This essay has been superseded by this one. Please check out the updated — and better explained! — essay instead!

Let’s start with the actual physics behind time travel. Not the science fiction version, exploring hypothetical consequences such as paradoxes that could arise if time travel were possible. And not the mathematical physics version, whereby general relativity admits closed timelike curves in which worldlines loop back to earlier times, or special relativistic observers who, traveling faster than light, might be capable of entering their own pasts.

I don’t want to discuss anything very exotic, fanciful, or conceptually mind-boggling in this post. Just the most basic physics — the definitions and topological structure needed to support a world where time travel can happen: its dynamics, its dimensionality, and the deeper assumptions we make about what kind of thing time is.

The goal here is clarity about a concept that’s simple enough to understand — at least enough to become fascinated by its possibilities — but which is rooted in categorical fallacies—such as treating temporal occurrences as though they were spatially persistent existents—that have generally gone unacknowledged.

What We See Is Not What Is

Now, we need to be clear that what we see is not what is. We see light that has travelled from all these things. Photons reach our eyes, having journeyed to us from distant objects over a nonzero period of time. So we don’t see the things as they are now, as we commonly imagine them to be. We see an image of those things — a projection of what they were like when the photons left them. The world has moved on since those photons set out. We do not directly experience the things themselves. We interact with images from the past.

Nevertheless, we do think of the world as “now” existing around us. It is a three-dimensional world, and it exists with us as time passes.

To clarify the basic physical foundation of time travel, we begin with this intuitive idea of reality.

Existence vs Occurrence

Now, there is a significant physical difference between a three-dimensional thing that exists, and a purely three-dimensional, atemporal thing. By the latter, I mean something that happens — that blinks in and out of being in an instant. An instantaneous object, like a book that flashes into and out of existence, is a purely three-dimensional thing. An existing object is something different — and our first goal is to unpack what that difference is.

So: focus on something you can see right now. Not the image you see, but the thing itself — not the light that was emitted in the past, but the distant object as it exists right now.

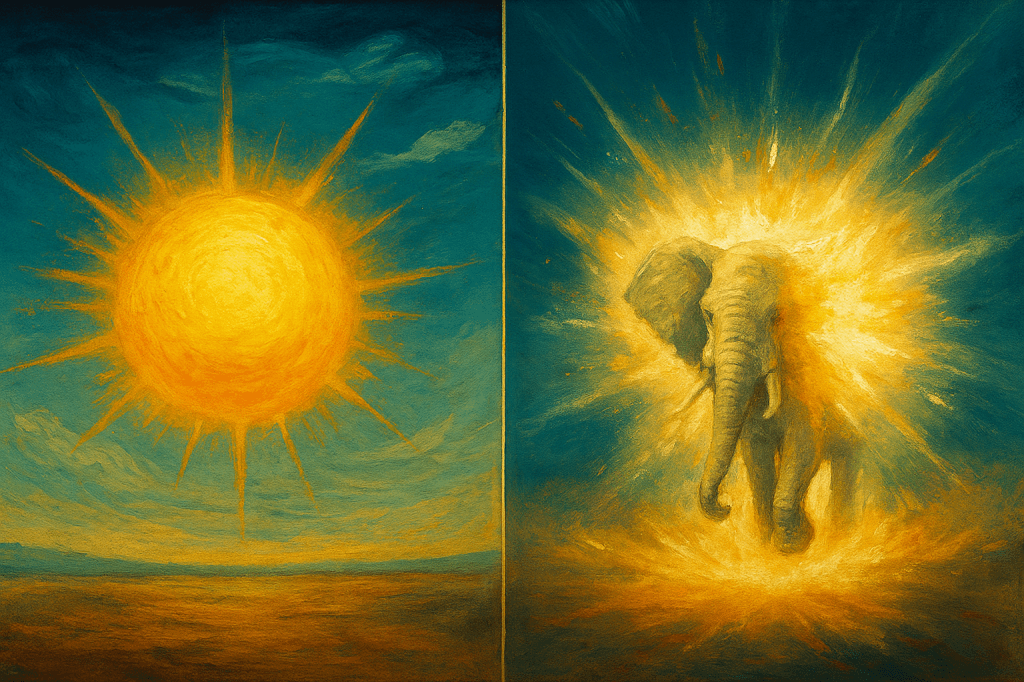

It can help to imagine the Sun. It’s eight light-minutes away from us, so when you look at the Sun, you know you are not seeing the Sun right now. You’re clearly seeing an image — one emitted eight minutes ago. The Sun right now is ontologically different.

