became his judge.

The Inquisition summoned him. Under threat of torture, he was forced to recant. Legend has it that afterward he defiantly declared, E pur si muove—“And yet it moves.”

Galileo spent the rest of his life under house arrest, forbidden to teach or write about the motion of the Earth.

And yet, in that very book, he had already planted the seeds of the next revolution—showing not only that Earth moves, but that the laws of motion themselves are indifferent to the choice of rest or motion. What matters is relative motion, not absolute position. Galileo laid the foundations of a physics that would, a generation later, become Newtonian mechanics.

He was silenced—but not extinguished. The silence did not last.

Of the three ancient obstacles to accepting Aristarchus’s model, two had now been overcome. Copernicus had developed a Sun-centred model that rivalled Ptolemy’s in accuracy. Galileo had shown, with elegant clarity, that if Earth were moving, its motion should go completely undetected.

And together, they had weakened the third and deepest objection: the belief that reality should present itself to us directly—that if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck. In fact, between them, they had shown that every apparent phenomenon must be carefully deconvolved—separating real motions, like the Moon’s orbit, from those that might be purely perspectival, like the Sun’s apparent orbit around the celestial sphere.

They had shown that it is the scientist’s responsibility to disentangle these things—to explain which appearances are literal translations of reality, and which are illusions, giving clear reasons why the illusions should present as such.

An objective judge would now favour neither model over the other.But to complete the revolution—to make a convincing case that Earth actually is a planet orbiting the Sun—the heliocentric model had to do more than match Ptolemy. It had to outperform it. And the person who made that happen was Johannes Kepler.

V. Johannes Kepler

Kepler was a tenacious crank. From a young age, he was seized by what he took to be a vision of cosmic perfection and harmony, and it guided his efforts for the rest of his life.

He believed that with the Sun at the centre of motion of the six known planets (including Earth), God must have arranged their orbits by placing the five Platonic solids between them—each one nested perfectly between two planetary spheres. The centre of each face rested against the inner planet’s sphere, and the outer sphere aligned with the vertices of the Platonic form. It was an elegant geometry, a beautifully harmonious world—one that Kepler believed was Divinely tuned to literally sing.

And it was completely wrong.

But what mattered is what Kepler did with it. He toiled obsessively, searching for a model that would fit both the data and his conviction that the solar system had been designed as a perfect harmony of perfect shapes.

He moved to Prague as the assistant of Royal Astronomer Tycho Brahe. Upon Tycho’s untimely death, and Kepler’s serendipitous promotion to the role, he gained full access to the most accurate planetary dataset in existence. He spent years struggling to reconcile Tycho’s data with different models, feverishly calculating for months—or even years—each time a new and exciting idea struck him. He tried equants, epicycles, and off-centre orbits, reintroducing the very mechanisms that had led Copernicus to abandon geocentrism. He also tried oval and egg-shaped paths. He adjusted and readjusted his models more than seventy times.

Each time, after working through the calculations and testing a finely tuned model against the data, if it failed to match within observational accuracy, he scrapped the entire thing. And within a day or two, a new and even more beautiful idea would strike him.

In working with the data, he noticed that when a planet was further from the Sun, it moved more slowly—and sped up when it came closer. He suspected the Sun was guiding the orbits somehow, and speculated it might be through a magnetic force. He looked for a relationship to describe the changing speed, noting that a line between the Sun and planet swept out a larger area when the planet was farther away, but took longer due to its slower speed. He guessed that the area swept out in equal time intervals might be constant, and tested this using an equation that could account for the curve of the orbit.

It worked. Kepler discovered that a line between each planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal time intervals. He then examined the equation more carefully and realized it described an ellipse, with the Sun located at one focus.

Kepler’s first discovery is what came to be known as his Second Law, and the second discovery is called his First Law.

A decade later, still fumbling through numerological speculations while hunting for empirical relationships in the data, he discovered his Third Law: the square of the period of each planet’s orbit (measured in years) is equal to the cube of its distance from the Sun (when expressed as a fraction of the Earth–Sun distance); i.e. P2 = a3.

These three laws were not metaphysical revelations. They weren’t ontological claims. They didn’t explain why the planets moved the way they did. But they were true—empirical relations grounded purely in observational data and simple geometric structures, projected onto the sky through complex mathematical mappings.

They worked.

They were empirically precise, mathematically crisp—and philosophically devastating. They undermined the circles, epicycles, and equants that had dominated astronomy for two thousand years.

None of it looked right. But it was right.