Now, imagine that next to the Sun there is an elephant that comes in and out of existence instantaneously — an elephant of zero duration. It never “exists” at all, but in an ideal mathematical description, you imagine it as a real, three-dimensional object that happens in an instant.

That elephant does not exist in that instant. Existence is something different. It’s what the Sun is doing. The elephant happens, or occurs, in that instant.

So you see: there is a significant physical difference between an object that exists (or persists, or endures), and one that happens (or occurs). It’s a structural, categorical difference. The two belong to different ontological categories.

And great confusion arises when we collapse the two — when we speak of occurrences as existents, or vice versa.

Occurrences as Three-Dimensional Entities

Let’s unpack the dimensionality of occurrence versus existence even further.

Imagine that one day you take up meditation (if you haven’t already), and you’re sitting in a public place—say, a park—meditating. As you sit there, existing in that meditative state, someone walks up and shoots you in the head.

You die instantly. No warning, no time to react.

Now, in this scenario, the instant of your death is what we refer to in physics as an event. It’s something that occurs at a particular place and time. In this case, the event of your death—you, at the instant the bullet has passed far enough into your brain that you die—is three-dimensional. It consists of your three-dimensional body at that instant.

The question is whether it’s correct to reify that event—that occurrence or happening—as something that exists.

I would argue that it’s not. What exists in this scenario is you—a living person who happens, in one instant, to be shot; and afterwards, whose dead body continues to exist (until something is done with it). And over the course of that existence, the event of your unfortunate death occurs.

In essence: occurrences happen as things exist.

Space-Time: The Real Elephant in the Room

All right, I’ve avoided it long enough: relativity suggests there is no objective now, and that space and time are more alike than I’ve let on above. In fact, by and large, physicists do believe that time is a spatialised dimension—like space—deeply intertwined in a four-dimensional manifold we call space-time.

My claim, here and now, is that this does not alter the course of reasoning at all. Relativity theory is fully compatible with the concepts and terminology I’ve laid out above. I won’t address the relativity of simultaneity directly in this post, since my aim here is to establish the conceptual groundwork: to expose the category error involved in conflating occurrences with existents, and to clarify the basic topological structure underlying time travel scenarios (and the concept of space-time held by many physicists). A future post will address simultaneity head-on.

So, with the distinction between occurrences and existents now firmly in hand, let’s shift from the idea of existing three-dimensional objects in three-dimensional space to the concept of space-time itself.

Space-time is simply defined as the set of all events that ever occur in our universe. These “events” are not necessarily dramatic ones—like a person dying by being shot in the head—but might be as innocuous as a single point in space, a million light-years in the direction of a Cepheid variable star in the Andromeda galaxy, at a time synchronous with five minutes from now in your proper coordinate system. There may be absolutely nothing there—and how could we possibly know for a million years?—and yet something still “occurs”: an instantaneous tick of the clock at that empty point in space.

Such are the overwhelming majority of events that occur throughout space-time. But there are also more dramatic ones, like the assassination of Julius Caesar or the impact event that led to the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Space-time is the set of all such events—every instant that occurs at every point in space, throughout all of eternity. This is no controversial claim; it’s standard physics.

And so the question arises: Does it make any sense to ask whether space-time exists? Or to consider whether any particular event in space-time exists?

Consider a specific atom within that purely three-dimensional elephant we imagined earlier, next to the Sun. That atom—that point in space that occurred when the whole three-dimensional elephant occurred—is an event. Does it make any sense to describe that instantaneous atom as something that exists?

No—it’s something that occurs. And we’ve already established that occurrences are categorically different from existents. Everything that exists does so over a duration, one that can be described along a physical time dimension.

So, can we say that space-time itself “exists”?

Sure—we can say that. But if we do, we should be clear: that claim smuggles in another dimension—a dimension of existence beyond the four dimensions of space-time. In doing so, we inadvertently enter the realm of five-dimensional physics.

Existence as a Physical Dimension

When I say that existence is a physical dimension, I don’t mean it’s like space—a direction you can point toward or move through. I mean something more general, and more precise: that existence is a structural feature of physical reality, varying independently of space, and giving form to persistence. It is a basic physical condition that holds wherever and whenever anything is.

Existence is not a feature of things that happen. It is the condition that allows them to happen at all.

What does that mean?

Let’s return to the elephant—our strange, three-dimensional object that blinks into and out of being in an instant. That elephant is a flash. An event. It occurs. But it doesn’t exist. There’s no duration to it. No persistence. You couldn’t walk around it. You couldn’t even say it was—only that it happened. Once.