With these three laws, Kepler outperformed Ptolemy. He shattered the ideal of uniform circular motion that Copernicus had reinstated with such care. And he prepared the scaffolding that would allow Newton to reimagine the entire edifice.

What Kepler did was epistemically extraordinary. He started with sacred geometry, much like those who came before him—and he watched it crash, over and over. But each time, he learned from the crash. He fished the wings out of the lake, studied their failure, reworked and retooled them based on what his previous attempts had taught him—until finally, he built something that could fly.

They weren’t the wings he’d imagined. But they flew all the same. And when they did, he accepted the design that worked over the one he had wanted to work.

That act of surrender was the revolution.

The illusion cracked. The planets were not attached to perfect spheres. They did not orbit in circles. The music of the heavens was gone.

VI. Isaac Newton

In the century leading up to Newton’s birth, the common worldview was transformed. The idea that the cosmos was made of ethereal crystalline shells spinning overhead—daily, monthly, annually, and so on—all finite, bounded, and turning like spherical clockwork—had been replaced by something radically different.

In 1627, Kepler finally completed and published the Rudolphine Tables, offering extremely precise predictions of planetary positions using elliptical orbits. The first major confirmation came in 1631, when Pierre Gassendi observed the predicted transit of Mercury—marking the first successful empirical test of Kepler’s new planetary theory.

By the end of the decade, Kepler’s tables were not merely in use but were being actively refined through improved instrumentation and telescopic observations. In 1639, Jeremiah Horrocks used his own observations of Venus to correct Kepler’s prediction of a near miss: he forecast a visible transit instead, observed it successfully, and used it to estimate that the Sun was more than ten times farther away than Ptolemy had calculated—applying Aristarchus’s method.

In the 1640s, around the time of Newton’s birth, Johannes Hevelius—working in Danzig with a 45-metre focal length telescope—initiated the field of lunar topography with detailed maps of the Moon’s surface and discovered the Moon’s libration. His sunspot observations, far more detailed than Galileo’s, revealed the Sun’s approximate 27-day rotation period by tracking spot shape, persistence, and motion.

In the 1650s, Christiaan Huygens discovered Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, and explained that Saturn’s “ears” were actually a flat, tilted ring surrounding the planet. He also observed surface features on Mars, accurately deducing its rotation period to be approximately 24 hours—much like Earth’s.

In the 1660s and ’70s, during Newton’s young adult years, Giovanni Cassini discovered Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, interpreted its belts as atmospheric bands, determined its rotation period (about 10 hours), discovered two more moons of Saturn, and identified the major gap in Saturn’s rings now known as the Cassini Division.

There was, understandably, considerable uncertainty and debate—but gradually, over the course of decades, the cosmos was terrestrialised: the Moon became a world with mountains, shadows, and maps; the Sun became active, dynamic, and rotating; the planets gained spin, along with moons and complex surface or atmospheric features; the stars became innumerable and distant; and the firmament dissolved into a three-dimensional distribution of worlds—just as Thomas Digges had envisioned following Copernicus’s proposal, nearly half a century before the telescope was invented. That vision, circulating in English since 1576, may well have helped prepare the conceptual ground for England’s early and enthusiastic reception of the Newtonian cosmos.

Newton therefore inherited a Sun-centred planetary model that accurately fit observed motion; an unbounded cosmology in which stars were at different distances and made of matter like the Earth and Moon; and a physical world in which inertial matter didn’t grind to a halt unless acted upon, and otherwise kept moving—even if it appeared to be at rest.

Newton had begun studying the problem of celestial motion as early as the 1660s, in his early twenties. But the focused effort that would lead to the Principia began two decades later, triggered by a visit from Edmond Halley in 1684. Halley asked what kind of orbit would result from a force that diminished with the square of the distance. Newton immediately replied: “An ellipse”—but added that he had misplaced the proof. Halley urged him to re-derive it. Newton soon followed up with a short manuscript providing the derivation, which became the seed for Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica—the Principia—first published in 1687 and funded by Halley.

The Principia was, in essence, a rigorous, systematic demonstration that all motion—planetary, cometary, tidal, and terrestrial—could be explained by a single, universal law of gravitation. This gravitational force, acting at a distance, applied equally to apples falling from trees and moons orbiting planets. In the preface to Book III, Newton explains that while Book I constructs the mathematical foundations and derives the consequences of the laws of motion, and Book II addresses motions in resisting media, the true purpose of the treatise culminates in Book III: to show that the universal law of gravitation is not merely consistent with observation, but uniquely capable of explaining the system of the world.