You might be tempted to ask: “But didn’t the elephant exist at the time it happened?” The short answer is no. That very question already collapses the category distinction established above. That phrasing already smuggles in a subtle assumption of persistence, retroactively reifying the event as something with duration or structural being. And that’s exactly the category error at stake.

Technically, the elephant occurred. To say instead that it existed at a moment risks reifying the event in our minds as a thing that endures; that event now persisting within the structure of eternity.

Now consider another elephant. One that doesn’t just flash into and out of being, but is actually there in the room with you. You could walk around it. You hear it breathe. You back away—because it’s an elephant. This elephant doesn’t just occur—it exists, present with you as time passes.

So what changed?

Not its shape. Not its mass. Not its position in space—if it stands perfectly still.

What changed is that this elephant endures. It’s there with you for more than an instant. You can say when it showed up and when it left. You can measure how long it was there—how long it existed there.

That’s what I mean when I say existence is a physical dimension. Not that it’s a direction or an axis. Not that it flows or unfolds. But that existence is measurable across time, while mere occurrence isn’t.

Existence is what the clock measures.

This isn’t abstract. It’s the world you live in. You don’t experience a flash of your own being. You live through it, moment by moment, existing. Not because you are “moving through” time, as if along some invisible line external to your being, but because you possess the ontological condition of existence. And that is what existing things do. They don’t just happen and vanish. They endure. And that’s only possible because time is a dimension—and existence is the fundamental physical structure that it measures.

This is not mysterious. It’s obvious—so obvious we often forget to notice it. But make no mistake:

We tacitly understand that the three-dimensional world around us exists. And to physically describe all the events that happen as it exists, we require four dimensions: three for space, describing the world at any instant; and one for time, the dimension along which all instants are laid out.

But that time dimension also expresses the persistence of the world’s existence.

The metrical character of that existence is reflected in the way we coordinate all the events that occur in the world as it exists, which map to a structure with well-defined, geometrical order. That structure—space-time—forms the geometrised set of events that occur in the world throughout the course of its existence. That geometry respects the metrical nature of existence as it unfolds—as the world evolves.

And once you see this everything shifts.

The space-time manifold of relativity is then seen not as reality itself—not as what exists, which is a loaded and problematic concept. Because the same logic applies when we treat space-time itself as something that exists. When we imagine that space-time exists—that all events throughout eternity truly exist—we are treating space-time as something with persistence of its own.

In order to describe that structure as physically existing—even if nothing within it ever changes, flows, or moves—even if all of eternity is imagined to remain statically frozen—we need a fifth dimension—a dimension to support the very idea that it exists. Because that supposed existence is structurally no different from the kind of existence we tacitly recognize in the three-dimensional world around us.

TL;DR: Time measures the coordinated, always-advancing existence of the three-dimensional world. Space-time is not that world—it is a structured map of all the events that occur as the world exists. The space-time metric presents not just a map of coordinated events, but encodes the metrical structure of the world’s evolving existence. And since events merely occur, not exist, space-time itself does not exist. That distinction between existence and occurrence is where everything turns. Treating space-time as if it exists requires a fifth dimension—an extra layer of structure to support the very idea of its persistence. Reifying space-time as what exists does not eliminate temporal passage; it merely displaces the unfolding of existence, hiding it in another dimension, without acknowledging the sleight-of-hand.

Meta-Now

The idea that space-time “exists” invites us—often without realizing it—to treat all events across time as somehow present. Philosophers routinely ask questions like: Does Julius Caesar’s death exist now?

But what exactly does now mean in that sentence?

It doesn’t mean “simultaneous with us,” in the physical sense. According to relativity, there’s no frame in which Caesar’s death is simultaneous with anything happening here and now. His death is in our past light cone. It cannot be “now” in any relativistic or causal sense.

And yet, if time travel is to be a literal possibility—if one could somehow arrive at that event—then there must be some sense in which it is still there to be arrived at. The event must, in some sense, exist now.

This is where the problem lies. Because that notion of “now”—one that transcends relativistic simultaneity and applies equally to all events across time—isn’t a physical one. It’s a second-order now: a meta-now layered over the entire space-time manifold we have supposed to exist.

This sense of existence is, in fact, second-order: not the kind that three-dimensional objects possess within time, but a kind of global persistence outside it.

This is what the reification of space-time sneaks into view. It’s not just a geometric model of all events—it’s treated as a thing that exists now, all at once. And that requires a fifth dimension, one in which space-time continues to persist in the way we casually imagine.