Book I lays out the general principles: the Definitions, the three Laws of Motion, and the mathematical derivation of Kepler’s laws from an inverse-square force law. Beyond Section III, however, the remainder of the book explores idealized propositions and corollaries that, while mathematically illuminating, are not strictly necessary for understanding the physical world. Book II, often misunderstood, is not a detour but a strategic rejection of Cartesian vortex theory—Newton’s clearest rebuttal to the prevailing belief in a plenum and contact-based mechanisms of motion. Its fluid-mechanical demonstrations serve to eliminate Descartes’s metaphysical scaffolding as empirically untenable. With those distractions cleared away, Book III presents the main event: a concise, mathematically grounded, and empirically supported account of the real world. And Newton makes his pedagogical stance plain: future students should focus on the essential tools—Definitions, Laws, and the first three sections of Book I—and proceed directly to Book III, where the true physics begins.

On this reading, Newton’s theory is more than simply a brilliant synthesis of the best and most accurate elements passed down by Digges, Galileo, Kepler, Descartes, and others. Standing on the shoulders of these giants, as Newton so eloquently put it, he indeed saw further than anyone who came before. Astronomers had by then thoroughly confirmed the accuracy of Kepler’s laws in describing observed celestial motion. Newton derived Kepler’s laws as necessary consequences of an inverse-square central force under his new dynamical framework—transforming Kepler’s empirical fits into physical theorems. But it also explained that, if one were able to climb a tall mountain and launch a cannonball fast enough horizontally, it could continually fall toward the Earth due to this same gravitational force at precisely the same rate that the spherical Earth curves away beneath it—maintaining a constant separation in the circular idealization.

Whereas Galileo had previously imagined inertial motion as curving circularly at great distances—hoping to explain the appearance of being at rest on Earth, along with the natural orbital motion of the planets—Newton refined and clarified Descartes’s notion of inertia, formulating his First Law as a clean, geometrically grounded principle: that a body continues in uniform motion in a straight line unless acted upon by a force. Therefore, he knew orbital motion had to be motion under a centrally directed force, and he arrived at this elegant and intuitive insight: that circular orbits maintain constant separation because the object’s forward speed is perfectly balanced by the inward pull of gravity. If they moved more slowly at the same distance, they would spiral inward, falling toward the central mass; and if they moved more quickly, they would spiral outward, eventually approaching a constant speed in a straight line under weakening gravity.

While Newton didn’t develop the concept of angular momentum, his laws laid the groundwork for later dynamical explanations of solar system formation as we currently understand it. The proto-solar nebula contracted and rotated more and more rapidly as it did—like a figure skater who draws their arms in to spin faster due to conservation of angular momentum. Then, following Newton’s conception of orbital motion, individual particles that were spinning too slowly fell toward the center, while those moving too quickly moved outward. The matter moving at just the right speeds clumped together to eventually form planets, with the majority of mass either falling to the center where the Sun formed or escaping outward to the frozen Oort cloud.

Newton’s theory also explained why we are not flung off the surface of the Earth even though our rotational motion is not purely inertial—and why we don’t feel any effects of this non-inertial motion but experience a world that seems still. While inertial motion is linear according to Newton’s First Law, we are bound to the Earth and follow circular paths as it rotates daily because Earth’s gravity holds us to its surface. Our motion parallel to Earth’s surface at any moment is inertial, but we wouldn’t remain stuck to the surface without the gravitational force.

Newton’s theory explains that at the altitude of the International Space Station, gravitational acceleration is 88% of what it is on the surface of the Earth. And it explains that astronauts aboard the ISS don’t feel that gravitational force—that they experience a sense of weightlessness—because they are in fact orbiting the Earth: constantly falling toward it along with the space station. Their sense of weightlessness is therefore the same as it would be if the ISS were not orbiting but falling straight down toward the Earth with them inside. In that case, too, they would not accelerate relative to the walls of the space station or notice any difference while falling.

Book III confirms heliocentrism not by assumption, but by showing that the same gravitational principles governing Earth’s surface phenomena also govern the motions of the Moon, the planets, and their satellites. Newton demonstrated that the orbits of Jupiter’s and Saturn’s moons follow the same inverse-square law as the planets, and from these dynamics he could deduce relative planetary masses. He also offered the first quantitative explanation of tides as a result of the Moon’s and Sun’s differential gravitational forces—unifying terrestrial and celestial mechanics within a single theoretical framework.

The Scientific Revolution

Newton’s theory was not immediately accepted. While he wasn’t burned at the stake or even forced into house arrest, his proposed explanation of the apparent phenomena in the Principia did face its share of critics.

The mathematical theory was rigorously constructed, and its derived consequences gave remarkably precise descriptions of observations. But the idea of a gravitational force acting at a distance—a force requiring no intermediary contact—was viewed with deep suspicion.

The hypothesis of such a universal force served as an explanation for a wide variety of phenomena. It accounted for all observed celestial motions by showing that Earth is one of six planets, spinning on its axis and orbiting the centre of mass of the Solar System near the Sun. It reinterpreted the celestial sphere as a projection of the positions of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars. It explained that the apparent daily rotation of the heavens was due to Earth’s own rotation. And it showed how the apparent motions of the planets relative to the distant stars, including retrograde motion, arose from a combination of their real motions and our own.

Newton’s theory untangled this complex system of appearances, classifying some features—the daily rotation of the stars, the Sun’s yearly motion through the zodiac, and retrograde motion—as illusions due to perspective, while identifying others—the orbits of the Moon and planets, and the motions of Jupiter’s and Saturn’s satellites—as real. And it explained all these real motions as consequences of inertia and a universal force of gravity.

Still, Newton’s critics pressed for the cause of this gravitational force. His theory described how it worked and what it predicted, but it did not say why it existed. And many were uneasy with the notion that a force could act across empty space with no visible mechanism.

Newton stood firm. His gravitational law explained a vast array of phenomena through a single, quantitatively precise principle, and that, he believed, was enough. He insisted on a sharp distinction between theoretical structures that are derived from phenomena, inferring basic causes inductively from the phenomena and testing those inferences against empirical constraint, and speculative conjectures unconstrained by observation. What he rejected was not theorizing per se, but the temptation to indulge in causal storytelling disconnected from empirical grounds. The law of universal gravitation, in his framework, was no speculation: it was a generalisation of observed regularities, confirmed by its power to explain and predict. What lay behind it—what deeper cause gave rise to its effect—was something he refused to guess at, as there were no known phenomena to guide such speculation.

In two subsequent editions of the Principia, issued in 1713 and 1726, Newton explained his philosophical stance through an opening section to Book III, titled Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy, and a General Scholium he added at the end. The General Scholium gave the argument above, including Newton’s famous hypotheses non fingo declaration—a refusal to speculate about the basic cause of the “power of gravity” due to a lack of observational evidence to guide such speculation.

And in the Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy section at the start of the Book, Newton laid out four principles meant to guide empirical science. The first called for ontological parsimony—admitting no more causes than are both true and sufficient to explain appearances. The second demanded causal unification—assigning the same causes to the same effects, wherever possible. The third projected universal qualities inferred from experiment, asserting that any property found in all observable bodies should be attributed to all bodies whatsoever. The fourth emphasized provisional confidence in empirically grounded generalizations, stating that propositions established by induction from phenomena should be held as true, or nearly so, even in the face of speculative alternatives, unless and until new phenomena demand revision.

These rules were not designed as a general framework for comparing competing theories. They were formulated in the context of defending Newton’s own: the law of universal gravitation. His concern was not with theory choice between paradigms, but with protecting empirical generalization from the erosion of unfounded speculation. For Newton, the central issue was not how to decide between rival systems—Ptolemaic or Copernican, Cartesian or Keplerian—but how to justify the acceptance of a single, empirically derived principle in the absence of a known mechanical cause. And while the four rules gave enduring voice to a rigorous empirical sensibility, they failed to capture the broader philosophical programme that led from Aristotle to Newton, through the great works of Aristarchus, Ptolemy, Copernicus, Digges, Galileo, and Kepler. In this respect, Newton distilled the epistemology of his own discovery—not a general method for the evolving structure of science itself.

But what Newton had also accomplished, which even he may not have fully appreciated, was to finally lay waste to all three obstacles discussed above that had kept Aristarchus’s theory from being accepted, or even carried forward as a serious proposal, in Ancient times.

It was Newton who finally, completely explained that while Earth rotates daily and orbits the Sun annually, we should not expect to sense anything at all from that motion. Where Galileo had shown the way, Newton added crucial insight that corrected Galileo’s brilliant, but flawed reasoning.

It was Newton who finally, completely explained why all the celestial motions should be observed as they are within a heliocentric system. Aristarchus and Copernicus had already drawn the qualitative connection between apparent motion and the Sun-centred system with Earth as the third planet. Copernicus had produced a detailed model that rivalled Ptolemy in terms of accuracy. Kepler had produced a far more accurate model whose predictions were highly accurate, and limited mainly by the precision of data used to constrain specific orbits—which increasingly powerful telescopes had tightened considerably. But Newton explained why everything from falling apples to all the complex planetary motions should appear as they do, according to a single governing law of universal gravitation.