The Basic Physical Structure of Time Travel

Imagine a version of space-time like the one in Avengers: Endgame, Doctor Who, or Harry Potter—a world in which time travel is possible and specific events can be revisited, sometimes with drastic consequences.

This is a world where the grandfather paradox becomes a genuine concern: what if you go back in time and kill your grandfather before your father is conceived? In that case, your father never exists, and you are never born—so how could you have killed your grandfather?

What, exactly, is supposed to stop you?

This paradox is easy to visualize once we accept the implicit framework behind such stories: a five-dimensional ontology, in which the entirety of space-time exists, and can in principle be traversed. In this picture, the four-dimensional manifold of events isn’t just a representation of what occurs—it’s a persistent, structured object, one through which consciousness can supposedly move.

You can imagine the whole of space-time laid out like a riverbed, with consciousness flowing through it like water. Or imagine the whole river at once, with glints of awareness shimmering along its currents—each moment a localized pulse within an otherwise fixed structure.

🌀 Flux and the Fifth Dimension

This idea—that consciousness flows through space-time—only makes sense if space-time is treated as something that exists. You can’t have flux through what merely happens instantaneously. Nothing “flows” through an occurrence. Flux presupposes persistence; it presupposes a structural medium through which change can occur. That’s not just a conceptual detail—it’s a categorical distinction.

To support time travel as we imagine it in fiction, we aren’t just describing a four-dimensional structure of occurrences. We are assuming a fifth-dimensional structure: a higher-order condition that allows the space-time manifold itself to persist, in order for anything within it—consciousness, worldlines, time machines—to flow or recur.

This isn’t always made explicit, but it is always assumed.

Imagine, for example, a world like Harry Potter, where Time Turners allow a person to jump back a few hours. Suppose someone uses one to travel to a moment before their father is conceived. From that point on, their worldline no longer extends forward in the ordinary way—it branches. They travel back, re-entering an earlier region of space-time.

If they change nothing, they may simply return to their own timeline and continue onward. But if they interfere—say, by killing their grandfather—they set off a new sequence of events. Yet even that sequence unfolds within the same static structure: an existing space-time in which both the original and altered paths are embedded.

In that scenario, the person who traveled back would continue existing in this altered timeline—but the version of them from the original timeline would vanish. Their worldline would be severed at the moment of time travel, and from that point forward they would become a causally unanchored strand—a remnant of a reality that, by their own actions, no longer brought them into being.

Could such a thing happen?

Maybe. But there’s no physical evidence that the kind of five-dimensional persistence needed to make sense of that scenario exists. As far as we know, the space-time manifold is a description of what occurs, not a substrate that exists.

That’s the key: in all such stories, time travel only makes sense if we smuggle in the assumption that space-time doesn’t just occur—it persists.

Time Travel in a Fixed Space-Time

Other time travel stories—like Terminator—play out differently. Here, events are fixed. Time travel occurs, but nothing is changed. The future remains inevitable, despite the protagonists’ best efforts. Their sense of agency persists, but the outcome is already written.

But again, this sense of “already written” only makes sense if the events in space-time exist—if the whole manifold is real, fixed, and unchanging.

Even to say that the characters’ illusion of choice persists implies that something—consciousness, expectation, hope—flows through that fixed structure. That it endures. And that requires existence.

Without it, what are we left with?

A four-dimensional elephant world tube. A structure that blinks into and out of being as a whole. No flow, no illusion, no lived experience. Just all the occurrences throughout the elephant’s timeline, all manifest at once, all occurring at once, none of it enduring.

In other words: a world that does not exist, but merely happens.

Implications for Physics

So what is actually required, physically and conceptually, to support time travel?

First, the collapse of the distinction between occurrence and existence. Time travel scenarios quietly treat events—not just as things that happen—but as things that are. This conflation reifies the event structure of space-time, treating it not merely as a representation of coordinated occurrences, but as an entity with persistence of its own.

Once that move is made, the rest follows: consciousness flows, events can recur, timelines can diverge and re-converge. The notion of movement through time—of travel—makes sense only if the space-time manifold persists while consciousness or agency traces paths through it.

But that is a five-dimensional picture. A hidden one. One in which the entire space-time manifold of events exists.

And this framework—whether acknowledged or not—shapes much of how physicists and philosophers talk about relativity. It is built into countless interpretations and assumptions. Yet if we take seriously the distinction between existing and occurring—if we reject the notion that instantaneous events can persist—then the entire foundation for such time travel narratives collapses.

That collapse doesn’t just affect science fiction. It reaches deeply into physics itself.

I’ll explore those consequences in upcoming posts.

Thanks for reading. Please share your thoughts in the comments.

Leave a comment