And perhaps most importantly, Newton established once and for all that science should never favour a literal reading of the phenomena over one that explains that what we see is a projection, and that our perspectival view of that projection can be, and often is, misleading.

Plato understood this so well that he devised a simple allegory—one that has stood for 2400 years as a cautionary tale. Aristarchus was the first to apply this reasoning to an explanation of astronomical phenomena, while Copernicus revived that argument. Digges went further still in his novel realisation that the fixed stars in Copernicus’s model need not be distributed across a 2-dimensional sphere, but could extend outwards through a potentially infinite universe. Galileo gave a brilliant explanation of the illusion of rest on a rapidly moving Earth.

And Newton finally laid waste to the notion that “saving the appearances” is enough, through his explanation that all these people had been fundamentally right, and that the operationalists, following Ptolemy, had been wrong to take the simple, literal explanation for granted and build a patchwork monster on that basis. Newton’s theory proved incontrovertibly that uncritically assuming the phenomena directly represent underlying reality is a deep epistemic flaw.

What Newton’s theory showed, in the way it finalised a debate that had simmered over millennia, was that it is the physicist’s responsibility to deconvolve the basic causes of apparent phenomena and produce a description of reality that explains why phenomena should appear to us as they do, and not take them as direct indicators of the underlying structure that casts the shadows.

Rules of Reasoning in Science

The story we’ve traced—from Plato’s cave to Newton’s Principia—is not just a history of astronomy or physics. It’s a history of learning how to reason about the world when our perspective misleads us. Again and again, we’ve seen the same pattern: the appearances suggest one thing, but deeper inquiry—grounded in logic, geometry, and critical observation—reveals that reality must be something else entirely. And each time, it takes courage to say so.

Plato gave us the allegory. Aristarchus made it literal. Copernicus revived it. Digges extended it. Galileo sharpened it. Kepler systematized it. And Newton proved it. Together, they forged the first and most important methodological lesson in the history of science:

Don’t take the appearances at face value.

Ask what kind of world must exist for those appearances to arise.

This is the rule that underlies all of Newton’s own: ontological parsimony, causal unification, empirical generalization, and provisional confidence in theory are all second-order principles derived from a more foundational imperative—to resist being fooled by the immediacy of experience, and instead search for the underlying structure that casts the shadows we see.

That’s why Newton’s law of universal gravitation was not just a brilliant synthesis of terrestrial and celestial mechanics. It was the capstone of a two-thousand-year transformation in our understanding of what science is. Newton did not merely replace one model of motion with another. He formalized a new standard of explanation: one that interprets the phenomena not as raw data to be fit, but as projections of a deeper structure whose logic can be uncovered. He rejected “saving the appearances” as a sufficient goal. The task of science is not to simulate what we see. It is to explain why what we see appears the way it does—even if that requires us to reject what seems obvious.

This insight was hard-won. Before Newton, no one had fully solved the puzzle that Plato laid out. Copernicus made the Sun the center of the cosmos—but left the stars in a fixed shell. Kepler broke the spheres and gave us ellipses—but didn’t explain the cause. Galileo gave us inertia—but misunderstood orbital motion. Descartes gave us a mechanism—but one grounded in metaphysical contact and vortices. Newton, standing on all their shoulders, made the decisive move: he showed that the true world can only be inferred by de-projecting what we see, not by assuming that we see it directly.

And this is the irony we now face. For all the scientific and philosophical progress that Newton made possible, the lesson his theory taught has, in some areas, been forgotten. Modern physics once again celebrates models that fit appearances without accounting for what those appearances mean. Worse: it often confuses the map for the territory, the model for the world, the projection for the structure.

Nowhere is this more evident than in today’s discourse around space-time. We speak of four-dimensional universes, of block worlds in which all moments exist equally. We talk of traveling through time as if it were a landscape, of warping geometry as if the coordinates themselves were real. But this is exactly the kind of mistake Newton—and Plato before him—taught us never to make.

This is not physics.

It is philosophy done badly.

It is metaphysics masquerading as science—bad philosophy, done in the service of sensationalism.

The map of a system is not the system itself. Coordinates are not things. Apparent symmetries are not ontological facts. What we see—or calculate—is always a function of how we view it. The real work of science lies in seeing past the appearance, not mistaking it for reality.To recover the true spirit of science—the one Newton embodied, and that all great astronomers before him groped toward—we must reclaim the rule of reasoning that made modern science possible in the first place. We must remember that what we see is not always what is. We must resist the temptation to reify our coordinate systems, and instead ask: what kind of world must exist for the appearances we see—and the formal structures we derive—make sense?

Leave a comment